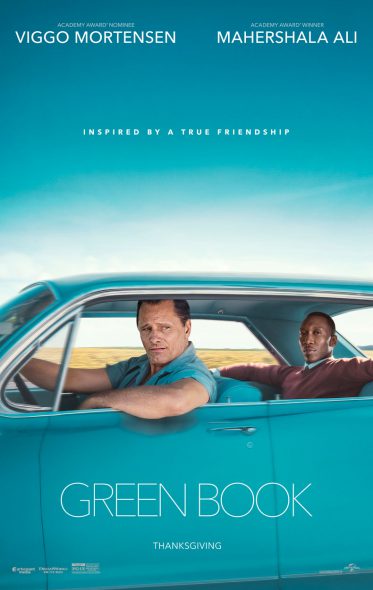

Despite Naysayers, ‘Green Book’ Is a Treat

Two great acting performances and the story’s often subtle about black-white divisions.

“Green Book,” a fine, funny yet thoughtful movie that deserves consideration in end of the year awards, seems to have run into an undeserved headwind.

The headwind is an attitude. In some circles and in parts of the black community some say they have no patience anymore, with those lessons from the past they regard as one-sided, made by whites mainly for whites. That’s how they view those little steps of understanding between blacks and whites in past decades, in what was and is so clearly a white supremacy society. In this view, it matters not the color of the film makers, but the interior bias of the studio system for which they work.

It was an issue unleashed in live theater terms in Shorewood over To Kill a Mockingbird onstage – is there any justification, even as a well-intentioned lesson, of having whites use the “n” word in dialogue? If white supremacy made the 1930s a racist time in America, who benefits by revisiting even the steps against that racism by whites who lived in that society?

Scholars go back to 19th century black thinker W.E.B. Du Bois discussing the “double consciousness” imposed on American blacks — “always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.”

Another way of saying it — what’s the value for a black audience of a white author pretending to be a child writing from her own perspective within a white supremacist society? Is a “literary relic” – as some describe Mockingbird — holding extreme sway over modern intellectual black thought? Aren’t those gains against racial slurs just a white dominant culture praising itself for bitsy steps forward?

The criticism has extended beyond Mockingbird (published in 1960) to a number of films from the 1960s such as A Patch of Blue ( Sidney Poitier becomes helpful to a blind white girl, who falls in love with him) and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? (white family struggles to embrace a black suitor — Poitier again), but also to more recent movies like A Time to Kill (jury’s eyes are opened when they mentally flip the skin color of the victim, and this one I also thought hard to swallow).

Yet it still seems all right for black films to mock the consequences of this white privilege past, as both Get Out (reviewed here) and Blackkklansman do, though the latter makes a big angry point about such racism continuing from on high in Donald Trump’s White House.

Green Book is intelligently done. It should rise in value as part of this social debate, largely because it is not what some critics have dismissively labeled the inverse of Driving Miss Daisy, this time the white chauffeur up front while the black man proudly pays for the back seat.

Not quite. It is based on a true story of a cosmopolitan, finicky black jazz and classical pianist, Don Shirley (and if you haven’t heard his playing, please take the time). He (as the movie quietly relates) took a pay cut from his normal elegant concert popularity in the early 1960s to tour the deep South to rich white folks, hoping to break through some established customs without having to be a black honky-tonk pianist with a jar for tips and a drink alongside.

So here comes this unlikely duo touring the Deep South by auto (the green book of the title is the Negro motorists’ guide to places in the South where blacks could eat and stay), with Tony Lip eager for money to send back to his wife and two kids in New York City and Shirley loath to speak to this hulking gangster type so prickly in his own right.

Director Peter Farrelly has combined his flair for comedy with a gift for interesting “on the road” scenarios. Shirley evokes a brilliant performance from Mahershala Ali as an aloof, lonely and even insultingly rigid genius of the keyboard restrained in manners and expression. He is so different from the blacks he encounters that the black milieu in the South doesn’t know how to deal with him. Until he sits down at a local bar’s piano and dazzles them with a bit of Chopin followed by boogie-woogie.

The music of the 1960s is almost a co-star. The film opens with a great Copa sequence that reveals a lot of Tony’s swaggering personality and familiarity with the nightclub and Mafia scene. There is a tremendous doubling of Shirley’s piano style that we think is Ali but is really the film’s composer, Kris Bowers.

Tony Lip is dumbfounded that Shirley, as great a player as he is, doesn’t know who Little Richard or Chubby Checker really are. He sarcastically suggests he is closer to black culture than the pianist is.

Shirley’s sad problems with drink and sex require Tony’s intercession while Tony’s temper requires Shirley to call in his good friend Bobby Kennedy. The whites in the South are almost uniformly painted as rednecks, a tendency in films that explore this period though without the tolerant affection you do pick up in movies from this period, like In the Heat of the Night. But the police up North have a sweet moment.

There are also subtle exchanges that force both men to confront the stereotypes they have inherited from their cultures. There’s an intriguing sequence when Dr. Shirley, so designated by his fellow musicians because of his academic degrees, abandons walking away and directly confronts a sophisticated Birmingham racist – putting Tony in the unusual role of calming presence.

The film is set in a particularly blatant time of open white privilege, but the racism is a framework for motivating and observing human behavior. There is something to learn from seeing how unusual representatives of their races find ways to reexamine themselves rather than let the racism of the times consume them.

There are a few moments when the lesson side of the movie proves a bit too obvious, but mostly the movie lets the events speak for themselves. Ali’s performance is fine tuned in every gesture and reaction. Mortensen is wonderfully rich and believable as Tony, whether consuming enormous quantities of food or accepting Shirley’s help in his letters home. Not nominated for anything, more’s the pity, is a warm and playful performance from Linda Cardellini as Tony’s wife.

Green Book is nominated for Best Movie, Mortensen for Best Actor and Ali for Supporting Actor.

Dominique Paul Noth, who also reviews theater for Urban Milwaukee, will be reviewing the top films up for Oscars this year.

Movies

-

Republican Legislators Push Tax Credits for Films Made in Wisconsin

May 21st, 2025 by Baylor Spears

May 21st, 2025 by Baylor Spears

-

Mystery Movie Being Filmed in Milwaukee With Kevin Spacey

Apr 24th, 2025 by Jeramey Jannene

Apr 24th, 2025 by Jeramey Jannene

-

Two Documentaries Offer Lessons in Fame

Apr 24th, 2025 by Dominique Paul Noth

Apr 24th, 2025 by Dominique Paul Noth

This was a comprehensive review of an excellent movie. The performances of Mortenson, Ali. and Cardinelli were magnificent. This film faced head-on issues of prejudice from a variety of perspectives.