The Lost Legacy of Harry Weese

Why the Marcus Center and Kiley grove are not historic.

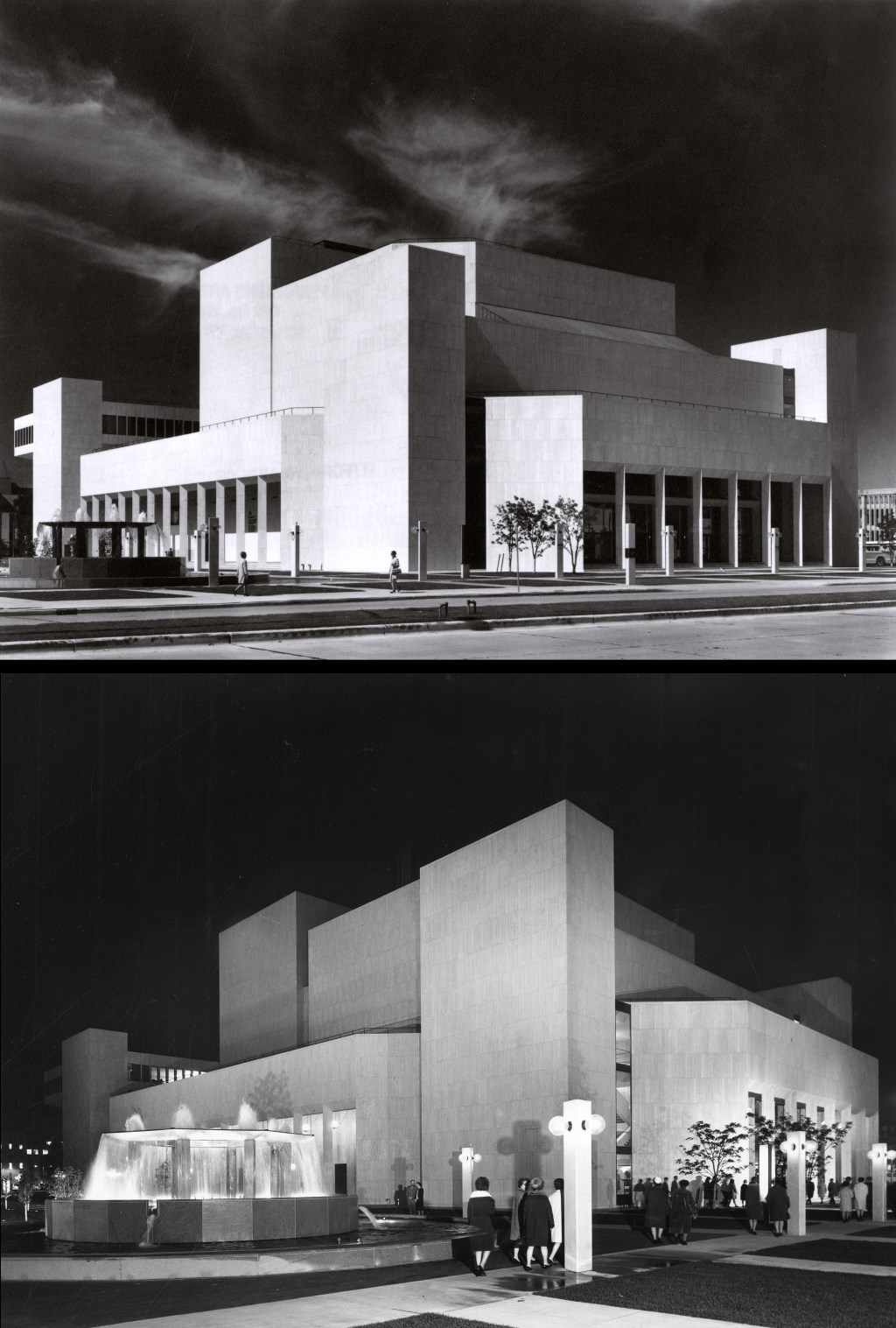

“City Has a Night to Remember,” was the headline of the Milwaukee Journal on September 17, 1969. The balcony seats cost $100, nearly $700 in today’s dollars. The Performing Arts Center by Harry Weese was really something.

Weese was at the peak of his powers working in Wisconsin during the late 1960’s. He finished the IBM building at 611 East Wisconsin Avenue in 1965, the Mosse Humanities building in 1969 in Madison, and The Elvehjem/Chazen Art Museum in Madison in 1970. In 1976 the first leg of Weese’s Washington Metro System opened. “Mr. Weese designed a systemwide network of stations that rank among the greatest public works of this century,” wrote Herbert Muschamp, the New York Times architecture critic.

Weese lived in a time when architects tried to make elemental buildings. That is, finally get rid of all the Victorian bric-a-brac, the frosting that has been attached to buildings throughout the ages. Weese never fussed nor deviated from using muscular forms and unadorned materials. He followed the rules, his rules. It was more than a style. Modernist architects thought they found the truth of architecture.

