Pandemic Still Hurting State Economy

Downturn far worse than during Great Recession. People’s fears, not shutdown orders, are driving downturn.

On March 19th, the downtown Milwaukee Punch Bowl Social laid off 91 employees. Photo by Jennifer Rick.

Five months into the COVID-19 pandemic, the economy — in Wisconsin and the nation — is limping under the weight of the virus.

Numbers released on Friday, Aug. 7, showed an increase of 1.8 million jobs in July nationally. “But, because so many jobs were lost in March and April, we are still 12.9 million jobs below where we were in February, before the pandemic spread,” wrote Elise Gould of the Economic Policy Institute in a blog post.

July’s gain in jobs was just a fraction of the 4.8 million jobs recovered in June and the 2.7 million in May.

“That is a little bit disconcerting,” says Dennis Winter, who heads the Office of Economic Advisors at the Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development. Wisconsin job numbers won’t be out for nearly two weeks, but generally they have followed national trends.

“Until infection rates are down to what seem to be acceptable levels, or there’s a vaccine or something to help people feel comfortable conducting their lives on a more normal basis,” Winter says, a robust recovery remains far off.

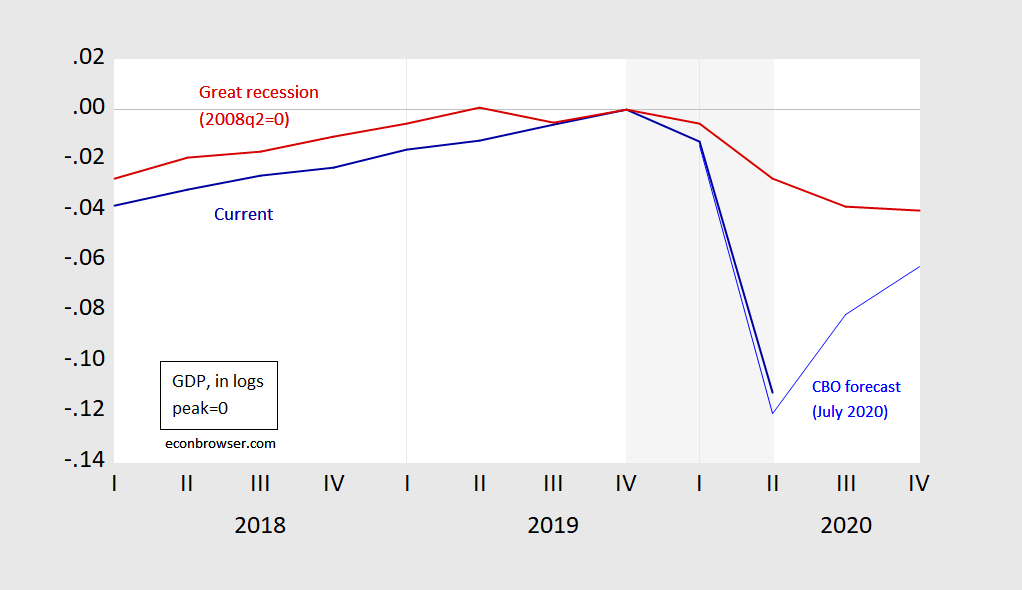

Deeper than 2008

The current recession is already much deeper than the Great Recession of 2008, says Menzie David Chinn, an economist at the UW’s Robert M. LaFollette School of Public Affairs, who produces a blog monitoring economic trends.

Comparison of the change in Gross Domestic Product for the 2008 recession (red line) and 2020 (blue line). (Graphic prepared by Menzie David Chinn, University of Wisconsin-Madison, for his blog Econbrowser; used by permission/Wisconsin Examiner.

