Kiley’s Chestnut Grove Provokes Hot Debate

Should it be saved? Or past its prime? At stake is the past and future of a changing city.

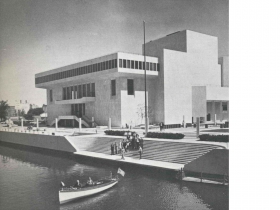

Updated rendering of the Marcus Center for the Performing Arts’ redevelopment plans. Rendering by HGA.

Jim Shields is passionate about great architecture, and that includes the work of landscape architect Dan Kiley. “I probably have seen six or seven of his projects,” he says. “I’ve even seen his work in Paris. I have a lot of respect for his work.”

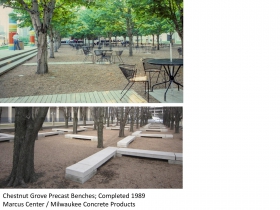

But Shields is now in the strange position of overseeing the elimination of the 50-year-old chestnut grove created by Kiley for Milwaukee’s Performing Arts Center in 1969. The grove would go as part of a major renovation of the facility, now known as the Marcus Center for the Performing Arts.

“We will definitely take the blame for destroying” the Kiley grove, Shields told Journal Sentinel critic Mary Louise Schumacher, in a quote he surely regrets. This was in a story for the JS just before Schumacher departed after taking a buyout.

Shields feels the story was misleading because Schumacher wrote that “they will rip out the sunken garden and trees and replace it with a rectangle of grass.” In fact, Shields has a pretty major plan to replace two of Kiley’s four rows of trees in a kind of homage to Kiley. But that barely came through in the story, in particular because the Marcus Center’s first architectural rendering, which illustrated the story, showed just a bare-looking lawn.

“I’ve had people come up to me and ask ‘why are you replacing the Kiley grove with a lawn?’,” Shields complains.

I’ve talked with Shields and longtime architecture critics Whitney Gould and Tom Bamberger, and with Jennifer Current, a local landscape architect who has taught at several universities, and is leading the charge to save the Kiley. All make powerful arguments on each side of the debate.

There is no debate over the quality of what Kiley created on Water and Kilbourn streets. “The Dan Kiley chestnut grove is quite simply a modernist masterwork, a little island of Parisian civility on a busy urban site,” Gould says. “Kiley was a visionary who knew how to turn nature into living, breathing architecture, with its own formalist design language rooted in classical principles.”

Bamberger wrote a story for Urban Milwaukee championing the “sacred geometry” of Kiley, and pointed to works like the chestnut grove as examples of Kiley’s “uncanny ability to wrap a mystery around straight lines.”

For Current, the grove is unique in that it is so exposed, with its location on a busy street, and yet so enclosed. “There are no walls, but it feels like a closed space. I can’t think of any works of his that offer the same sense of immersion on such a busy corner. It is so rare. And by such a master.”

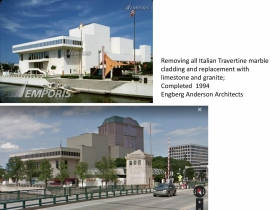

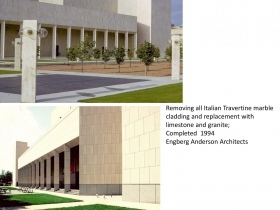

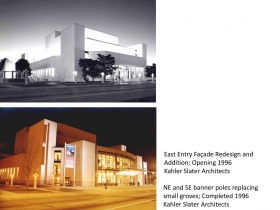

But the work was built to complement a particular building, the Harry Weese-designed PAC, which has gone through several major renovations, including a complete re-cladding, replacing the Italian marble (“I consider this a fatal blow,” Shields has said), and replacing a colonnade entrance with an expanded lobby and large glass facade.

Gould contends the changes haven’t been fatal. “The building retains the monumentality of its Brutalist style” and now has “a warmer more refined kind of Brutalism,” she believes. Current argues that whatever the changes the building was “part of an arts revival in the city” and is a civic landmark “that is still important today.’

