What Would Jane Jacobs Do?

10 takeaways from a visiting expert on the legendary urbanist.

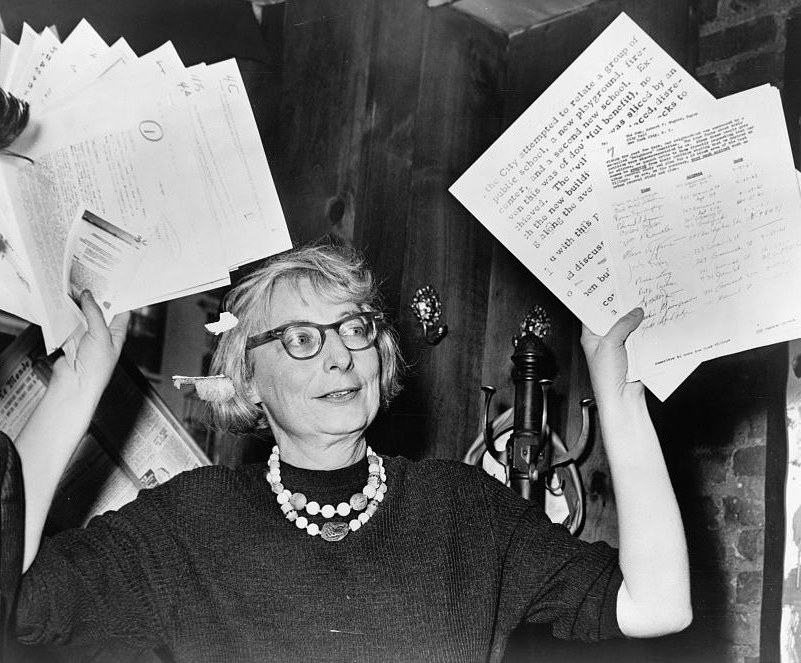

Legendary urbanist Jane Jacobs (1916-2006) promoted urban planning based on how people actually lived, “how cities work in real life”. Her once-renegade views are now widely espoused by urban planners and others who study cities. People in 240 cities worldwide also honor Jacobs by leading free “Jane’s Walks” to explore neighborhoods together and perhaps discover unseen aspects of their communities. Jane’s Walk MKE, an all-volunteer effort, expanded this year to include 35 citywide walks throughout May.

Visiting author Jamin Creed Rowan recently led a Jane’s Walk titled “What Would Jane Do?” through an East Side neighborhood, followed by a book talk at Boswell Book Company. Rowan said Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities changed his life. Published in 1961, the book helped Rowan make sense of his unexpected love of Boston after he moved there for graduate school in 1999. Growing up in a small farming community in California’s Central Valley, Rowan had initially learned to fear the “big cities of San Francisco and Oakland” located a few hours away, feeling panicky about “getting off at the wrong stop.”

Rowan’s chapter about Jacobs discusses factors that influenced her writings and clarifies some common misperceptions, including that her writings reflected mostly her experiences as a Greenwich Village resident. In fact, Jacobs’ had previously published many in-depth articles about New York’s business districts and immigrant settlement communities. In her work as an editor for Architectural Forum, Jacobs also traveled to many other cities. She was also among those who advocated, mostly unsuccessfully, for redesigning mid-century Manhattan public housing projects to maintain connections within their neighborhoods and opportunities for sociability.

Michael Carriere, an associate professor at Milwaukee School of Engineering who teaches courses on history, urban studies, and public policy, joined Rowan in leading the Jane’s Walk. The MSOE Honors Scholars program, which Carriere leads, hosted Rowan’s visit in conjunction with Jane’s Walk MKE and Boswell Book Company. Marquette University, UW-Milwaukee and ReciproCITY also co-sponsored.

Rowan and Carriere engaged 20-some participants in a spirited dialog about what seems to be working—or not working—from Downer to North Avenues and along streets in between. The following are 10 insights gleaned from that interactive walk and Rowan’s talk at Boswell Books about The Sociable City.

- People’s ideas about cities shape what they become—for better or worse. Rowan quoted Jacobs writing in Death and Life, “Private investments shape cities, but social ideas (and laws) shape private investment. First comes the image of what we want, then the machinery is adapted to turn out that image.” He noted that both public and private investments in cities are equally important and interdependent.

- Visual stimuli draw people to streets and keep them moving along them. The more doors, windows, and diverse options for activity are available and visible, the better an urban street functions, said Rowan, referencing a Jacobs truism. Ald. Nik Kovac, who attended the walk, noted that Whole Foods’ pending request to permanently close its North Avenue entrance is being debated at City Hall. Some believe that move would negatively impact the commercial corridor. Rowan himself now weighs in on such issues as a member of the City of Provo’s planning commission.

