Purdue Renames Dorms to Honor Mequon Sisters

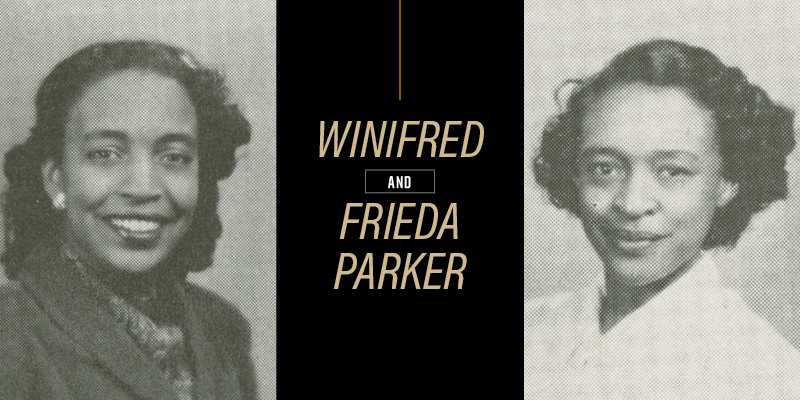

Frieda Parker Hall and Winifred Parker Hall honor students who integrated dorms in 1947.

Frieda Parker Jefferson and Winifred Parker White were sisters whose families were among the first Black residents of the City of Mequon, settling between 1966 and 1968. Yet this was not their first move to integrate a community: two decades previously, as teenage students at Purdue University, the inseparable pair opened the doors of the school’s dormitories to African Americans in an early civil rights success, officially commemorated last week.

Their admission to Barnes Dormitory followed a protracted struggle with university administration that involved community activism, and, ultimately, the governor’s intervention in their cause.

The sisters were posthumously recognized on June 11th when the trustees of Purdue University voted to rename two adjacent dormitories as Frieda Parker Hall and Winifred Parker Hall. They are the first buildings on campus to be named after black alumnae.

Story Little Known — Even to Family

Frieda Parker Jefferson, wearing her Purdue jersey while taking a walk on the grounds of Homestead High School in Mequon. Photo taken May 2020 by Ralph Jefferson.

The remarkable story of how these two women from the class of 1950 were able to break a racial housing barrier at Purdue was little known, even within the family. Frieda’s son Ralph Jefferson III (Purdue ’80), tells Urban Milwaukee: “Growing up, my mother and aunt really didn’t talk about it. My mother did say that there was an issue regarding blacks living in the dormitories, and that my grandfather became involved in a movement to get it resolved.”

Announcing the name change, Provost Jay Akridge said, “It’s one of those stories of persistence and path-breaking action and really opening up doors for so many others — both women and women of color.”

Frieda Parker was born on September 9th, 1928, with her sister Winifred following a mere ten months later. Their parents, Frieda Alice Campbell Parker and Frederick Allen Parker, were both college graduates. A collegiate education and involvement in the community at large was an imperative for their children.

The girls attended the segregated Crispus Attucks High School in Indianapolis, where their father was the math instructor. The entire student body and faculty was Black. Frieda graduated second in her class in January 1946. Winifred graduated as first in her class the following May.

At Purdue: Excluded from Dorms and Student life

According to Frieda Jefferson’s 2020 obituary:

In the Fall of 1946, Frieda and her younger sister Winifred enrolled in Purdue University. Frieda and Winifred were the first two African-Americans to integrate the residence halls at Purdue. This was not an easy exercise. At the time, African Americans were not permitted to live in West Lafayette, Indiana, where the Purdue Campus was located; they were all required to live some distance away in the Black section of segregated Lafayette, Indiana. This is despite the fact that the rules of the University, a state supported public research institution, required all freshman women to live on campus.

Frieda and Winifred, supported by their parents, insisted that Purdue University abide by its own rules because, despite their race, they were nonetheless a tax-paying family in the State of Indiana. Their residence request was denied by the University administration so the family organized Black community leaders and appealed the decision to Governor Ralph Gates, who eventually yielded to their unwavering persistence and directed the University to change its policies regarding segregated housing. At the time, only twenty-five Black students were enrolled in the University, which then had a student body in excess of five thousand.

The Parker sisters rightly felt that they were excluded from full enjoyment of the university experience due to the housing prohibition. This forced them to walk, or take the bus to their housing, and to miss many campus and extracurricular activities available to others.

Frieda Parker Hall and Winifred Parker Hall. Photo courtesy of Purdue University. Photo courtesy of Purdue University.

Frieda recollected her father’s correspondence, and its faultless logic: “He made it well known that Purdue was a land-grant school supported by state taxes, and his taxes supported the school just like everyone else’s, so why couldn’t his children live on campus?” she said. “The fact that Blacks were not allowed in the dorms was a policy that had been set up in the housing office at Purdue. It was not a law.”

Frieda Jefferson, who died last July at 91, taught for many years at James Madison High School. She was also one of the organizers of the Milwaukee Teachers’ Education Association, which represents Milwaukee Public School educators. Both her son Ralph III, who works for Catalyst Financial Group, and his brother Brian, the former chairman of Cobalt Energy Group, are graduates of Purdue.