Top photo by Andrea Izzotti / Shutterstock.com. Bottom photo by Ben Schumin [CC BY-SA 3.0]

His favorite material was precast concrete. Hence the name Brutalist Architecture, which comes from the French béton brut (raw concrete). The movement peaked in the 1970s after which the name took on the common sense meaning of the word brutal.

“The severe cement facade strikes many as overly imposing,” according to the Badger Herald, “looking less like a hub of arts and history and more like a munitions plant from some bleak dystopian fiction.” It was slated for demolition in 2011. The Mosse building may be a bit overbearing. But today it’s a relief from the real estate boom in Madison that has produced many buildings with no bearing whatsoever.

Weese’s honest simplicity holds up because his buildings stood for something. The 1970’s was a culmination of a distillation process. Buildings should be fundamental. Weese wanted a building to be the thing itself.

Weese elevated his game for The Performing Arts Center. For starters it was clad with white Italian travertine marble. Nothing brutal about this sumptuous material that infused the building with light. The PAC glowed in the light and dark.

The PAC is part illusion. The building was white before it was anything else. The luminescence of the marble abstracted forms, lifted and softened the building.

The PAC was an advance for Weese. He substituted lucidity for rawness and refined so-called brutalism without sacrificing its forthrightness. The building had the clarity of a mathematical equation. The result was ethereal.

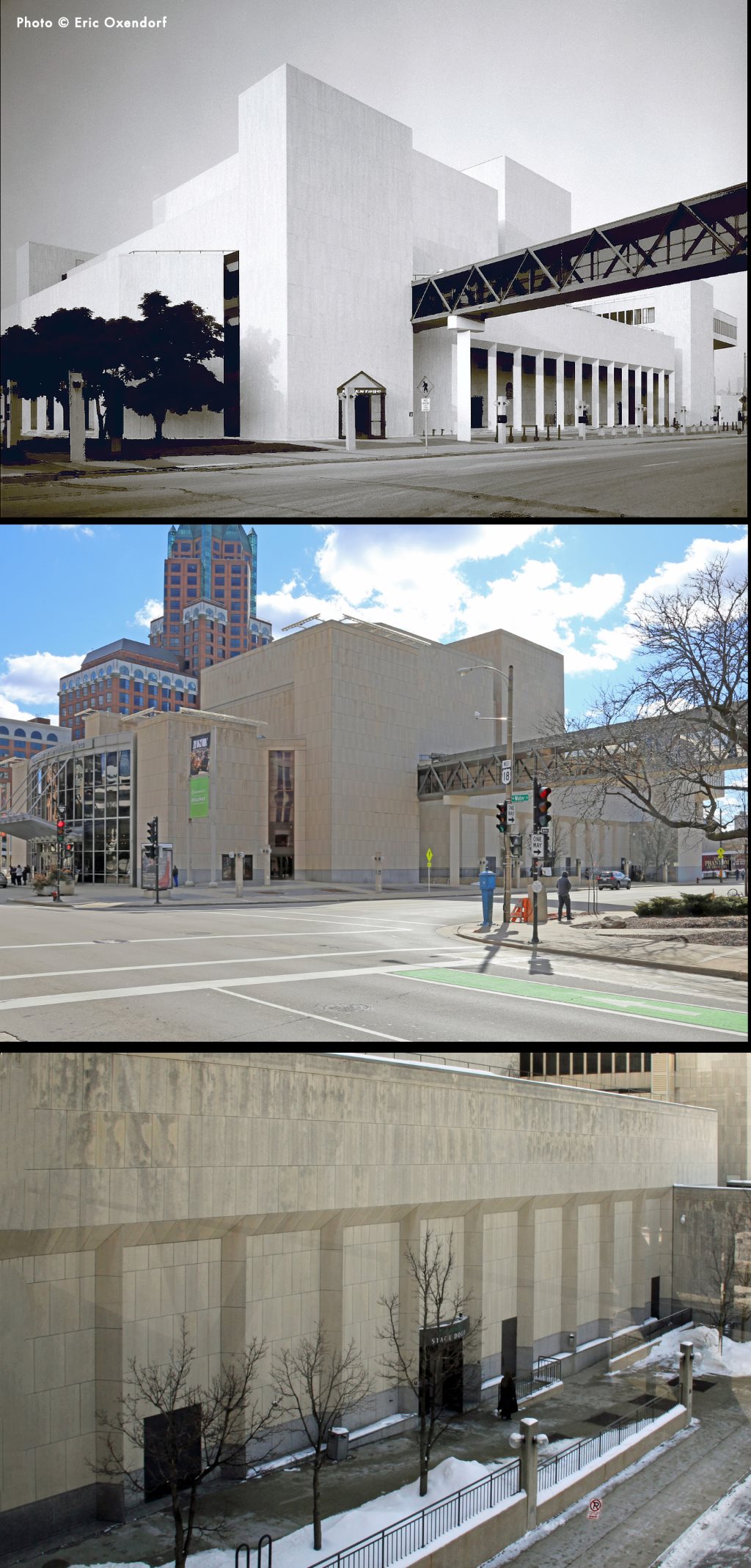

It didn’t take much to bring this building down to earth. In 1994 the marble was replaced by a mixture of limestone and granite that took the gleam off the building. It’s taupe, the color of kitchen appliances in the 1970’s. The thrill was gone. The PAC lost its iridescence.

