The Science on COVID-19 and Schools

When are in-person classes safe and when can they help disease surge? That depends.

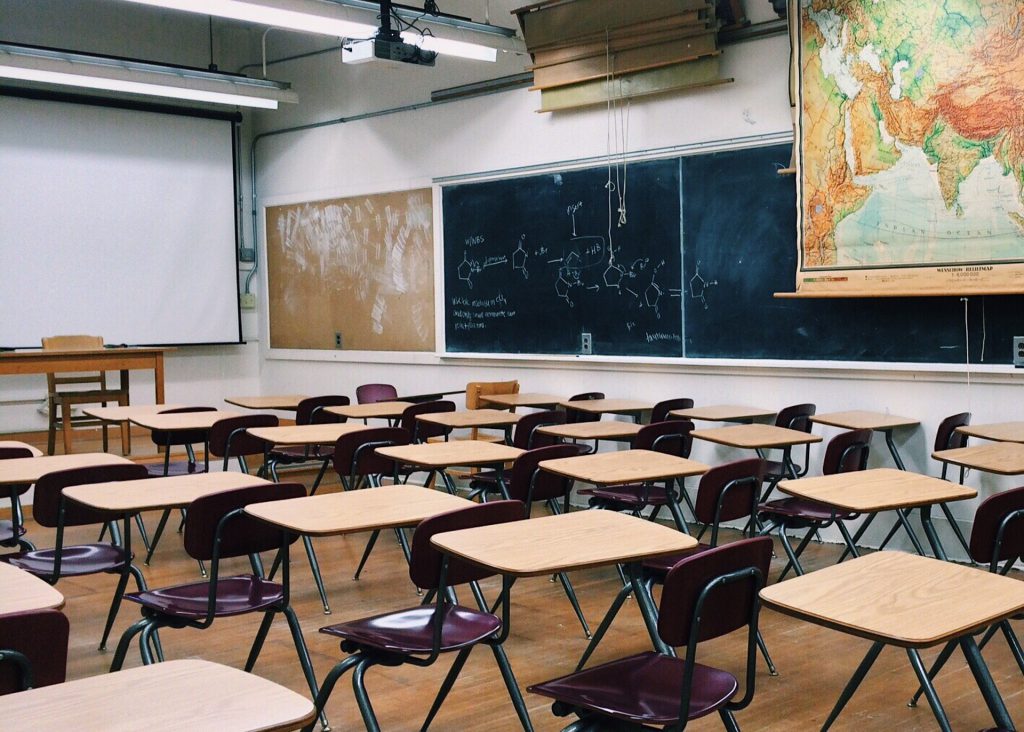

As a new semester gets underway, conflicts continue over whether schools can safely return to in-person instruction as COVID-19 remains widespread.

But in the face of assertive claims from lawmakers and others that face-to-face teaching is safe in the pandemic, the scientific evidence and the perspective of some epidemiologists and public health practitioners is much more complex and cautious.

The pandemic has brought widespread disruption to public health and to the economy — killing more than 5,000 Wisconsin residents and more than 370,000 Americans, shuttering businesses and destroying millions of jobs. It has also disrupted schooling, and with it the lives of both educators and families.

The dilemma over school in the pandemic has been fraught with excruciating choices. And it has become polarizing.

Claims of safety

After schools went virtual in March on the order of Gov. Tony Evers and stayed that way for the rest of the spring semester, Republican lawmakers by early summer were insisting on in-school instruction for the fall. Teachers unions urged caution because of the risk to teachers exposed to the virus, as well as the challenges of maintaining social distancing in the classroom and ensuring that students and families would comply with mask requirements.

The challenges for schools, teachers and parents alike persisted with the new school year. Many districts opted to continue online schooling — or quickly shifted back to virtual education in response to a surge of confirmed COVID-19 cases.

Now the dispute has revved up again. The COVID relief bill that Assembly Republicans passed Wednesday, Jan. 6, would require school districts moving to virtual education to get the approval of a two-thirds majority of the school board — and take a new vote every 14 days. (Proposals floated in December to impose financial penalties on districts for teaching virtually were left out of the bill.)

Both agencies were sued by the right-wing Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty (WILL), which has also challenged repeated emergency declarations due to the pandemic and the statewide mask order.

Lawmakers and others who are pushing to require in-person schooling claim that the danger is minimal. “The scientific evidence has become increasingly clear that it is safe to reopen schools, yet many districts still don’t offer in-person instruction,” WILL states in a December blog post that endorsed Republican proposals to punish school districts that teach virtually.

The entry’s only citation backing up that assertion is itself a blog post — not a scientific journal article.

But a Wisconsin Examiner review of statements from medical organizations and recent papers analyzing the safety of in-person classes, as well as interviews with public health experts and epidemiologists, suggests that casual claims of a broad scientific consensus on the safety of in-person schooling are at best premature.

