Posters of Gay Paree

Milwaukee Art Museum’s show of 19th century posters by illustrator Jules Cheret is pure fun.

![Jules Chéret (French, 1836-1932) Le Courrier Français: Exhibition of 1,200 Original Drawings [Le Courrier français: Exposition de douze cents dessins originaux], 1891. Color lithograph. Promised gift of James and Susee Wiechmann. TR2016.5.351. Photo by John R. Glembin.](https://urbanmilwaukee.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/19_header-petite_posters-01-403x590.jpg)

Jules Chéret (French, 1836-1932) Le Courrier Français: Exhibition of 1,200 Original Drawings [Le Courrier français: Exposition de douze cents dessins originaux], 1891. Color lithograph. Promised gift of James and Susee Wiechmann. TR2016.5.351. Photo by John R. Glembin.

The Milwaukee Art Museum’s current exhibit, Petite Posters: Jules Cheret and Le Courrier francais, on display through November 17 in Level 2 of the museum in Gallery 202 of the European Art Galleries, showcases about a dozen of Cheret’s colorful lithographs and an edition of the weekly publication Le Courrier francais. These posters are a small part of a 600-piece collection of Cheret’s works, a promised gift to the MAM by Susee and James Wiechmann.

Beginning in 1884, Cheret’s advertisements, financed by the pharmacist Auguste Geraudel, were printed in Le Courrier francais. Founded in 1884 by Jules Roques, a publicity broker, Le Courrier celebrated the art of advertising, which was a new industry at the time, but one that would experience staggering growth in decades to come and have an indelible impact on sales and marketing.

Cheret’s work became very popular, and many Le Courrier subscribers purchased his posters to hang in their homes. In turn, the journal published a number of Cheret’s illustrations (in addition to his advertising lithographs) and ran an edition dedicated to his works, in conjunction with the artist’s Parisian solo exhibition in 1890. Le Courrier help propel Cheret to great success, and he soon gained large manufacturing and railroad companies as advertising clients.

Nikki Otten, the museum’s Associate Curator of Prints and Drawing, said curating Petite Posters “allowed me to examine a lesser-known aspect of Cheret’s career and illuminate the role the magazine played in elevating the status of his art.”

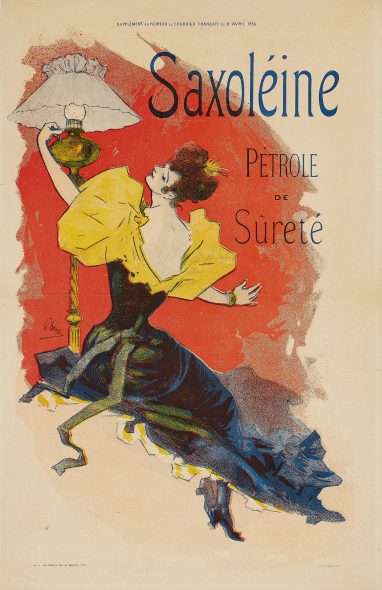

Jules Chéret, Supplément au numéro du Courrier français: Saxoléine, 1894. Color lithograph. Promised gift of James and Susee Wiechmann, TR2016.5.149. Photo by John R. Glembin.

Cheret’s posters feel light and airy. His carefree subjects, mainly women, enjoy the finer things in life—a delicious meal in an upscale café, a glass of top-shelf liquor; stunning clothes in the latest fashions, made of sumptuous fabrics. Fur wraps and tall hats with feather plumes were considered haute couture at the time, and Cheret’s illustrated women carry them off with aplomb. Some of the women are pictured holding regal white cats—Persians, perhaps.

Several posters, including one advertising a masquerade ball, tend towards the fanciful. Cheerful clowns are linked arm-and-arm with laughing women; theatrical performers dressed in outlandish costumes pose for a picture. The French “joie de vivre” was exalted through Cheret’s ads; it’s apparent he was intrigued by the vibrant nightlife in Paris, particularly the Montmarte district, a haven for artists and theater actors at the time.

To many, Cheret’s posters appear progressive. Women casually imbibing alcohol and smoking cigarettes, for example, is a stark contrast to the prim and proper societies of Europe and America during the late 1800s, in which such behavior among women was considered scandalous (and dangerous, according to the Temperance Movement of the time). The women portrayed in Cheret’s posters became known as “Cherettes,” and their uninhibited, fun-loving attitudes and appearances had a positive impact on French women, who followed suit.

Petite Posters reveals the amount of artistry and creativity behind these early advertisements, and the impact of advertising, which then and now has a remarkable ability to shape fashion, art, culture and societal norms.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits, all detailed here.

Art

-

Winning Artists Works on Display

May 30th, 2024 by Annie Raab

May 30th, 2024 by Annie Raab

-

5 Huge Rainbow Arcs Coming To Downtown

Apr 29th, 2024 by Jeramey Jannene

Apr 29th, 2024 by Jeramey Jannene

-

Exhibit Tells Story of Vietnam War Resistors in the Military

Mar 29th, 2024 by Bill Christofferson

Mar 29th, 2024 by Bill Christofferson

Review

-

Ouzo Café Is Classic Greek Fare

May 23rd, 2024 by Cari Taylor-Carlson

May 23rd, 2024 by Cari Taylor-Carlson

-

‘The Treasurer’ a Darkly Funny Family Play

Apr 29th, 2024 by Dominique Paul Noth

Apr 29th, 2024 by Dominique Paul Noth

-

Anmol Is All About the Spices

Apr 28th, 2024 by Cari Taylor-Carlson

Apr 28th, 2024 by Cari Taylor-Carlson