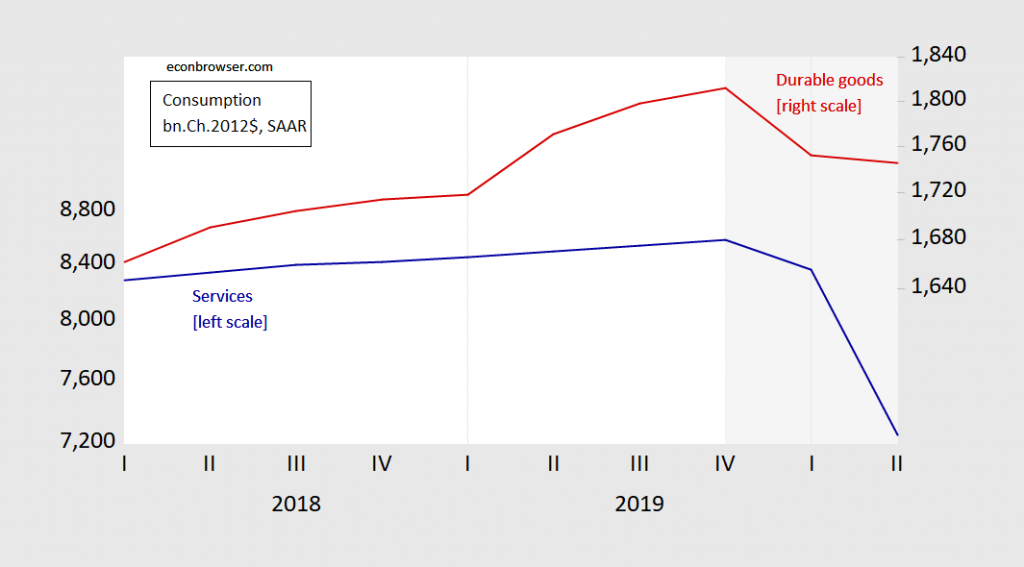

Unlike most recessions, it has been driven first by a decline in the service economy, exemplified by restaurants and the hospitality industry. Those businesses were immediately affected when both government orders and people’s fears of contracting the virus kept away customers.

Comparison of the changes in consumer purchases of services (blue line) and durable goods (red line) from 2018 through first two quarter of 2020 (gray shaded area at right). (Graphic prepared by Menzie David Chinn, University of Wisconsin-Madison, for his blog Econbrowser; used by permission/Wisconsin Examiner.

“If you were hoping for a recovery that brought us back to close to where we were at the end of last year — as long as we don’t tackle, in a serious way, the public health issue, then you’re going to be mistaken,” says Chinn.

“We tried to skip over the step of getting the infection rates to manageable levels,” he continues. “We are in what I feared, and many people feared, which was a sort of stop-and-go policy. We tried to get the economy going, but we don’t have the prerequisites in place.”

The virus, and people’s reaction to it, are at the root of the problem — not the Safer At Home order from Gov. Tony Evers that ran from March 25 until the state Supreme Court threw it out on May 13, says Steven Deller, an economist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s College of Agricultural and Life Sciences.

“The arguments that Gov Evers’ stay-at-home order lockdown caused the economic crisis in Wisconsin is overstating the case,” Deller says. “What caused the [economy’s] shutdown was — people were afraid that they could catch this thing and die. That’s what caused the collapse.”

In a recent analysis for the National Bureau of Economic Research, Austan Goolsbee and Chad Severson, both of the University of Chicago, used cell phone mobility data to measure people’s movements in metro areas with contrasting regulations. One example is the Quad Cities, which straddle the Mississippi River and the states of Illinois, which has had a strict shelter-in-place order, and Iowa, which has not.

“Legal shutdown orders account for only a modest share of the decline of economic activity,” Goolsbee and Severson write. Consumer traffic fell by 60 percentage points, but “legal restrictions explain only 7 [percentage points] of that.”

Where death rates from COVID-19 were higher, more people stopped going out, they found. And when shoppers did go out, they shifted away from larger, busier stores to smaller, less busy ones of the same kind.

One family’s experience

Kyra Swenson, a child care worker in Fitchburg, has been out of work since mid-March. The center that employed her closed when Evers ordered schools closed early in the pandemic. The center reopened in May, but with a smaller staff because many parents were home and chose to keep their children home, too. Swenson was called back to work in early July but turned down her position.

She did so for several reasons: because she had children at home herself, and because she was concerned that, while the center’s employees and children are in close quarters throughout the day, there was no requirement for people to wear masks to help limit the spread of germs.

“I’m an asthmatic,” Swenson says. “I have had pneumonia three times in the 12 years I’ve been working in child care. This is really scary for me.”