Brian Jefferson drove to West Lafayette last week to attend the trustee’s unanimous vote to rename the dorms, and wrote on Facebook:

Just got home from West Lafayette – home of Purdue University; my alma mater. Never thought I would witness the board of trustees unanimously agreeing to name two dorms after my mother and aunt posthumously. I am blessed to have had these two women in my life who made a difference. What an example they set for my family.

Winifred White, who died in 2003, was trained as a microbiologist, but later received a degree in social work, and spent years coordinating school-to-work programs for MATC. She remained active in civil rights issues along with her husband, dentist Walter Hiawatha White, Sr.

Daughter Winifred White Neisser graduated from Mequon’s Homestead High School in 1970, and graduated from Harvard University in 1974. She is a resident of Los Angeles and served as a senior vice president for movies and miniseries for Sony Corporation.

In a statement for Urban Milwaukee, she writes:

It is so gratifying to have Purdue recognize my mother and my Aunt Frieda for their perseverance in getting access to a good education. They recognized, when others did not, that a quality education includes learning from people whose backgrounds and perspectives may differ from your own. Neither my mother nor my aunt sought this kind of recognition. … Their determination, positive attitudes and good humor broke down many barriers in their lives. I hope this acknowledgement is an inspiration to young people to not give up or be afraid to reach beyond what is comfortable.

Walter H. White, Jr. is a former Commissioner of Securities for the State of Wisconsin, and is now an attorney in London. Thanks to his parents’ involvement with the NAACP and the Milwaukee Urban League, young Walter’s childhood memories include meeting Thurgood Marshall, Fannie Lou Hamer and Benjamin Mays, along with other figures in the civil rights movement.

According to a 2015 article in the Wisconsin Lawyer:

When White was 6 years old, he got the chance to meet Martin Luther King Jr., backstage at a dinner event where King was the main speaker. ‘He sat me on his lap,’ White recalls, ‘while he was talking to the (then) Milwaukee Journal.

Their sister Adrienne White-Faines is a healthcare executive in Chicago. Like her grandfather she is an Amherst graduate. Brother Charles White, also a college graduate, lives in Milwaukee, and formerly worked in Chicago.

Sisters Were Mequon Pioneers

The Parker sisters and their families were not the first black residents of Mequon. That distinction belongs to Henry Aaron, then a star with the Milwaukee Braves, who moved there with his family in 1959. The Whites moved to Mequon in June 1966, one year after that city became the first Wisconsin community outside of Milwaukee County to enact an open housing ordinance, an important consideration for the family.

Peter Raymond, a Homestead High School contemporary of the families, wrote a paper in 1992 for his studies at UW-Milwaukee recounting the history of integration in Mequon from 1959-1969. The White and Jefferson families were central figures:

[Winifred White] and her children saw Claudia Baldwin [daughter of early black residents] in the Homestead High School Marching Band during the 1965 downtown Christmas Parade in Milwaukee. ‘Not only was she the only black person in the band, she was in front of the band, leading it!’ That impressed the entire family.

It also sealed the family’s determination to make Mequon their home in time for the next school year.

Twenty-four months later, the Jeffersons moved to Mequon, ending the “only two years the sisters would ever be more than a short distance apart,” Ralph Jefferson said Sunday.

The sisters were particularly close, speaking by telephone the first thing each morning and the last thing before bed at night.

Father “Fails” Literacy Test

Frederick Parker went to vote in Indiana as a young man. In order to do so, the college graduate was required to pass a literacy test. In the Wisconsin Lawyer story, Walter White recounts that his grandfather easily passed the test, given in English.

The voting official then insisted Parker pass the test in French — a language he did not know. But, since he did know Latin, he was able to muddle through, again successfully. Finally, he was told to take the test in Chinese and failed. He was turned away from the polls. “They did not want him to vote,” says Vernetta Nelson Jefferson, Ralph’s wife. Family members remain active in supporting voting rights generations later.

Dorms had Previously Been Named for School Mascot

The dorms that honor the legacy of the pioneering Parker sisters had previously been known as Griffin Hall North and Griffin Hall South, named after the mythological creature that serves as Purdue’s mascot and is represented on the university’s seal.

According to Mythology.net:

A griffin (or gryphon) is a chimeric creature, part eagle and part lion. With incredible strength, unfailing protective instincts, and a zero-tolerance policy against evil, it is the superhero of mythological creatures.

Video

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

Plenty of Horne

-

Villa Terrace Will Host 100 Events For 100th Anniversary, Charts Vision For Future

Apr 6th, 2024 by Michael Horne

Apr 6th, 2024 by Michael Horne

-

Notables Attend City Birthday Party

Jan 27th, 2024 by Michael Horne

Jan 27th, 2024 by Michael Horne

-

Will There Be a City Attorney Race?

Nov 21st, 2023 by Michael Horne

Nov 21st, 2023 by Michael Horne