Bamberger, however, says that “none of the changes to the building were done with any respect for the original design.” It’s “lost the original vigor and joy of the building,” he believes.

Like Shields, he feels the re-cladding was the fatal blow: “The original white marble softened all the forms of the building. It kind of floated. You make it that light brown and the whole thing falls flat.”

Would Kiley have built the same kind of grove for the radically altered version of Weese’s building? Bamberger isn’t sure: “His austere modernist groves went with Weese’s interpretation of the building.” Kiley’s landscapes, he notes, were often paired with buildings by Weese or Eero Saarinen.

But Gould and Current don’t see that as an issue, and interestingly, neither does Shields.

But Shields contends that 50 years after it was created, “the grove is probably at the end of its usable service life.”

As Jannene reported, an arborist hired by the Marcus Center found four trees that were in “very poor” condition and could fall over. Shields says the arborist found five additional trees that are in “poor” condition which could be in very poor condition in just the next few years. “That’s one quarter of the grove. How many trees can you lose till you lose the integrity of the thing?”

The city’s arborist found only two trees were past salvaging, and suggested two others could be braced with metal rods, Jannene reported. But “it will still create a dissymmetry from the grove. You will have trees that will be different,” the arborist noted.

Kiley’s creation was four rows of nine trees, each the same type and height and age. “If one of those trees is lost, it’s all over,” Bamberger argues. “It’s all about rationality and symmetry, that’s his vision. It’s the perfect grid, that’s the joy of it.”

Gould concedes there might be a loss, but contends “it would be better to restore the site more or less as Kiley envisioned it.” Current agrees, saying “it’s not a total loss. There is much more to the space than its geometry. There is such a volume there, and intense calm.”

The other issue is the sunken, pea-gravel surface of the grove will have to be made handicapped-accessible. You wouldn’t just need ramps, but would have to compact the gravel for wheelchairs and the added pressure created “would kill the trees,” Shields says.

Shields has picked out 18 Locust trees of uniform age and height and would plant them in the two outer rows of root holes left, once the Kiley trees were removed. Locust trees, he says, work better in an urban environment than Chestnut trees. The exact replacement of half of the four rows, he says, would “resonate with Kiley’s work.”

Gould is unconvinced. Kiley’s vision “would be lost with Jim’s more open, flat and grassy alternative,” she says.

But landscape architecture, by its very nature, cannot last forever. Trees will eventually die and far faster in an urban environment. The famed Tuileries Garden has survived by cutting down the trees when they get old enough and replacing them with a new set of uniform age and appearance.

Ultimately this approach, rather than half measures like metal rods or cutting out the dying trees, might be the only to way permanently preserve Kiley’s vision. But that would be expensive, and doesn’t match the plan for the Marcus Center renovation, which is after all working with a building that is vastly different from the 1969 facility.

Shields served for years on the city’s Historic Preservation Commission, and notes that its charge is to save the integrity of historic structures. The commission can’t require the complete replacement of a structure and that might ultimately be required for the Kiley grove.

Bamberger muses that cities are much different places than 50 years ago. “The Kiley grove was ornamental. It was designed for its passive uses. It was a wonderful place to be alone.” But “that was before outdoor dining in Milwaukee, before people rode their bikes Downtown — or even walked for that matter. No one would design a place and a building like that today.”

Insiders expect the Historic Preservation Commission to rule that the grove must be saved, but the Common Council can consider other factors, such as economics, and could overrule that decision. Wherever you fall in the debate over the Kiley grove, the passion on both sides is a positive sign — of a city where design and urban issues are becoming increasingly more important.