To the extent that there is any agreement, it comes with strong conditions: Where students and teachers meet face to face, schools and the people in them must observe rigorous measures to control the spread of the coronavirus, according to public health specialists. Those include masks, regular sanitizing and handwashing, frequent testing, isolation and quarantine for people infected or exposed, and swift and thorough contact tracing.

‘Astonishing’ rate of infection in English children

The idea that children are less likely to transmit the coronavirus is widespread.

“There is a fair amount of data out there now that indicates younger children are less of a transmitter of this disease,” Evers said during a Department of Health Services (DHS) media briefing Dec. 10. The governor repeated the assertion about two weeks later: “The evidence does tend to show, I believe, from what I’ve heard experts say, is that young people don’t transmit the disease at the same rate that other folks do,” the told reporters during a Dec. 22 DHS briefing.

A collection of studies calls such blanket assurances into question, however.

“In England, random testing of the population shows children and teenagers are now the most infected age groups in the country,” Hyde, the Australian epidemiologist, told Wisconsin Examiner in an email interview in late December. “An astonishing 1 in 48 teenagers and 1 in 58 children tested positive in the most recent round of testing.

England went through a nationwide partial lockdown from Nov. 13 to Dec. 3, during which schools remained open. “Importantly, the data show that cases in adults declined” during that time period, “but cases in children increased,” Hyde says. “This dispels any notion that children are seldom infected, and suggests a major role for schools in transmission.”

Theresa Chapple, an epidemiologist in the Washington, D.C., area, has been consulted by 27 school districts around the country on how they might safely operate during the pandemic.

In analyzing the risk of in-person schooling, “I think that there is still a gap in the data,” Chapple says.

For example, most school districts where children attend in person don’t appear to be broadly testing either students or adults — teachers, staff or others — for the coronavirus. Instead, testing is targeted at people who show symptoms from the virus or who have been exposed to people who have tested positive.

“So we still don’t have the true number” of people who might have the virus, Chapple says. “We know that there’s asymptomatic spread, and that’s not being reflected in our numbers.”

Dangerous generalizations

She also sees danger in generalizing about the larger school population, whether students or the adults who are teachers and other staff members.

Even where there has been some in-person teaching, students are “probably not” in the classroom five days a week, Chapple says, while adults, such as food-service workers, are more likely to be there every day. In comparing their rates of infection, their actual exposure might be quite different — “so we continue to compare things that are not comparable.”

The school environment can also vary widely. If schools aren’t well ventilated, the level of risk for exposure to the virus could be much greater than at a school with the resources to upgrade its ventilation system.

“We can’t learn from mixed data like that without parsing it out,” Chapple says. “If we talk about schools as one thing, without realizing that there are differences across schools, then we’re making a really big assumption that can be dangerous.”

The school districts that have sought her advice have differed one from another — both in their specific circumstances and in their objectives.

“There were some that said, ‘We have to open up, and [need to] figure out how to do it face-to-face’ — how to do it safer,” Chapple says. “It wasn’t that I was always brought in to help determine if it’s a good idea or not. Sometimes I was brought in and the determination had already been made.”

Dane County: Safer than before?

In mid-December, Public Health Madison & Dane County (PHMDC) issued new guidelines related to school operations. A Wisconsin Supreme Court injunction in September barred the health department from ordering schools to close. Even so, the Dec. 14 order offered stronger support and encouragement than previously for schools to resume in-person classes — as long as they employ strong infection control measures.

In-person schooling is “a less risky environment than previously thought earlier in the year,” says Katarina Grande, a public health supervisor and the department’s data team leader. PHMDC relied on nationally collected data and assessments on schools and COVID-19 that showed “a convergence of evidence suggesting that it’s safer.”

Safer doesn’t mean completely safe, however, and if schools are open, the new guidelines require them to observe practices aimed at continuing to avoid spreading the virus: extensive hygiene and cleaning routines, wearing face coverings indoors for everyone 5 or older and strict physical distancing policies keeping people 6 feet apart. The guidelines also require keeping students and staff in small groups of the same people, minimizing situations where different groups will mix.

“Those sorts of general guidance that have been in place for much of the pandemic are really critically important in the school environment, too,” Grande says.

While the Madison and Dane County guidelines offer more latitude, the Madison Metro School District announced on Friday (Jan. 8) that classes will remain virtual when the school year’s third quarter starts Jan. 25.

“Throughout the first two quarters, district staff have reviewed health and operational metrics, while making our buildings ready for in-person instruction with rigorous mitigation strategies and planned responses for confirmed cases,” according to a district statement. “After weeks of careful analysis, consultation with health experts, and close consideration of a recent decline in local cases, the metrics still do not support a safe return to our school buildings at this time.”

