Can State Fix Problems Underlying the Labor Shortage?

Evers administration putting $130 million into addressing issues contributing to labor shortage.

Help Wanted. Photo by Andreas Klinke Johannsen (CC BY-SA 2.0)

At the age of 37, Nadia Spencer decided to train for a new job.

Spencer qualified as a certified nursing assistant in 2009 and worked in a series of health care jobs, in nursing homes, group homes, and more recently providing coaching for people with disabilities to help them in their work. But after being let go in March, she decided that she needed to leave the health care profession.

Late in the summer, Spencer started a training program to be a freight broker, helping to dispatch truck shipments. The job would allow her to work from home in Madison. That would be an advantage, she said; some of the jobs she has considered had shifts that conflicted with the available child care hours for her 2-year-old daughter and 8-year-old son.

A care center for her daughter that closed at 5 p.m. or later before the COVID-19 pandemic was now closing at 4:30 p.m. And with her son’s school day starting at 8 a.m., and before-school child care not opening until after 7 a.m., she was unable to make a 7 a.m. start time at one prospective job.

Even without a job, she would need child care to make it possible to look for work. But “if you’re not working, you can’t get child care” under state programs that provide child care subsidies for low-income workers, Spencer said during an interview in early August. “I still need the time to look for a job — I’m overwhelmed.”

There are lots of Nadias around Wisconsin — people trying to figure out how to make their way in an economy that is working fine for some and not so well for many others. For some, like her, the problem is juggling work schedules and child care. For others, it might be figuring out how to get to work if a car is unreliable and there’s no public transportation. For others, it can be whether their skills match the jobs that come their way.

Their challenge is connecting, in all the complexity of their personal lives, with work that needs doing. It’s a challenge for policymakers, too.

At the same time, however, “we are hearing from employers that they have vacancies they can’t fill, that there’s a worker shortage,” Pechacek said. “And we’re hearing from job seekers that they are having a hard time finding employment that matches their skills.”

The mismatch preceded the COVID-19 pandemic, but the pandemic has made it worse. In his original draft 2021-2023 budget, Gov. Tony Evers had proposed $29 million for several programs for job training and related initiatives to close those gaps, with particular attention to the pandemic’s fallout. For the most part the governor’s workforce proposals were left on the cutting-room floor when the Republican majority on the Legislature’s Joint Finance Committee finished writing its own version of the budget, which Evers signed in July.

As the committee voted in June along party lines to remove the original proposals, Rep. Mark Born (R-Beaver Dam) dismissed them as “welfare.” If they were important enough to preserve, he added, “then use the federal money.”

Now, the Evers administration is doing exactly that.

Navigators and coaches

This summer, the governor announced a $130 million package of grants to begin addressing long-festering gaps in the state between people and jobs, paid for by some of the $2.5 billion that Wisconsin has received under the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) enacted in March.

The announcement included $30 million for projects spearheaded by DWD to help people overcome barriers to joining or returning to the workforce.

“We know that individuals often have a hard time reentering the workforce due to reasons that have nothing to do with the actual job itself — but due to other barriers such as childcare, transportation, housing, mental health care,” Pechacek said at the July meeting, which was held to outline details of the administration’s workforce grants package.

Communities may have programs and services that address some of those needs, she added. “But they’re often hard to find and hard to access if you don’t know exactly where to look.”

The Worker Connection Program will supply “navigators” — career coaches who work with job-seekers to pull together the resources they might need, such as social services or job training programs. “These navigators are going to connect the dots between all of the state programs, the community programs, the nonprofit programs, and make sure that these folks are able to overcome any type of barrier that they have so that they can be successful and re-engaged in the workforce,” Pechacek said.

The $10 million will fund pilot programs in two regions of the state with 40 people serving as navigators. The project, still in development, is modeled after a similar program from Ohio.

Transitional jobs

The second DWD project is a $20 million transitional jobs program to provide subsidized employment with training that bridges people to a stable, full-time, unsubsidized job. That was not in Evers’ original budget, but it is modeled on a concept that has been in use already in Wisconsin as part of the state’s aid to needy families administered by the Wisconsin Department of Children and Families (DCF).

The new ARPA-funded transitional jobs program, housed at DWD, is called the Worker Advancement Initiative. The program is to provide temporarily subsidized jobs to about 2,000 people, either chronically unemployed since before the pandemic, or who lost jobs because of the pandemic and have been unable to find work since then. Funds will be used for training in specific job skills as well as broader workplace skills; they can also be used to help address employment barriers such as child care, housing and transportation.

