The War Against the Wisconsin Elections Commission

Wisconsin Republicans have picked up where Trump left off.

Election Day 2020. Photo by Phil Roeder via Flickr (CC BY 2.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/legalcode

In 2007, the Wisconsin legislature established the Government Accountability Board (GAB), which was tasked with regulating state ethics and elections. The board’s establishment was a reaction to the 2001 “legislative caucus scandal” in which state legislators from both parties were discovered to have used state-paid staff members to do political work.

The board was strictly nonpartisan. It consisted of six retired judges who were nominated by the governor from a list prepared by a panel of appeals judges.

The John Doe II investigation did not go over well with powerful Republicans who, by this time, controlled all three branches of state government. Voting 4-2, in a decision written by then-justice Michael Gableman, the Wisconsin Supreme Court shut down the investigation. In his decision, Gableman referred to the subjects of the investigation as “these brave individuals.”

The Republican majority in the legislature and Walker proceeded to dismantle the GAB and replace it with the Wisconsin Election Commission (WEC). Like the GAB, the WEC had six members, but it was bipartisan rather than nonpartisan, with three members from each major party.

As with the Federal Election Commission, on which the WEC is modeled, this is a recipe for partisan gridlock. Each party is given an effective veto over every decision. As a result, the WEC has deadlocked far more than its predecessor. But the restructuring has served its purpose of preventing investigations of political leaders like John Doe II.

Enter Donald Trump and his attempt to win last November’s election he had lost. Despite deadlocks and political pressure, the WEC and GAB had managed to develop a series of recommendations for the nearly 2,000 cities, villages, and towns that actually ran the elections. Following his rejection by the voters, his campaign zeroed in on four of these, but only with respect to ballots from voters in Dane and Milwaukee Counties.

It asked the state Supreme Court to throw out many of the ballots from voters who said they were indefinitely confined. Second, it argued that all in-person absentee ballots used an invalid form and should be struck. Next, it claimed that the practice in which municipal officials added witness address information on absentee ballots made those ballots invalid. Finally, it argued that all ballots collected at two Madison events called “Democracy in the Park” should be thrown out.

The Supreme Court unanimously rejected Trump’s first point, since state law gives the voter the decision as to whether he or she is indefinitely confined because of health. After this, the justices split.

The four majority justices rejected Trump’s remaining three arguments citing the “laches” principle that lawsuits should be brought in a timely fashion. The principle is particularly applicable in elections. Once an election is run and people vote following the rules, it seems particularly unjust to change the rules and disenfranchise voters who followed the old rules.

Trump’s campaign only raised objections and challenged the voting practices after it became clear he had lost the election. To allow post-election challenges to election rules would have opened a whole new opportunity for election losers that would look ways to invalidate votes for their opponents.

When Trump retreated to Florida, his attacks on WEC policy recommendations were taken up by the state’s Republican Party. Longstanding policies suddenly became the center of controversy.

Opponents of drop boxes often claim they represent a security danger. Yet dropping a ballot into a drop box is very similar to dropping it into a public mail box. Except the drop box is more secure, even if extra measures, like video monitoring, are not used. In the drop box, for instance, the ballot need not go through a sorting process to separate it from other mail.

One criticism I find particularly disturbing is that the WEC “unlawfully suspended the use of Special Voting Deputies for nursing homes and assisted living facilities in 2020,” as WILL put it. Did the WILL staffers think through the ethical issues implicit in this criticism before making it? Residents of nursing were particularly at risk with COVID-19. Protecting their lives is something we should hope to see the WEC prioritizing.

WILL also makes two statements in its report on grants from the Center for Tech and Civic Life, which were provided to municipalities’ to upgrade their management of elections, and neither seem backed by evidence. WILL states, “We also found that private funding of election operations had a partisan bias and impact. … Private funding disproportionately benefitted Democrats.”

