Trickle Up Economics

The Great Recession’s huge impact on employment shows why trickle down doesn’t work.

Mr. Money Bags mural. Photo by aisletwentytwo. (CC BY 2.0)

It was popular, in some circles in the recent past, to relabel businesses as “job creators.” This phrase, which often preceded a proposal for some business subsidy, betrayed, in my view, a disturbing misconception of how a market economy works.

Every month, the National Federation of Independent Businesses surveys their members and reports an index of business confidence. In 2009 at the height of the Great Recession, the index hit a new low. The overall reason given by the surveyed businesses was weak demand. Yet, true to its ideological orientation, the business group opposed Obama administration efforts to inject funds into the economy.

Both the Great Depression and Great Recession resulted from a demand shortage, not a supply shortage. The collapse of demand fed upon itself: as consumers lost their jobs—or feared a job loss—they cut back on spending, resulting in a downward spiral of demand.

In her novel, Atlas Shrugged, Ayn Rand imagined a scenario in which the capitalists went on strike, causing a worldwide economic collapse. Assuming a market economy, Rand’s scenario seems highly unlikely. The disappearance of the capitalist’s products would represent opportunity for a new generation of entrepreneurs, so long as the demand was there.

Certainly, there have been supply collapses, including the Irish famines of the 19th Century, mass starvation in the Ukraine, China’s “Great Leap Forward,” and the present crisis in Venezuela. However, in each case, government action prevented the operation of a free market economy.

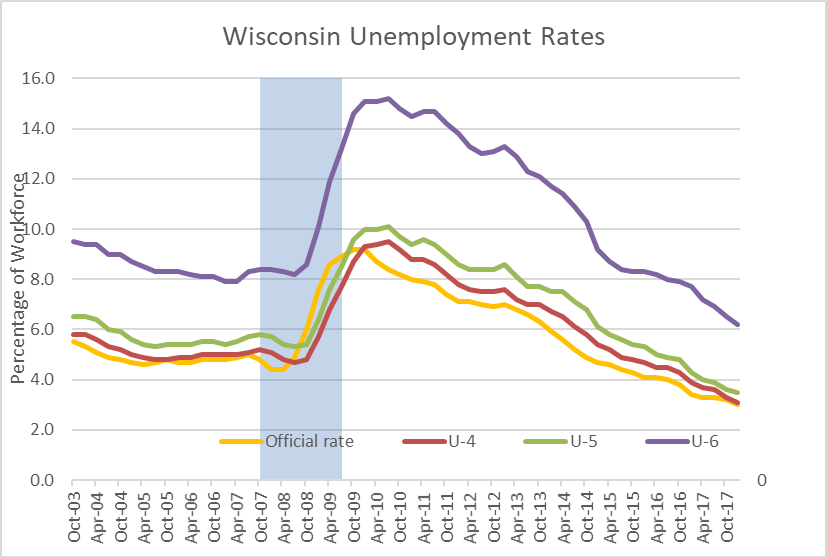

By contrast, a serious demand crisis takes a long time to resolve. The next chart shows Wisconsin’s unemployment rates through the first quarter of this year. The official rate, sometimes called “U-3,” is shown in yellow. It is calculated by taking the number of people who are unemployed and have searched for work in the prior 4 weeks and dividing that number by the total labor force.

The U-4 unemployment rate adds in “discouraged workers.” The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) defines discouraged workers as those who are not in the labor force, want and are available for work, and had looked for a job sometime in the prior 12 months. They are not counted as unemployed because they had not searched for work in the prior 4 weeks, for the specific reason that they believed no jobs were available to them.

The U-5 rate includes workers who wanted a job but had not searched in the prior 4 weeks citing any reason.

The U-6 rate adds in involuntary part-time workers, who are employed part time for economic reasons but want to work full time and are available to do so. For the past year, the involuntary part-timers have made up about 3 percent of the work force. (Between 2009 and 2011, it was 5 percent of the work force.)