The money is being funneled through the state’s 11 workforce development boards, regional agencies that also distribute federal worker training funds in consultation with employers, technical colleges and labor organizations.

Josh Morby, a spokesperson for the Wisconsin Workforce Development Association, says that the regional workforce boards bring to that project experience going back into the 1990s, when they were established to direct federal funds for worker training and related purposes. The boards also include, by law, employer representation and are very familiar with the growing difficulty many employers were having in hiring workers even before the pandemic.

“They’re the ones that have relationships with local employers,” Morby says, and interact with job-seekers as well. The workforce board participants also understand that “there are several factors that contribute to the labor shortage in Wisconsin,” he adds, with child care and transportation being just two. “Many of these are not quick fixes.”

Community and regional hiring obstacles

While the first two programs are operating out of DWD, the remaining $100 million, the bulk of the package, is going to a project with a much bigger scope, run primarily by the Wisconsin Economic Development Corp. (WEDC).

The Workforce Innovation Grants program is a nine-figure bet on the administration’s fundamental vision of what lies at the heart of the workforce shortage — not just the COVID-19 pandemic, but a much longer, festering mismatch between jobs and the jobless that has dogged employers, policymakers, whole communities and workers themselves for more than a decade.

“There’s a reason we’re doing this on a regional or local basis,” Missy Hughes, the WEDC’s secretary and CEO, says in an interview. “It’s because each of the regions and communities in Wisconsin have different challenges when it comes to workforce.”

It isn’t just happenstance that the innovation grants are being administered by WEDC. The project shows how the agency’s priorities and focus have sharply expanded under the Evers administration and Hughes.

From its creation early in the administration of Scott Walker, WEDC defined economic development in traditional terms: marketing the state to employers and using tools such as targeted tax relief and government grants to encourage in-state businesses to stay and out-of-state businesses to relocate here.

Those are still in the WEDC’s tool box, but over the last two years, Hughes and the Evers administration have broadened the agency’s agenda. In an April 2021 report, Wisconsin Tomorrow 2021, Hughes spelled it out, building on premises that she has been articulating since taking office in October 2019 and with increasing emphasis since the COVID-19 pandemic.

From economic development to economic well-being

To have effective economic development, Hughes has often suggested, the state can’t just respond to the interests and demands of employers, but must also address the needs of its communities and people. The April report calls the objective “economic well-being” — for individuals, for communities and for the state as a whole.

COVID-19 “revealed vulnerabilities and gaps in our systems that became chasms during the pandemic,” Hughes wrote in the report. “An economy of the future must be powered by Wisconsinites, but must also serve Wisconsinites.”

The Workforce Innovation Grant program is an attempt to put those principles into operation. “Just having a job isn’t enough,” Hughes says. “To fully participate in the economy and have individual prosperity, you need to also have the community that you’re living in, and the infrastructure in your community.”

She includes among those infrastructure needs broadband internet access, child care, stable housing and transportation networks, along with adequate education and health care systems. The pandemic, she says, showed that “there’s all these pieces of the puzzle that need to come together” so that the economy can thrive and so that all can participate in it. “We need to provide resources, so that we can then have folks able to get to their work and stay at their work.”

The deadline for the first round of applications for the grants, which can be for up to $10 million a piece, comes up in about two weeks, on Oct. 25, and WEDC wants to see applications that reflect broader teamwork within a community or region.

“It’s important to us that the solutions come from the communities and represent collaborations among different entities in the communities — whether it’s not-for-profits, or businesses or governmental organizations,” Hughes says. “We want everybody coming together [and] saying, ‘This is our priority, this is the thing that’s most important for our region, and the thing we want to focus on.’”

Riding for cheese

On the last Friday in September, Pechacek, the DWD secretary-designee, rode over to the tiny village of Reeseville in Dodge County to see what one employer has done to make it easier to find workers.

