Do ‘Checkoff Groups’ Help or Hurt Family Dairy Farms?

Federally-required agricultural promotion organizations may not benefit small dairy farms

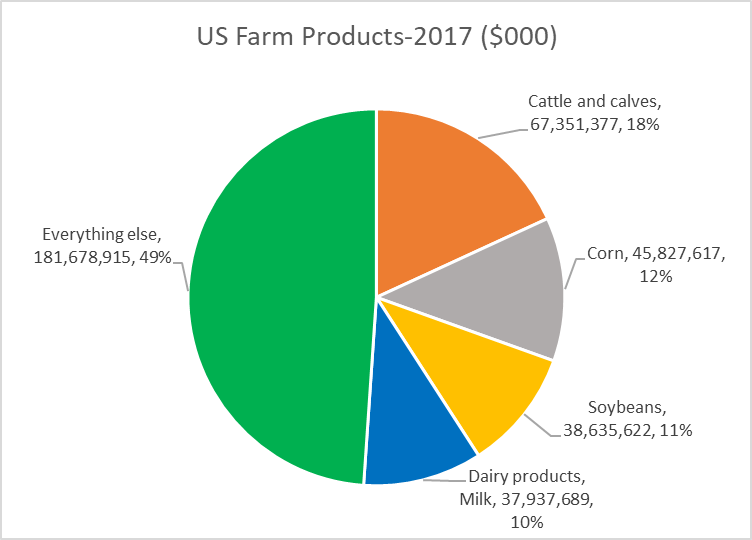

The association of Wisconsin with family dairy farms is far more than a slogan on a license plate. Wisconsin means dairy. As the next graph shows, dairy products account for 10% of the value of all agricultural products nationally (shown in blue).

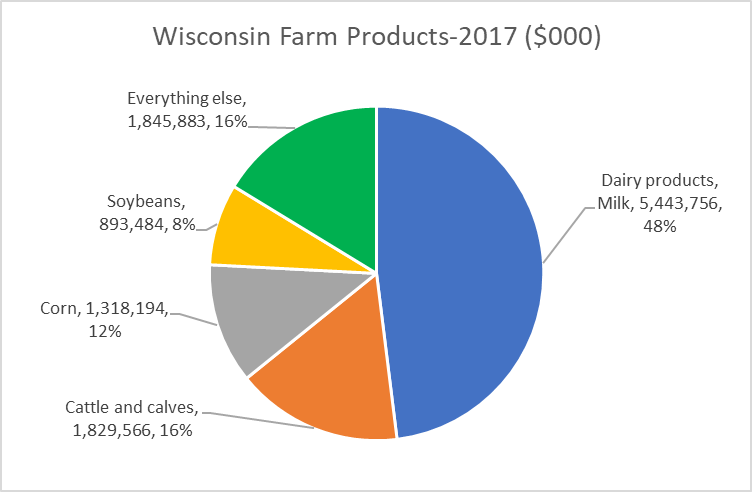

Compare that to the mix of farm products in Wisconsin. As shown in the next graph, dairy products are close to half of agricultural product—at least in 2017.

The view that Wisconsin equates to family dairy farming closely comports with reality. My grandfather, a New Jersey dairy farmer, almost never took a vacation. After all, someone had to milk the cows morning and evening. The only exception came when he and my grandmother took a weeklong trip to buy cows in Wisconsin.

Donald Trump was elected in large part because Wisconsin’s rural counties–presumably including many dairy farmers–switched their vote. This support was not reciprocated by the new administration. Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue’s joke as reported by Newsweek:

What do you call two farmers in a basement?

A whine cellar.

At the World Dairy Expo in Madison, Perdue opined that small family dairy farms have little future:

Now what we see, obviously, is economies of scale having happened in America — big get bigger and small go out. … It’s very difficult on economies of scale with the capital needs and all the environmental regulations and everything else today to survive milking 40, 50, 60 or even 100 cows, and that’s what we’ve seen.

Although Perdue points to the market as the cause of the dairy family farm crisis, government policy also played a role. Examples are Trump’s tariff war against America’s trading partners and Scott Walker’s willingness to overlook the environmental effects of huge dairy operations.

Recently critics have targeted the so-called “checkoff” organizations established by federal law. Under these laws, farmers and ranchers are required to pay fees to these organizations to fund marketing efforts aimed at increasing demand for their products. The long-running “Got milk” campaign, which showed pictures of celebrities with white milk mustaches, is perhaps the best-known example.

