Police Response Slow For Non-Violent Crimes

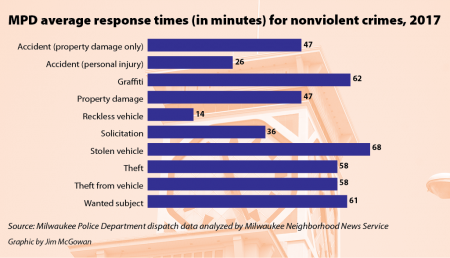

MPD response time averages 40 minutes for non-violent crimes, 68 minutes for auto theft.

South Side resident Dede Kupper and her husband Dan, a mechanic, woke up on a recent morning to find that their 2012 GMC Denali had been broken into and that thieves had stolen a bag containing $800 worth of tools. Kupper called the police, and after an hour of waiting, she called again.

“He [the police officer] told me it didn’t sound like $2,500 worth of stuff was stolen, which makes it a felony, so they weren’t going to send a squad. I told them I wanted one sent anyway,” she said.

Three hours later, Kupper said, an officer showed up.

“I don’t think they [police] considered it an issue but to us it was a big deal. Just because your life is not in danger, does that make it not worthy of a police response?” Kupper asked.

Her story is common in Milwaukee, where residents who report nonviolent crimes including stolen vehicles (68 minutes), theft (58 minutes) or theft from vehicle (58 minutes) face a long wait for a police response, if they respond at all, according to Milwaukee Police Department (MPD) dispatch data analyzed by Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service.

Margie Ramirez, who lives near West Greenfield Avenue, called 911 last summer after she heard a commotion in the street and looked out to see a woman ripping her clothes off, running in the street and throwing herself to the pavement.

“I thought she was going to get hit by a car,” Ramirez said. She waited an hour for police to arrive, and when they didn’t show up, called them back, she said.

“They said they had other calls to respond to and never came. I felt like they didn’t even care,” Ramirez said.

In general, police in Milwaukee were slow to respond to many violent and nonviolent crimes, according to an NNS analysis of more than 1 million MPD dispatch records that occurred during the five-year period between 2013 and 2017. The average response time by MPD for all types of calls was 33 minutes in 2017, down substantially from 65 minutes in 2015, but up slightly from 32 minutes in 2013. Calls for assistance from MPD are prioritized by the department to determine what calls get the quickest response, said Assistant Police Chief Ray Banks in an interview following a July meeting in the Amani neighborhood.

The priorities range from 1 to 6, with 1 being the highest priority.

The data shows average response times of more than 45 minutes for nonviolent crimes including property damage (47 minutes), reports of a wanted subject (61 minutes) and graffiti (62 minutes). These crimes might not be considered urgent, but nevertheless affect the quality of life of residents, according to Ald. Bob Donovan. Donovan described response times in general in the city as “dismal” and criticized the lack of action to improve them.

“We’re heading in the wrong direction,” he said. “What steps have been taken to address these deficiencies? I would argue that very little has been done to address these quality of life issues,” he said. MPD declined to comment for this story. Among the questions was why response times spiked dramatically in 2015.

Ald. Jose Perez said that he and other aldermen have been working with Paulina De Haan, emergency communications and policy director for the city of Milwaukee, to streamline the dispatch process and improve communication between residents and 911 dispatchers.

“Those jobs are tough, and we want to make sure the dispatcher is someone who understands the community and can communicate what information is needed to get a quicker response,” said Perez, during a July interview with NNS.

Tammy Rivera, executive director of Southside Organizing Committee, is part of a group working to shape a comprehensive plan to improve police policy and community relations. Photo by Edgar Mendez/NNS.

When that quick response doesn’t occur, it damages trust people have that police are responsive to their concerns, said Sharlen Moore, executive director of Urban Underground, a local youth-led social justice organization.

Tammy Rivera, executive director of Southside Organizing Committee said she consistently hears from community members that police take too long to respond to calls.

“I don’t have a scientific gauge of what an expected response time is, but I do know that many times I hear from the community that it’s been deemed unacceptably long,” she said.

Rivera said that while she believes that people — especially those who are victims of violence — expect an immediate police response, she knows that might not be possible. She also understands why people get upset when police don’t respond or take a long time to do so, including in cases involving property damage.

“It may be because someone’s tire got damaged, but these things can really impact someone’s life and sense of safety. If police don’t show up, then crimes like that end up being underreported because people think it’s not worth calling anymore,” Rivera said. Response times for property damage calls in the 53215 ZIP code, where her organization is located, averaged 41 minutes in 2017, down from 45 minutes in 2016.

Tom Schneider, executive director of COA Goldin Center, a nonprofit in the Amani neighborhood, said while it’s important to note that calls to police necessitate different responses, it is important that the community, as well as the police, work to reduce response times. “People have to be willing to make a call, which sometimes has to do with whether or not they feel the police will respond.”

Response times in Milwaukee are high for several reasons, according to city leaders and law enforcement representatives. They include a shortage of resources for law enforcement, flawed policing strategies that originated under former MPD Chief Ed Flynn, and a high number of crimes and criminals on the streets.

“The number of officers we have currently working our streets in Milwaukee is inadequate,” stated Donovan in an interview with NNS earlier this summer. MPD officers have faced increased peril this year, with two losing their lives in the line of duty since June. Residents have also been shaken by violence in the city, including 16 murders so far in August.

Milwaukee Police Chief Alfonso Morales addressed the violence during a recent news conference, where he outlined his ongoing plans to help stop the bloodshed and improve response times.

“I promised to send 100 officers back to the district by June 1 and accomplished that. This allows officers to be more proactive and respond more quickly,” Morales said. Morales also vowed to continue to hold community listening sessions and improve relations between residents and police, which he said was one of the keys to reducing violence in the city.

Mike Crivello, president of the Milwaukee Police Association, said he expected response times to drop under Morales due to his focus on improving relations with residents and the increase in neighborhood beat cops.

“When police have a smaller area to patrol they truly get to know those people, truly care and are able to respond better. They’re able to better crack down on these quality of life issues that impact residents,” Crivello said.

Still, he added, with limited manpower and high levels of crime, response times will suffer and residents such as Kupper will continue to be frustrated.

“If an action has been taken against me, be it a threat or vandalism, I deserve the attention of the police department as much as everyone else does,” Kupper said. “It’s not fair that … every little noise you hear makes you fearful because somebody might be stealing from you, and there is nothing that will be done about it if you don’t catch them yourself,” said Kupper, who added that she has a concealed carry permit.

Editor’s note: Sophie Bolich and Abby Ng contributed to this story. Matt Schumwinger, principal at Big Lake Data, provided data processing and geocoding.

This story was originally published by Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, where you can find other stories reporting on eighteen city neighborhoods in Milwaukee.

Political Contributions Tracker

Displaying political contributions between people mentioned in this story. Learn more.

- February 19, 2015 - José G. Pérez received $25 from Tammy L. Rivera