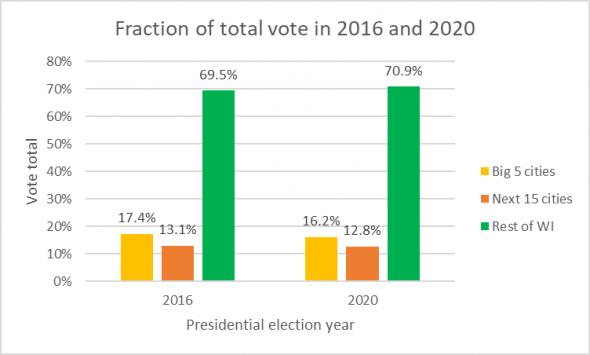

The graph below compares turnout in three groups of municipalities in the 2016 and 2020. The first group (the “Big 5”, shown in yellow) consists of Wisconsin’s five largest cities (Milwaukee, Madison, Green Bay, Racine, and Kenosha) who made a joint proposal to CTCL and received the largest funds. The middle group includes the next 15 largest cities. The green group is everyone else.

Like almost everywhere else, turnout was substantially greater in 2020 than in 2016. To neutralize this effect, I calculated each group’s share of the total in each year. Note that the Big 5’s share went down a bit while the Rest of WI went up.

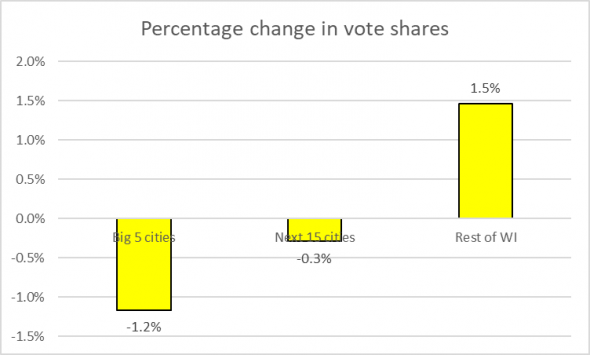

The next graph shows the change in the vote shares as a percentage of 2016 turnout.

CTCL has recently issued its form 990 report for 2020. It is massive with page after page listing the recipients of its grants. If one believes, as WILL does, that the grants were aimed at advancing the fortunes of Democrats, some of the choices would seem very strange. Minneapolis received a grant, yet a Republican has not won Minnesota since Richard Nixon in 1972. St. Louis received a grant, yet Missouri hasn’t gone to a Democratic candidate since Bill Clinton in 1996.

Why would grants intended to affect the outcome of an election be doled out in non-competitive states? But of course, WILL isn’t interested in asking this question, as it may lead them to an answer other the one they’ve already decided upon.

With almost 2,000 municipalities, all running their election systems with the advice of the WEC, Wisconsin’s election infrastructure is largely decentralized. Presumably, this is based on the theory that local people know best what makes sense in their communities. An idea that once would have been considered politically conservative in nature. Perhaps not any more.

Over a third of the towns, villages, and cities do not use voting machines to count ballots. I suspect this is a conscious decision. They have weighed the alternatives and decided that, for them, the machines don’t justify their cost.

The right-wing players, by contrast, seem to have taken the opposite path, succumbing to the belief that there is one size that fits all. Although not specifically spelled out, there seems to be an underlying belief that anything not specifically permitted in administering elections is ipso facto prohibited. That belief leads to one of WILL’s conclusions: “It is almost certain that in Wisconsin’s 2020 election the number of votes that did not comply with existing legal requirements exceeded Joe Biden’s margin of victory.”

Early on in this column, I criticized the replacement of the GAB with the WEC as a shift from a customer focused system to one focused on the comfort of politicians. Among WILL’s recommendations is replacing the present nonpartisan staff with a bipartisan one. Apparently the WEC is insufficiently political.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

Data Wonk

-

The Imperial Legislature Is Shot Down

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

Counting the Lies By Trump

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Did Politics Affect Covid Deaths?

Jun 26th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jun 26th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Republicans need to hostily take over in order to win any statewide elections.