Why Schimel’s Lawsuit Makes No Sense

Even conservatives suggest the AG’s suit against Affordable Care Act is bad law.

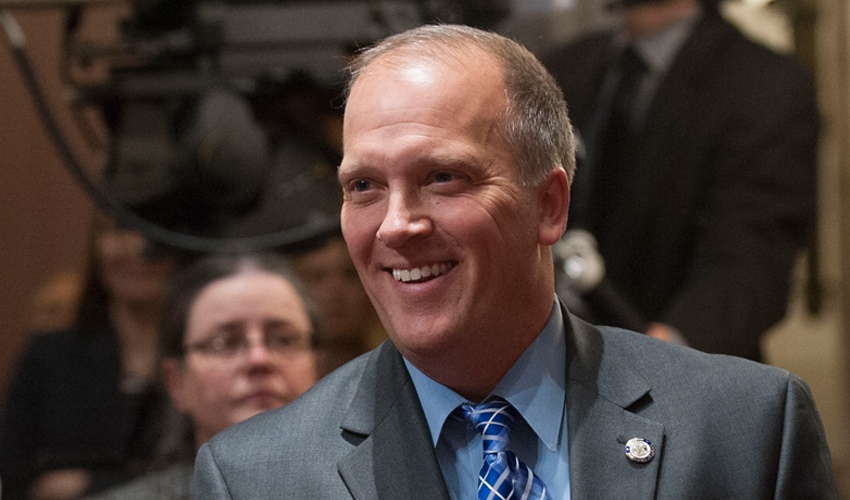

A lawsuit brought by a group of Republican Attorneys General, under the leadership of Texas AG Ken Paxton and Wisconsin AG Brad Schimel, has helped make health care a prime election issue. Called Texas v. the United States, the suit aims to strike down the whole Affordable Care Act or, at the least, the act’s prohibition on the ability of insurance companies to consider pre-existing conditions. It further serves as confirmation, if confirmation is needed, of Schimel’s conversion of Wisconsin’s Justice Department into an instrument of the Republican party.

Although 20 Republican-dominated states (or their governors) are listed among the plaintiffs, the dominant role was played by staff from Texas and Wisconsin. That is reflected by the many references to Wisconsin in the plaintiffs’ brief.

The plaintiff states’ argument boils down to three points:

- The US Supreme Court upheld the ACA’s individual mandate by treating it as a tax. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act set the tax to zero. A zero-dollar tax is no tax, making the mandate unconstitutional.

- The mandate was needed to support the guaranteed-issue and community-rating provisions in the ACA. Therefore, these “must be invalidated along with the individual mandate.”

- “The remainder of the ACA is non-severable from the individual mandate, meaning that the Act must be invalidated in whole.”

Each of these arguments has fatal flaws. On the first point, it is hard to see how something that was legal when it imposed a cost become illegal when it becomes costless. In essence, Congress converted the tax into a suggestion that people get health insurance. The government makes lots of recommendations.

But there is no need for the court to guess Congress’ intention. When Congress set the mandate to zero, it passed up the opportunity to remove the guaranteed-issue and community-rating provisions.

When Congress was considering eliminating the penalty upon people without have health insurance, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimated that removing the mandate would “increase the number of uninsured people by 4 million in 2019 and 13 million in 2027.”

It also estimated that average premiums in the nongroup market would be about 10 percent higher in most years “compared to CBO’s baseline projections. Those effects would occur mainly because healthier people would be less likely to obtain insurance and because, especially in the nongroup market, the resulting increases in premiums would cause more people to not purchase insurance.”

Thus, removing the penalty (actually setting it to zero dollars), which Congress proceeded to do as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, would increase both premiums and the number of people without health care insurance.

It would not, however, in the CBO’s opinion, cause the ACA to succomb to the much-feared “death spiral,” in which higher rates cause healthier people to drop coverage, leading to still higher premiums, further reducing enrollment, and so on, until the whole system collapses. Rather, the CBO concluded that “nongroup insurance markets would continue to be stable in almost all areas of the country throughout the coming decade.” Thus, Congress’ decision to reduce the mandate penalty to zero while leaving the pre-existing provisions intact was not irrational.

In an amici brief, five constitutional experts, including both supporters and opponents of the ACA, reacted with alarm to the plaintiff states’ suggestion that the court must invalidate other parts of the ACA:

The positions of the United States and the plaintiff States here get severability exactly backward. They disregard the clearly expressed intent of Congress and seek judicial invalidation of statutory provisions that Congress chose to leave intact. Accepting their invitation to rewrite the ACA under the guise of “severability” would usurp Congress’s role and inject incoherence into this critical area of law.

The plaintiff states’ third demand—that the court invalidate the whole ACA–makes no sense. The individual mandate affects only one part of the health care insurance market. The ACA includes many other provisions that stand or fall on their own, such as the expansion of Medicaid coverage and allowing children to stay on their parent’s insurance until age 25. The states’ brief makes no effort to justify the assertion that “the remainder of the ACA is non-severable from the individual mandate.” Even Donald Trump’s Justice Department did not buy that claim.

In a column for the Washington Post, the conservative jurist Michael McConnell describes Texas v. United States as “this dog of a case.” Writing in support of Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination to the Supreme Court, he describes Kavanaugh as “a good judge and a reasonable person. If he voted to accept the Texas argument, I would be gobsmacked.”

Yet Schimel and his co-plaintiffs may be counting on the increased politicization of the federal judiciary under the Trump Justice Department. Even if McConnell is right about Kavanaugh, if the case comes before other right-wing activist judges intent on imposing their own views on what is good public policy, perhaps the temptation to destroy part of the Obama legacy will be too strong to resist.

Early in his term, Brad Schimel impressed many observers when he came out against a scheme by Governor Walker and Republicans in the state legislature to drastically reduce the availability of government records under the open records law. Since then, however, it is hard to find examples of when he has put aside his partisanship. Instead he has turned the Justice Department into an agent of the Republican party.

Being an ideologue creates the danger of slipping into a bubble, in which only information (or people) supporting the ideology can slip through. In this environment, taking the lead in a lawsuit to challenge the ACA could seem like a good idea. Success in this lawsuit could help cement Schimel’s support of the right-wing base and donors.

It is likely that there was no one in Schimel’s inner circle who had the courage to point out that the majority of Wisconsin voters, including a majority of Republicans, support protections for people with pre-existing conditions. So, Schimel and his Republican peers in other states marched ahead and announced to the world that Republican politicians would leave people with pre-existing conditions to the mercy of the insurance companies.

This illustrates the dangers of what can happen when government officials view their prime role as advancing a partisan agenda.

Data Wonk

-

Why Absentee Ballot Drop Boxes Are Now Legal

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Imperial Legislature Is Shot Down

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

Counting the Lies By Trump

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

C’mon Bruce, you think that sensibility and outcomes for people matter to Schimel? It’s just a shameless grab for Koch money and Brownie points from the Federalist Society.

Had enough of this wasteful idiocy? Then vote Josh Kaul on Tuesday.

I second Jake’s comments on Schimel. A win by Kaul could retard the acceleration of idiocy in our once enlightened and progressive state.