Her husband is a data analyst who was already working at home, and her low wages in child care made it affordable for her not to return to work, but in other ways the pandemic has changed how she and her family live their daily lives.

“We try to come into contact with people as little as possible,” Swenson says. “We don’t go into stores — I haven’t been in a grocery store since all this happened. We always do curbside pickup.”

“If we can get the number of deaths coming down, then people start to feel, ‘Well, maybe it’s not so risky — maybe I can go out and eat, may be I can go to the store and go get my hair cut,’ because the worst has been minimized,” Deller says.

But if people then get careless or complacent, he warns, there’s a risk of a resurgence that could send cases spiking again — as happened when after the court lifted the Safer At Home order people flocked to night spots and disregarded precautions.

And a new spike would be a greater blow to the economy. “If we go into this rollercoaster, consumer confidence is going to drop like a rock,” Deller says. “Then we’re in really serious trouble.”

What lies ahead

In the short term, Chinn sees the likelihood of “this really slow slog where we’re just kind of trending sideways” — as people take enough measures to slow the spread of the virus. But the state falls short of “the recovery we would have had” with a stronger, sustained and uniform public health response.

And without a new federal recovery package, “what we’ve seen so far is just a prelude and it will get a lot worse,” he warns. “You’ve got withdrawal of stimulus, and lots of uncertainty for lots of people, and that’s not conducive to people spending.”

The weekly federal $600 unemployment compensation supplement has expired, and Congress has yet to reach a deal that would include that measure or several others, such as suspending evictions. And there isn’t yet any aid to make up for lost tax revenue to state and local governments. “So they’re going to retrench,” says Chinn — cutting essential services, many of which go to low-income people.

Although a series of executive orders and memos that President Donald Trump signed on Saturday purported to address the unemployment extension and evictions, outside analysts asserted they amounted to little.

The order replaces the $600 supplement with $300, but also requires states to add $100 of their own funds. Another memo directs federal agencies to “consider” suspending evictions but has no other force.

“It’s not clear how much incomes will be sustained,” says Chinn of the unemployment compensation order, “especially as the levels are lower and even that is contingent on states topping off 25% of the addition.”

Another order defers collection of the payroll tax — but “payroll tax reductions don’t help those who are unemployed,” he adds — and people who are working will still owe the money at tax time. Nor would it boost hiring, because labor costs aren’t holding down employment.

“Even if all these were to go into effect, they’d be far short of what is needed,” Chinn concludes. “And if this is all we get, it’ll be a disaster going forward.”

Reprinted with permission of Wisconsin Examiner.

More about the Coronavirus Pandemic

- Governors Tony Evers, JB Pritzker, Tim Walz, and Gretchen Whitmer Issue a Joint Statement Concerning Reports that Donald Trump Gave Russian Dictator Putin American COVID-19 Supplies - Gov. Tony Evers - Oct 11th, 2024

- MHD Release: Milwaukee Health Department Launches COVID-19 Wastewater Testing Dashboard - City of Milwaukee Health Department - Jan 23rd, 2024

- Milwaukee County Announces New Policies Related to COVID-19 Pandemic - County Executive David Crowley - May 9th, 2023

- DHS Details End of Emergency COVID-19 Response - Wisconsin Department of Health Services - Apr 26th, 2023

- Milwaukee Health Department Announces Upcoming Changes to COVID-19 Services - City of Milwaukee Health Department - Mar 17th, 2023

- Fitzgerald Applauds Passage of COVID-19 Origin Act - U.S. Rep. Scott Fitzgerald - Mar 10th, 2023

- DHS Expands Free COVID-19 Testing Program - Wisconsin Department of Health Services - Feb 10th, 2023

- MKE County: COVID-19 Hospitalizations Rising - Graham Kilmer - Jan 16th, 2023

- Not Enough Getting Bivalent Booster Shots, State Health Officials Warn - Gaby Vinick - Dec 26th, 2022

- Nearly All Wisconsinites Age 6 Months and Older Now Eligible for Updated COVID-19 Vaccine - Wisconsin Department of Health Services - Dec 15th, 2022

Read more about Coronavirus Pandemic here