Think of a sugar cube in the morning light. Then add coffee. The new cladding muddied the composition, took the lilt and light out of the PAC, deflated the building into a sunken incoherent mass. White was innate to the structure of building. They turned a fresh mint into a milk dud.

Two years later a 40 foot addition to the lobby along North Water Street was tacked on and two of the three colonnades that ran along the sides of building were filled in, turning the building into a brick with a new name — the Marcus Center for the Performing Arts.

The new entrance/lobby replaced the angles, that are reiterated throughout, with blocks that hold up a curved black glass entrance. It looks like an attachment you could pick up at Home Depot. Today black glass is architectural heresy. Adding insult to injury, new LED lights were recently cantilevered over the top edges of the building.

None of this would have devastated Weese’s Mosse Humanities building in Madison. But the PAC was a delicate piece of work.

The PAC lost the idea of itself, the grammar that held the building together. I am talking about the clarity of the lines and forms, the positive and negative spaces that projected the building upward.

The LED light arrays would have stood out like a vulgar piece of costume jewelry on Weese’s PAC. You hardly notice them on the Marcus Performing Arts Center.

The lights are being used to cover up a crime. Here’s the way the building is portrayed today on the Marcus Center’s website.

So how could the Historic Preservation Commission designate this building a historic structure? Because it can. Why did it do it? It had an ulterior motive — stop the Marcus Center from replacing Dan Kiley’s distressed grove of trees with a new more open design.

Mary Louise Schumacher and Whitney Gould, two former architectural critics of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, wrote to the Common Council urging them to affirm HPC’s designation at an upcoming meeting. Buildings like Weese’s Marcus Center are “important exemplars of their time and place,” the critics wrote, “allowing us to ‘read’ the passage of time in the built environment.”

But it’s not Weese’s Marcus Center. The demise of his PAC is a cruel lesson that should be remembered instead of preserved. The building no longer makes sense, which was of paramount importance to Weese. HPC’s designation makes no sense either. Weese’s design lost its integrity and the HPC its credibility.

So what about the grove? I have written about Kiley here and photographed his work in front of the Milwaukee Art Museum for a recent exhibition put together by the Cultural Landscape Foundation. Every summer I sit in Kiley’s grove and am struck by the tranquility of the place, an oasis apart from the rest of the city. I love his work.

That said, the obliteration of the Weese building has changed the impact of the grove. Kiley’s austere modernist conception went with Weese’s interpretation of the building, which is now gone. And now that the Marcus Center is renovating its campus, it will be mandated to provide handicapped access, requiring it to make the grove less sunken and/or replace the gravel floor under the trees.

But those are smaller (if important) points compared to the fact that four trees in the grove are dying and must be cut down. The HPC’s solution to this literally misses the forest for the trees. They’ve mandated the four trees that were cut down before they fell have to be replaced within a year. Thirty-two big trees and four little ones is a nullification of Kiley’s “sacred geometry” as he called it. His work is not about this tree or that. It’s all about how trees are organized. It’s a grove of trees, all the same age and type. The uniformity and symmetry of the grid is what matters.

The HPC doesn’t understand that Weese’s building and Kiley’s grove are ideas. To truly preserve the Kiley grove you would have to start from scratch, as they’ve done in the Tuileries Garden in Paris, cutting down the trees when they get old enough and replacing them with a new group of uniform age and appearance.

But under the law the HPC cannot require a historic building be rebuilt from scratch, or that the Marcus Center replace the entire grove. It can only require restoration — the replacement of the failing trees — which will inevitably be asymmetrical and contrary to Kiley’s vision. In doing so the HPC won’t be restoring but changing history, an odd thing for a historic commission to do.

In Public

-

The Good Mural

Apr 19th, 2020 by Tom Bamberger

Apr 19th, 2020 by Tom Bamberger

-

Scooters Are the Future

Dec 19th, 2019 by Tom Bamberger

Dec 19th, 2019 by Tom Bamberger

-

Homeless Tent City Is a Democracy

Aug 2nd, 2019 by Tom Bamberger

Aug 2nd, 2019 by Tom Bamberger

Brilliant! Thanks for your clarity and artistic intelligence in detailing the protracted demise of the once-beloved Performing Arts Center as an icon of historic architectural value.

Here’s an interview with someone who was on the design team about the thinking behind the horse chestnut grove.

https://www.milwaukeemag.com/thinking-behind-marcus-centers-famous-chestnut-grove/