Fusion Center Raises Questions About Privacy

Milwaukee police use it to track protestors, emails show.

Photographs taken by a Wauwatosa officer at a protest in August, 2020. Photo from the Wauwatosa Police Department.

When they were first conceived after the attacks on Sept. 11 2001, so-called fusion centers, that bring together local, state and federal law enforcement agencies, had several of goals. The idea was to improve the flow of information and intelligence throughout government agencies, which could then detect and prevent future acts of terrorism. As fusion centers diversified across the country, however, so, too, did their activities.

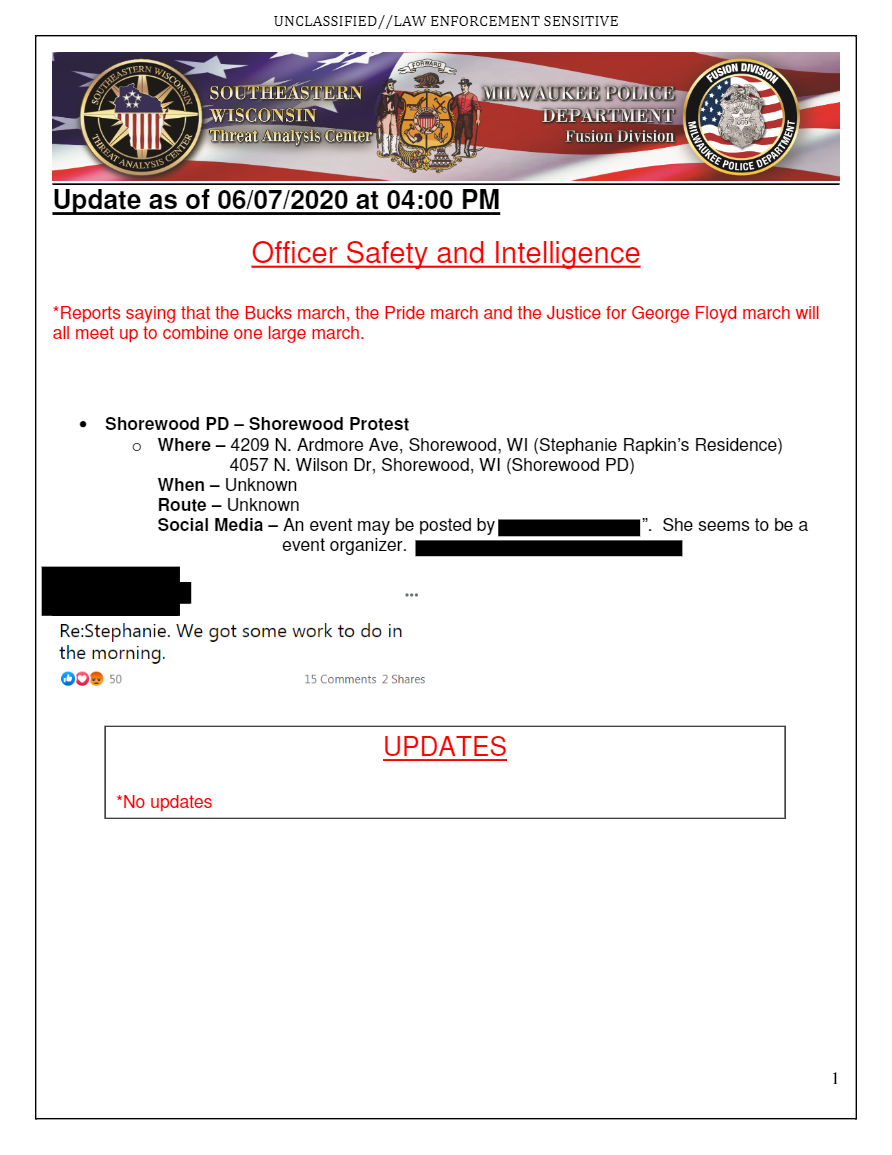

Wisconsin has two fusion centers, one in Madison and another in Milwaukee. The Milwaukee Police Department has its own fusion division as well as participating in the Southeastern Threat Analysis Center (STAC), a partnership with the FBI’s Joint Terrorism Task Force and Homeland Security. Like many other departments, MPD has begun using what was once a counter-terrorism apparatus to gather real-time information on street-level crime.