According to an article in the Journal Sentinel, dairy producers are, by far, the biggest contributors to the checkoff programs, last year paying about $420 million, or 47%, of all checkoff money. According to the article, about $155 million of that went to Dairy Management Inc.

When family dairy farms are going out of business at a rate of almost two a day in Wisconsin, lavish executive compensation also leads to criticism. According to the Journal Sentinel, 10 executives at Dairy Management were paid an average of more than $800,000 each.

In addition, critics argue that checkoff organization activities favor larger farms to the detriment of family farms. For example, they argue that the Dairy Management’s partnerships with fast food and other large companies are more beneficial to large producers than smaller family farms.

The Journal Sentinel article points out that critics of the checkoff programs represent an unusual coalition:

It isn’t often the Humane Society of the United States aligns itself with dairy farmers, ranchers, environmental groups and the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank.

Taking the lead in challenging the checkoffs is the Organization for Competitive Markets. Surprisingly, given the magnitude of the dairy checkoff, this group’s website shows little dairy participation.

Defenders of checkoff organizations include much of the agricultural establishment including major food processors, the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, the National Pork Producers Council and the American Farm Bureau.

Responding to these criticisms, two bills have been introduced in the US Senate. The first is the Opportunities for Fairness in Farming Act of 2019, sponsored by Utah’s Mike Lee. Co-sponsors are Rand Paul of Kentucky, Cory Booker of New Jersey and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts. The sponsorship is strikingly bi-partisan. Lee and Paul are generally considered among the most conservative Republicans with a strong libertarian streak. Booker and Warren are running for the Democratic presidential nomination.

This bill prohibits lobbying, conflicts of interest, “any anticompetitive activity”, “any unfair or deceptive act or practice”, and “any act that may be disparaging to, or in any way negatively portray, another agricultural commodity or product.”

A second bill, also sponsored by Lee and called the Voluntary Checkoff Program Participation Act, would make the checkoff programs voluntary. It is also cosponsored by Senators Paul and Booker. Although Warren is not listed as a co-sponsor, a statement from her campaign posted on Medium makes it clear she is a supporter:

We need to reform the checkoff programs to root out corruption. I support legislation that will make the checkoff program voluntary and ensure that Boards cannot engage in anti-competitive practices or lobby the government.

Will these bills, if enacted, help counter the present disappearance of small farms, particularly of dairy farms in Wisconsin? Several provisions–such as the requirement for transparency–are clearly beneficial. Others may work against the interest of family farms.

Making the checkoff voluntary may harm the interest of family farmers. To understand why, it is useful to start with economists’ concept of public goods. A public good has two characteristics:

- It is “non-rivalrous.” Consumption it doesn’t reduce the amount available for others. Benefiting from a streetlight doesn’t reduce the light available for others but eating an apple does.

- It is “non-excludable.” It is hard to provide the good without providing it to those who don’t pay. Anyone travelling on the street benefits from the light, whether or not they pay.

Assume that a program funded by a checkoff is effective in increasing demand for an agricultural product. From a farmer’s viewpoint, it acts very much like a public good. Making the checkoff voluntary means that the benefits are not excludable. Free loaders get the benefit at no cost.

Knowing they will benefit whether or not they pay, hard-pressed family farmers are likely to avoid paying. As a group, however, these farmers are likely to see their influence further diminished as a result.

Opponents of labor organizations are well aware of this principal. By making union dues voluntary through so-called “right-to-work” legislation they succeed in weakening or destroying unions, shifting the power balance to favor capital over labor. Similarly, while the intentions of the sponsors of these two bills are good, they may end up shifting influence further in the direction of large organizations.

To reverse the decline of family dairy and other farms, a useful start is acknowledging the divergence of interests among agricultural producers. Given this divergence, it is hard for any checkoff organization, no matter how well intentioned, to represent the interest of both a large feeding operation and a family organic farmer. Rather than making the checkoff voluntary, one answer is to offer the farmer a choice of checkoff organizations. Thus, an organic farmer could choose to support an organization that promoted milk coming from organic farms.

Instead, the bills attempt to paper over the deep fissures in the agricultural community by banning lobbying or “disparaging … another agricultural commodity.” A better approach might allow farmers to choose an organization that best represents their interests and lobby and market accordingly.

Data Wonk

-

The Myth of Immigrant Violence

Feb 5th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Feb 5th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Much Did New State Legislative Districts Change?

Jan 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Jan 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

Crime, Trump’s Claims and The Facts

Jan 8th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Jan 8th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson