The Idea Activists and Police Agree On

Why are cops still being sent to respond to mental health crises?

More than two months since the beginning of a national reckoning over criminal justice and policing, it sometimes seems as though advocates from every side of the debate have settled into their respective corners.

After some initial progress on policies such as removing cops from schools and shifting municipal budget priorities — the debate in Wisconsin has slowed as activists continue to march in the streets and legislative leaders continue to say action won’t come until at least the fall.

But there is a policy idea that has the potential to gain traction among cops and Black Lives Matter activists alike — getting the police out of the business of responding to mental health crises.

For activists, armed officers responding to people experiencing a mental health crisis is a recipe for disaster. Since 2015, 5,480 people have been shot and killed by police and 22% of them — 1,226 — were in a mental health crisis, according to a Washington Post database of fatal police shootings.

The police come at this issue from a different angle, but by no means do they completely disagree.

For the cops, responding to mental health calls is stressful, time consuming and expensive. These mental health calls have become increasingly common as treatment resources have dwindled. Officers regularly escort people in the throws of a crisis to a single in-patient mental hospital near Oshkosh — regardless of where they’re coming from. This can take an officer off patrol for up to 12 hours, longer than a typical shift, which means the municipality needs to pay for overtime and another patrol officer to cover the shift.

“The vast majority of officers, they’re largely limited to the Winnebago Mental Health Institute near Oshkosh,” Jim Palmer, director of the Wisconsin Professional Police Association, says. “[It’s an] enormous drain on resources, diminishes an agency’s staffing.”

“A totally inadequate response to individuals suffering from a mental health crisis,” he continues. “There’s been some legislative interest in this. I also think this would be a perfect area for a committee to explore and develop models for alternatives to crisis intervention police — social workers, mental health professionals.”

If Adams and Palmer sat down in a room they would disagree over specifics, but the fundamental structure of the policy is there. Instead of having the police respond to these calls, send an entirely different team of first responders who are trained and equipped to de-escalate the situation and help the person.

If a building is on fire and someone calls 9-1-1, the fire department arrives. If someone has a heart attack and 9-1-1 is called, paramedics will arrive. So, if someone is having a mental health crisis, why not have — as Palmer put it — social workers and mental health professionals arrive?

Adams put it more plainly. A mental health crisis is a health problem that requires a health-based solution.

“Would we be sending in police to cure cancer?” Adams says. “Why would we have a cancer department of the police?”

This also isn’t a new idea. Since 1989, an initiative run by the White Bird Clinic in Eugene, Ore. called Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets (CAHOOTS) has been filling this role. The program is dispatched through the 9-1-1 and police non-emergency line.

When a call comes in, an unarmed team of two with a medic and a crisis worker arrive on the scene. In 2019, CAHOOTS was sent to 20% of the calls for service. In only 250 of those 24,000 calls were police officers called for backup, according to a CAHOOTS media guide.

“I think policing may have a place within this system, but I also think that it’s over-utilized as an immediate response because it just comes with a risk,” CAHOOTS Crisis Worker Ebony Morgan said on NPR’s All Things Considered. “And it’s a risk that crisis response teams that are unarmed don’t come with. You know, in 30 years, we’ve never had a serious injury or a death that our team was responsible for.”

Policymakers in Wisconsin have been thinking about this issue as well — with bipartisan cooperation.

In October 2019, Wisconsin Attorney General Josh Kaul held a summit on “Emergency Detention and Mental Health.” Law enforcement, healthcare professionals and mental health advocates came together to discuss the trauma caused, as well as the time and money spent, when the cops need to drive someone to Winnebago.

In February, Gov. Tony Evers signed into law Act 105. The bill, authored by Rep. Mark Born (R-Beaver Dam), allows municipalities to contract with third-party vendors when a person needs to be transported to a mental health facility. While it doesn’t take the cops out of the response to the crisis, it was a small step closer.

“Putting someone in a mental health crisis in the back of a sheriff’s car isn’t the best idea to start,” Rep. Dave Considine (D-Baraboo) said at the time.

Since Evers signed the bill, obviously a lot has changed and issues surrounding Wisconsin’s systems for health and policing have been unmasked — the scope of necessary and possible policy solutions have broadened.

Palmer says he wants the WPPA to be a driver of the discourse over the role of policing in Wisconsin and that he believes changes are necessary. He said opening regional mental health centers and creating a CAHOOTS-like pilot program are possible solutions.

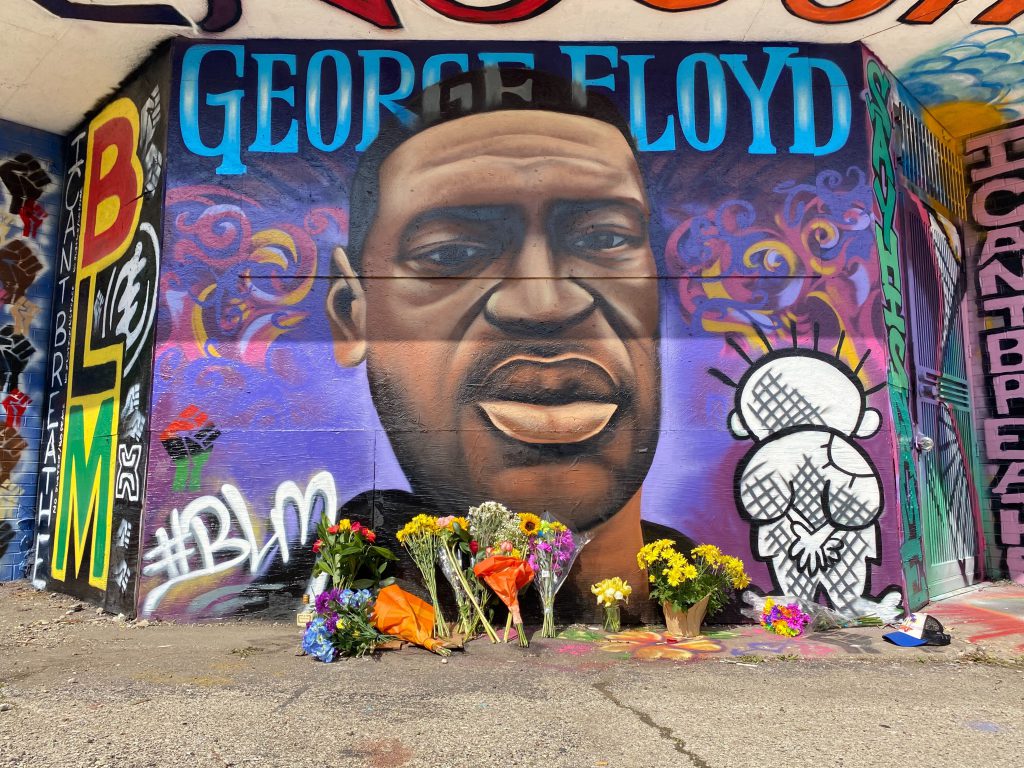

The WPPA has also had conversations with members of the Wisconsin Legislative Black Caucus and plans to release a list of policy proposals soon, according to Palmer. But, with two months already gone since the killing of George Floyd, he doesn’t think major action will be taken this year.

Adams, who sees something like taking the police out of mental health response in the scope of a much larger goal to defund the police, says it’s not unreasonable anymore to think that the cops shouldn’t be responsible for certain types of problems.

“Here’s the thing, I’m an abolitionist, but I think reasonable people can conclude policing shouldn’t be used for a set of functions,” Adams says. “I think CAHOOTS is an example of what could be. That is a model we should look to.”

“We’re here with policing because [the police have] been heavily invested in,” Adams continues. “We could better fund preventative healthcare, these issues could be caught at the ages of onset. People have comprehensive care. Instead of hiring people to kill people, they could create a different jobs program of city workers, cultural workers, health workers, therapists that people could be inside of and have a different role and relationship in society.”

Born and members of the Black Caucus did not return requests for interviews.

Reprinted with permission of Wisconsin Examiner.

More about the 2020 Racial Justice Protests

- Plea Agreement Reached On Long-Pending Sherman Park Unrest Charges Involving Vaun Mayes - Jeramey Jannene - Oct 17th, 2024

- Rep. Ryan Clancy Settles With City Following 2020 Curfew Arrest - Jeramey Jannene - Dec 12th, 2023

- Supervisor Clancy Applauds Settlement in Clancy vs. City of Milwaukee - State Rep. Ryan Clancy - Dec 12th, 2023

- Tosa Protest Assails Federal Court Decision Exonerating Police - Isiah Holmes - May 9th, 2023

- Wauwatosa ‘Target List’ Trial Begins - Isiah Holmes - May 3rd, 2023

- Shorewood Spitter Found Guilty For 2020 Protest Confrontation - Jeramey Jannene - Apr 20th, 2023

- City Hall: City Will Pay 2020 George Floyd Protester $270,000 - Jeramey Jannene - Feb 14th, 2023

- Tosa Protest Tickets Dismissed - Isiah Holmes - Jul 21st, 2022

- Op Ed: ‘We Need More’ - Charles Q. Sullivan - Mar 4th, 2022

- Milwaukee Officers Circulate “2020 Riot” Coins? - Isiah Holmes - Nov 14th, 2021

Read more about 2020 Racial Justice Protests here

The critical change has to be made to the chapter 51 involuntary commitment process. Need to remove police from this process altogether.