The growing capabilities of fusion centers, and their lack of transparency, worry privacy advocates. During the Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police, those concerns grew. Anonymous hackers released troves of documents dubbed “the Blue Leaks,” including internal police records. Some of those records showcased how pervasive fusion center surveillance had become.

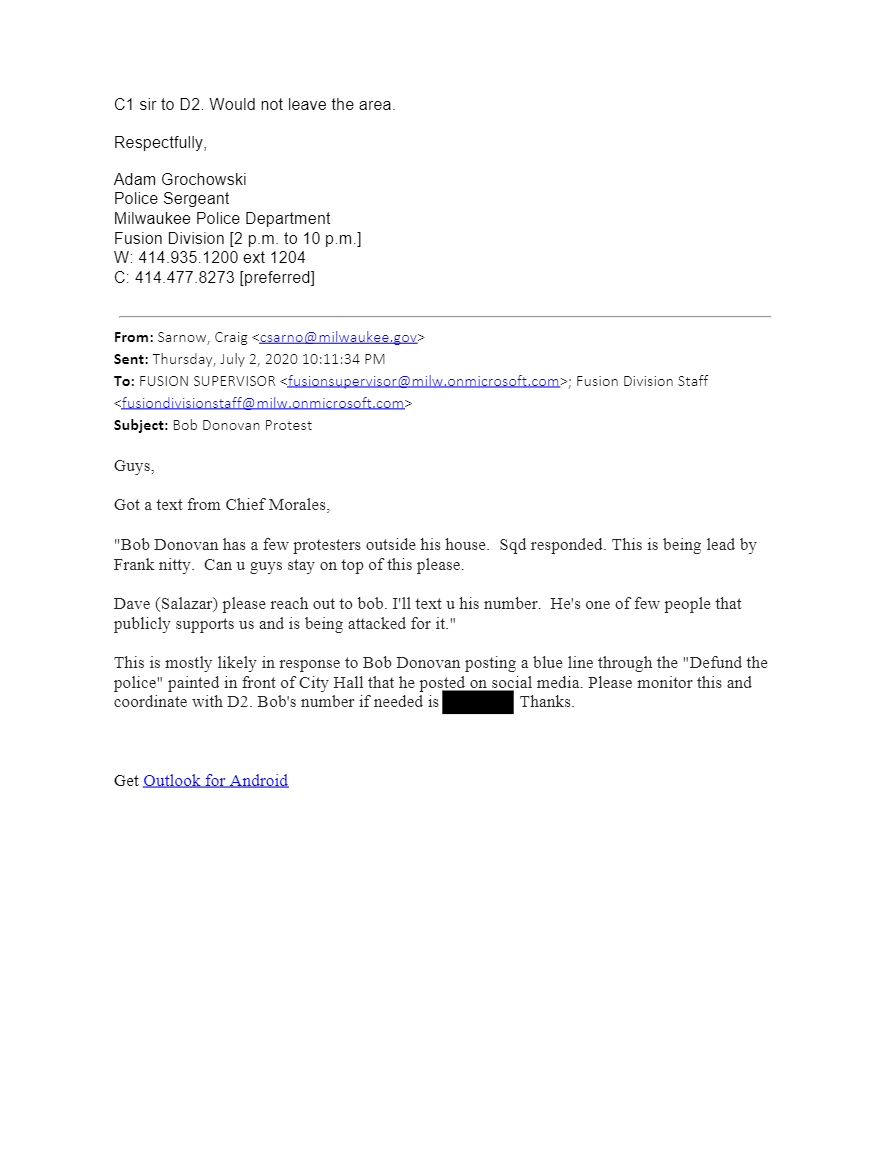

As in many other communities, questions linger in Milwaukee about how the local fusion center was used during the protests of 2020. Wisconsin Examiner has obtained numerous documents from Milwaukee’s fusion center through open records requests. Largely situational intelligence updates and emails, the records offer a glimpse into how the fusion center was utilized as protests played out around the city. One of the emails details a request to fusion by then-Milwaukee Police Chief Alfonso Morales, who is now the chief of the Fitchburg Police Department in Dane County.