Chapple and Hyde agree that if schools hold classes in person, they must pay strict attention to safety measures.

“At a minimum, that means the use of face masks by staff and students, increasing ventilation and reducing class sizes,” says Hyde. Guidelines from the Harvard School of Public Health reiterate those precautions.

Missing context

People arguing that schools must return to in-person classes often cite the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), which in July posted a guidance statement that declares, in boldface type, that “the AAP strongly advocates that all policy considerations for school COVID-19 plans should start with a goal of having students physically present in school.”

But often left out, or mentioned mostly in passing, are the lengthy qualifications in the physicians’ organization statement that come before those words.

To ensure school safety, communities must “take all necessary measures to limit the spread broadly of SARS-CoV-2 throughout the community,” according to the association. “Community-wide approaches to mitigation are needed for schools to open and remain open.”

Communities also need “adequate and timely” testing for the virus, with easy access, the AAP states. The association also advocates adequate funding — from federal, state and local sources — to cover the cost of mitigation, which the statement estimates could range from $55 to $442 per student.

Chapple says that any school or school district opening up for face-to-face instruction also needs a concrete plan for going back to virtual learning if the virus starts spreading more.

Without such a plan, she observes, school leaders may watch as community cases rise and wind up having to make a decision to close down on the fly. Instead, she says, schools need a clear set of public health metrics they can use to guide that decision.

“There needs to be a reopening plan, and there needs to be a plan to — when do we pull the switch and go back to remote,” says Chapple. “And those need to be set at the beginning.”

PHMDC is taking that position as well.

Accompanying the agency’s requirements for schools that are open for in-person classes is a list of six recommendations — items that are not part of the official health order, but that the department urges schools to follow voluntarily.

One of those recommendations states that schools teaching in-person need to “develop a plan to move to virtual instruction.”

That includes setting a threshold for shifting to all-virtual classrooms based on community trends in the number of positive cases of the virus, the extent of local exposure and the access to contact tracing locally to help limit the spread of an infection. The document includes a link to CDC guidelines on lower and higher risk factors for transmitting the virus in school.

In deciding not to open in-person teaching yet later this month, the Madison school district was essentially following the same principle.

“Throughout this pandemic, probably our number one lesson is — plan for all scenarios,” says Grande of PHMDC. “We still don’t know what the future brings. That element of the recommendations is really just to prepare for the unknown.”

Reprinted with permission of Wisconsin Examiner.

More about the Coronavirus Pandemic

- Governors Tony Evers, JB Pritzker, Tim Walz, and Gretchen Whitmer Issue a Joint Statement Concerning Reports that Donald Trump Gave Russian Dictator Putin American COVID-19 Supplies - Gov. Tony Evers - Oct 11th, 2024

- MHD Release: Milwaukee Health Department Launches COVID-19 Wastewater Testing Dashboard - City of Milwaukee Health Department - Jan 23rd, 2024

- Milwaukee County Announces New Policies Related to COVID-19 Pandemic - David Crowley - May 9th, 2023

- DHS Details End of Emergency COVID-19 Response - Wisconsin Department of Health Services - Apr 26th, 2023

- Milwaukee Health Department Announces Upcoming Changes to COVID-19 Services - City of Milwaukee Health Department - Mar 17th, 2023

- Fitzgerald Applauds Passage of COVID-19 Origin Act - U.S. Rep. Scott Fitzgerald - Mar 10th, 2023

- DHS Expands Free COVID-19 Testing Program - Wisconsin Department of Health Services - Feb 10th, 2023

- MKE County: COVID-19 Hospitalizations Rising - Graham Kilmer - Jan 16th, 2023

- Not Enough Getting Bivalent Booster Shots, State Health Officials Warn - Gaby Vinick - Dec 26th, 2022

- Nearly All Wisconsinites Age 6 Months and Older Now Eligible for Updated COVID-19 Vaccine - Wisconsin Department of Health Services - Dec 15th, 2022

Read more about Coronavirus Pandemic here

https://www.jsonline.com/story/communities/2020/11/05/wisconsin-schools-in-person-hybrid-virtual-coronavirus-pandemic/6165097002/

I’ll cut to the chase (do control F to confirm my results), in Wisconsin,

* 28 are open for in person learning

* 22 are hybrid

* 22 are closed (let’s round this to 1/3rd though less than 1/3rd)

So we have 2/3rds of schools in our area of schools open and hybrid and the results (I’m not seeing a 20/20 investigation).

MPS neighbors that are NOT 100% virtual: Elmbrook, Foxpoint-Bayside, Wauwatosa, Franklin, Germantown, Cudahy, Brown Deer, Cedarburg, etc.

Are we really unique? Are we the only school districts with poverty? with old bldgs?

What are the costs of being virtual?