- Beware of what Jacobs called “border vacuum” structures. Rowan explained how some large buildings can drain life away from a street and make it difficult for adjacent spaces to succeed. He cited the massive, white parking structure on the east side of Downer Avenue’s business district (bordering Belleview Pl.). “Jane Jacobs would probably have organized and fought the development of this parking structure in this location,” he said. Walk participants lamented the fact that it got built despite much opposition, and has since gotten lackluster usage. Rowan noted that parking structures, if deemed necessary, are better placed just outside a business district.

- A slightly elevated space allows the sense of a “street performance.” Rowan said it is human nature for people enjoy watching other people. The patio of Stone Creek Coffee’s new cafe on Downer Avenue affords people watching with its two-step rise, said Rowan. “Permeable boundaries” along streets, such as outdoor cafes, encourage sociability and serve both patrons and passersby. He noted that some parts of Manhattan’s highly successful High Line, a park within a former elevated rail bed, offer such “theater seating.”

- Neighborhoods with both owner-occupied and rental housing often support more commercial activity. Jacobs wrote that a diverse population is desirable in terms of age and socioeconomic backgrounds, including residents, workers and tourists. That’s because people using the same street space at different times of the day, and for different purposes, is the most efficient and enlivening. Walk participants noted that several restaurants and the Downer Theater draw a late-night crowd, including many university students. Rowan and Carriere also sought insights about why numerous storefronts on Downer remain vacant in an area that seems a model location in terms of Jacobs’ theories. Participants noted issues involving a major property owner as well as challenges some businesses have faced in retaining a customer base and shifts in shopping patterns.

- Proximity within public spaces can engender positive “fellow-feelings.” Rowan explained that the term “fellow-feelings” has been written about since early in America’s history, as relating to urban life. However, the term originally referred to the type of sympathy that developed among people who knew each other well. He said the “tyranny of intimacy privileges the domestic realm and reinforces one standard of truth — that you can only be intimate or connected to people like you.” In contrast, he described views about “sociability” expressed by Jacobs and others who perceived the benefits of people interacting comfortably within urban spaces without being intimate.

- Vibrant public spaces promote a healthy “urban ecology.” Jacobs described people interacting in public spaces, including on sidewalks and streets and in stores, as “participating in unconscious cooperation.” Like many other midcentury urbanists, she had studied ecology–a science first popularized in the 1950s and ‘60s by Rachel Carson and others. Jacobs synthesized the language and logic of ecology in her ideas about urbanism. She observed that people function as part of an ecology of “mutual support” and believed that cities were extensions of, rather than separate from, the natural world, with their “intricate, living network of relationships.”

- Fellow-feelings can help facilitate civic ventures that serve everyone. Rowan said that investments in mass transit and public spaces, and adequate funding for schools, require that people value collective needs. He noted that public support for such civic infrastructure is more likely when people feel “emotionally attached to and ethically responsible for each other.”

- Building a more-robust narrative about “the commons” can counter-balance an emphasis on self-determinism. Rowan said that the need for people to deal with climate change could help to develop new narratives about the commons and collective solutions. “It will decrease the tolerance for seeking only individually oriented solutions,” said Rowan, whose current research relates to urbanism and climate change.

- Understanding the role of sociability is crucial to successful cities. Rowan wrote that “the publication of The Death and Life of Great American Cities signaled the consolidation and popularization of an urbanist discourse on sociability.” He also references other urban writers, including mid-century New Yorker journalists (Meyer Berger, A.J. Leibling, Joseph Mitchell and E.B. White) as well as memoirs, plays, novels, and museum exhibits. Nonetheless, Rowan looks more to the present and future than the past. He aims to “move a historically and conceptually rich conversation about urban fellow-feeling closer to the center of how we understand our urban past and the growing discussions about our planet’s urban future.”

Decisions about the kinds of cities people build are shaped by which interpersonal relations are deemed to matter. Rowan says understanding those beliefs will help decision makers become “more open to acknowledging the validity of new types of social arrangements that will inevitably continue to arise in cities, and more willing to modify the built environment to make room for them.”

Freelance journalist Virginia Small often writes about urbanist and design issues. She served on the all-volunteer Jane’s Walk MKE 2018 Organizing Committee.

Political Contributions Tracker

Displaying political contributions between people mentioned in this story. Learn more.

- May 7, 2015 - Nik Kovac received $25 from Virginia Small