In the email, sent on July 2, 2020, a fusion center supervisor relays a text message he received from Morales. “Bob Donovan has a few protesters outside his house,” the text from Morales to the supervisor states, “Sqd responded. This is being led by Frank Nitty. Can u guys stay on top of this please.” Born Frank Sensabaugh, Nitty emerged as a vocal figure during the protests that summer. The message later described Donovan as “one of few people that publicly supports us and is being attacked for it.” Donovan has since retired as an alderman, and is now running for mayor of Milwaukee. In the email, Morales reasoned that the protest was, “most likely in response to Bob Donovan posting a blue line through the ‘Defund the police’ painted in front of City Hall that he posted on social media. Please monitor this and coordinate with D2.”

The day after the email was sent, fusion center personnel continued gathering background information on the arrested woman, Bethany Crevensten. Meanwhile, unbeknownst to either of them, both Crevensten and Nitty had also been placed on a list of nearly 200 people who police felt were involved in protesting. Originally created by the Wauwatosa Police Department, the list was shared with numerous law enforcement agencies including MPD. Emails sent within a Google email group police used to share information last year also specifically mentioned Crevensten’s involvement in other protests in the area. After holding a different protest outside an individual’s home in early June, Crevensten said she was visited by officers at her home. “They showed up to my house and told me the whole city knows,” recalled Crevensten.

Morales didn’t respond to a request for comment for this story. His email to fusion raises a couple of questions about how fusion was used. Although protests were ongoing on a daily basis throughout the city, the former chief instructed MPD’s intelligence hub to pay particular attention to “a few protesters” outside the home of a local politician who was a staunch pro-police voice in City Hall. A month prior, Morales himself compared the growing protests and criticisms of law enforcement to Christ’s crucifixion. Morales also downplayed concerns when protesters began receiving curfew tickets from fusion’s Virtual Investigations Unit, which had been monitoring social media videos. Fusion personnel continued gathering information about those few demonstrators outside of Donovan’s, who were continually monitored by law enforcement for months afterward.

Many of the fusion center’s intelligence reports relied on social media posts. From event pages organized on Facebook to various posts ranging from potential threats of violence, reports describing people open-carrying weapons, and notes about protesters using Signal and Discord chat software to communicate securely with one another. Some of the reports specifically mentioned protest events attended by figures like Nitty, local grassroots community organizer Vaun Mayes, and others. Fusion was disseminating information about protests not only about Milwaukee, but also other counties under its jurisdiction.

Spread among those bullet points were also occasional notifications of routine criminal activity, like carjackings or Shotspotter alerts. The information that came in was, at times, imperfect. One situational report from early June 2020 stated that “protesters set a Racine police officer’s house on fire.” In fact, arsonists had set fire to a Community Oriented Policing (COP) house, which is part of a localized policing strategy funded by the Justice Department. Several people were arrested and charged with the fire, which damaged the first floor of the COP house. The Racine Police Department confirmed to Wisconsin Examiner that officers staff the COP house but do not live in it. Other reports mentioned the alleged throwing of a Molotov cocktail by protesters, though the object which was thrown was not recovered by officers. In October 2020, MPD walked back its claims that a Molotov had been thrown.

Randy Shrewsberry, a former police officer who has worked with several departments around the country and is the founder and current executive director of the Institute for Criminal Justice Training Reform, says the public has a stake in how fusion centers are used. “Twenty years after the Patriot Act and the eventual creation of fusion centers across America,” Shrewsberry told Wisconsin Examiner, “citizens are owed explanations of what role these federal agencies are taking in non-terrorism matters — or how we’re stretching the term ‘terrorism.’ Without clear lines, local agencies may be tempted to utilize their fusion center resources and support beyond the scope of anti-terrorism efforts, spilling over in areas such as constitutionally protected protests.”

How should fusion centers be used during protests? was originally published by the Wisconsin Examiner.