Renderings

Shields’ Presentation on Building’s Compromised Integrity

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits, all detailed here.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

More about the Marcus Center redevelopment

- Eyes on Milwaukee: Marcus Center Unveils New Grounds - Jeramey Jannene - Nov 14th, 2022

- Eyes on Milwaukee: Marcus Center Starts Construction On Former Chestnut Grove - Jeramey Jannene - May 31st, 2022

- Plats and Parcels: Marcus Center Begins Redevelopment - Jeramey Jannene - Sep 20th, 2020

- Eyes on Milwaukee: Council Says Marcus Center Not Historic - Jeramey Jannene - May 7th, 2019

- Eyes on Milwaukee: Committee Says Marcus Center Isn’t Historic - Jeramey Jannene - Apr 30th, 2019

- Marcus Center Trees Removed Before Permit Issued - Jeramey Jannene - Apr 9th, 2019

- Eyes on Milwaukee: Marcus Center, Kiley Grove Deemed Historic - Jeramey Jannene - Apr 1st, 2019

- Murphy’s Law: Kiley’s Chestnut Grove Provokes Hot Debate - Bruce Murphy - Mar 7th, 2019

- Eyes on Milwaukee: Marcus Center Decision Delayed A Month - Jeramey Jannene - Mar 5th, 2019

- Eyes on Milwaukee: Marcus Center at a Crossroads - Jeramey Jannene - Mar 4th, 2019

Read more about Marcus Center redevelopment here

Murphy's Law

-

Top Health Care Exec Paid $25.7 Million

Dec 16th, 2025 by Bruce Murphy

Dec 16th, 2025 by Bruce Murphy

-

Milwaukee Mayor’s Power in Decline?

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Murphy

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Murphy

-

Total Cost of Foxconn Is Rising

Dec 8th, 2025 by Bruce Murphy

Dec 8th, 2025 by Bruce Murphy

Readers may benefit from reading 2 books about the vital importance of trees in all of our lives. One is fiction, The Overstory by Richard Powers. He is a well respected author who has garnered numerous awards if that is something that matters to you. In other words, he is not Donald Trump. The book traces the lives of 9 or 10 people who all share a significant relationship to trees. But the life of trees are the main subject of the book. Another book, nonfiction, which might interest people is The Hidden Life of Trees, What They Feel, How They Communicate by Peter Wohlleben. Warning, it could change your lives.

RE: “But landscape architecture, by its very nature, cannot last forever.”

Indeed, designed landscapes can be vulnerable to many threats, and change is a given. However, they do not have a defined “usable service life”–unlike roofs, many machines, or items “depreciated” for tax purposes. Lifespans of designed landscapes, like buildings, depend on how they are valued and maintained/preserved/restored. Thousands of designed landscapes remain significantly intact after hundreds of years. That includes many public urban landscapes.

Nonetheless, preserving landscapes does pose different challenges than buildings. The National Parks Services has specific guidelines for treating historic landscapes, whether designed or vernacular. https://www.nps.gov/tps/standards/four-treatments/landscape-guidelines/index.htm

Among national experts on landscape preservation are two emeritus University of Wisconsin professors (who taught in the School of Landscape Architecture). William Tishler’s many books include “Midwestern Landscape Architecture.” Arnold Alanen co-authored “Preserving Cultural Landscapes in America,” an early book exploring intersections of nature, culture and history. The first national meeting on that topic was held at The Clearing in Door County in 1979. The late Jens Jensen, who developed a distinctively Midwestern style of landscape architecture, designed The Clearing’s grounds. Formerly his home and a folk school, The Clearing has been continuously preserved and updated, in keeping with Jensen’s original designs.

Milwaukee has only a modest track record of intentionally preserving historic/cultural landscapes. However, it does have an exceptional roster of work by master landscape architects: Frederick Law Olmsted, Warren Manning, Horace Cleveland, Alfred Boerner, Dan Kiley, and Annette Hoyt Flanders (an all-but-forgotten Milwaukee native https://asteria.fivecolleges.edu/findaids/sophiasmith/mnsss245_bioghist.html), to name a few. Their local legacies convey varying degrees of historic integrity.

By virtue of their uniqueness and imbued sense of place, historic landscapes often attract tourism and other economic development. Many such places are public and thus more accessible to visitors than preserved buildings. Milwaukee certainly could capitalize on such assets and the rich narratives they embody–through thoughtful preservation and interpretation. https://shepherdexpress.com/news/features/spotlighting-historic-landscapes-could-benefit-milwaukee/