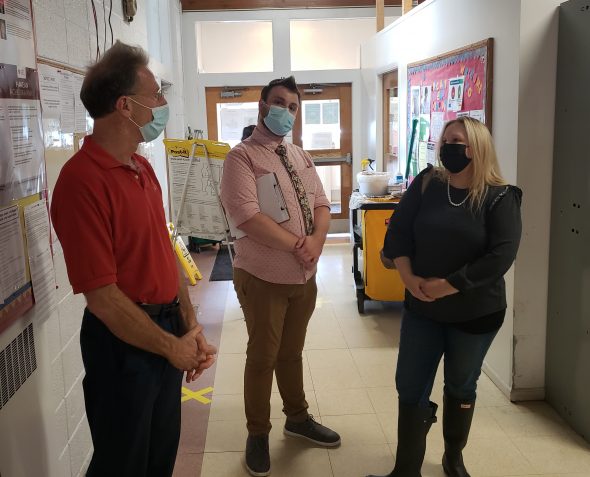

Paul Scharfman, president of Specialty Cheese in Reeseville, speaks with DWD Secretary-designee Amy Pechacek, during her visit to the company in September. Between them is Harley Lemkuil, Specialty Cheese training manager. Photo by Erik Gunn/Wisconsin Examiner.

Specialty Cheese Co. in Reeseville is in a shuttered high school that Paul Scharfman, the owner and president, bought for his growing businesses in 2003. “We have employees who went to school here,” Scharfman, whose office occupies the old principal’s office, told Pechacek and a handful of others touring the plant.

The company’s products include paneer, a white cheese favored in the cooking of India; in 2018, Specialty’s paneer was named world champion in its category in international competition. Specialty also produces a baked cheese snack food along with cheeses of the kind used in Mexican and other Latin American cooking.

Employment has been increasing over the last decade; the staff currently numbers about 250 people. There are shifts around the clock, starting Sunday nights and ending Saturday morning, when the plant shuts down for the weekend.

With Reeseville’s population below 700, the factory has had to look far beyond the borders of the village and even the county to hire workers. Three years ago, Specialty Cheese launched a ride-sharing program, hiring a driver to provide daily shuttle service driving employees to and from work.

Today the service has grown to seven drivers, each taking a fixed route that stops at the home of every employee who needs a ride. Some workers come from Beaver Dam, the nearest municipality, others ride further from Waupun, Randolph or other communities. Currently the farthest route goes to Fond du Lac, 50 miles away.

Drivers are employees of Specialty Cheese; some have been production employees serving as drivers at the start and end of their shift, but mostly they have been hired just to do the driving. Riders are charged $4 a ride or $8 a day to help offset the cost of the program, which Scharfman says is about $20 a day per employee.

“But now I have a workforce,” he says. “What’s it worth to you to have a job opening filled?”

Flor Vanessa Sanchez schedules drivers as the company’s transportation coordinator. The current passenger load is about 70 people — a little less than one-third of the workforce. And Harley Lemkuil, now the training manager and formerly the transportation coordinator, says ride-share participants account for the bulk of new hires in recent months, many of whom find their way to the business after hearing about it from others. “A lot of people choose to work here because of the ride-share program,” Lemkuil says.

While proud of the ride-share program, Scharfman believes the company owes its success in boosting employment as well as retention to more than providing workers with transportation. He credits the ethic of “emotional intelligence” that the company has put at the center of its personnel management practices for nearly a decade. “Feelings matter. Compassion works,” Scharfman says. In dealing with employees, “that person is first a person, and second a worker.”

He also contends that the state’s rural communities still harbor potential, including potential workers who want jobs but who have been stymied by the same recurring challenges like childcare, transportation and housing costs. “We can revitalize rural Wisconsin,” Scharfman says.

Working two jobs, hoping for one

Two months after her earlier interview, Nadia Spencer spoke last week about her job search.

She completed training to be a freight broker, and last week she took the required final exam for the course.

But Spencer also had to take a job to ensure she could keep her 2-year-old daughter in child care. “They only pay if you’re working,” she said. “Full-time school is not recognized” under the child care subsidy program — something she would like to see changed. “School is good,” she said.

In the meantime, because of a bus driver shortage, her son’s school shifted its start time to just before 9 a.m.

So Spencer has accepted a customer service position for a medical supply business. The job requires her to go to the company’s offices. But her new employer has allowed her to shift her start time 15 minutes later and to leave work 30 minutes early because of the child care hours — which are also restricted because child care centers can’t find enough workers.

So, for now, Spencer will do that work while juggling her children’s school and child care schedules, and doing the freight-broker work as a side job on her off hours, “and then try to get as much experience as I can,” she says. “It takes a long time to be a good broker.”

Matching workers with the right jobs was originally published by the Wisconsin Examiner.

Business needs to pay higher wages, better benefits, and stop treating workers badly.