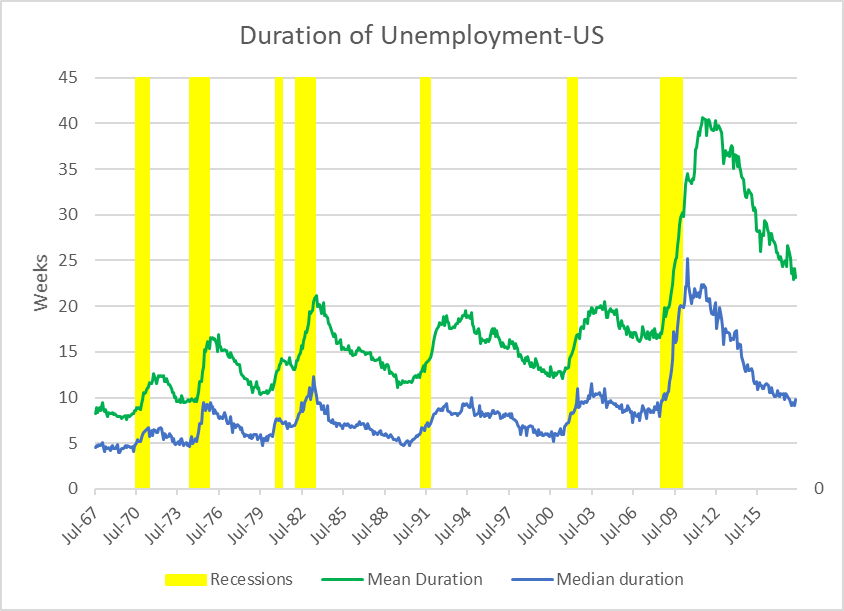

Duration of unemployment is another measure of the impact of episodes of joblessness. The next graph shows US “average” unemployment duration between 1967 and April 2018 using two measures of average: mean and median. The median is calculated by finding the center point: as many people have shorter periods of unemployment as have longer. The mean is calculated by adding up all the values and dividing by the number of episodes.

The fact that the duration’s mean (in green) is much larger than its median (in blue) indicates that there is a long “tail” of workers who’ve been unemployed for a long time and a larger number of job finders with very short spells of unemployment.

For many Americans, unemployment was far more devastating following the Great Recession than in earlier postwar recessions. The mean duration hit 40 weeks; even the median peaked at 25 weeks. Even today, with historically low official unemployment rates, the durations, using mean or median, are substantially higher than they were in past recoveries. In the most recent survey, half of jobless people found new jobs in ten weeks or less. For the other half, however, the job search may have stretched out to a year or more.

It is widely recognized that a market economy creates winners and losers. The people who find it hard to find another job or are stuck with part-time work when they want full-time are among the losers. Perhaps they are in the wrong place, have the wrong skills, or the victims of other factors. There is strong evidence that Donald Trump’s election was aided by support in places where voters felt left behind by changes in the economy.

One response to a changing economy is to erect fences to protect industries and jobs that are on the losing side. An example is the present administration’s plan to place tariffs on imports of steel and aluminum. This has raised concerns that tariffs will trigger a trade war as our trading partners, in turn, place tariffs on products they buy from the United States.

Or consider truck driving, one of the jobs that do not require a college degree. According to the BLS, “Employment of heavy and tractor-trailer truck drivers is projected to grow 6 percent from 2016 to 2026, about as fast as the average for all occupations. As the demand for goods increases, more truck drivers will be needed to keep supply chains moving.” But what happens to the demand for truck drivers if autonomous vehicles become widely used?

In the long run, history suggests that letting the free market operate freely benefits society. In the short run, however, it creates winners and losers. The winners are heavily skewed to the already wealthy who are positioned to make investments behind the changes.

Despite this, the theory behind “trickle down” policies, such as the recent Tax Cut and Jobs Act, is to subsidize the winners in the hope that some of that money will benefit the losers. This seems like a huge mistake to me.

It is a mistake economically because it does little to expand market demand. No business school that I know of teaches that investments or hiring should be made just because the business has extra money.

It is also a political mistake because by not addressing the problem of limited income security, it generates support for demagogues offering magical solutions like tariffs and wall-building.

This would suggest that advocates of trickle-down policies have it backwards. Instead of skewing it to give most of the benefits to business and the wealthy, the country would have benefitted from “trickle up” policies that strengthen the protections for those who lose out when a dynamic market forces changes.

Data Wonk

-

Why Absentee Ballot Drop Boxes Are Now Legal

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Imperial Legislature Is Shot Down

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

Counting the Lies By Trump

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Bruce, a lot of these trade deals need to be updated. Why must the United States be hollow out by lousy agreements. If a German wants an American vehicle its taxed at three times greater on the German who wants a Ford F 150 versus the American that wants a beetle. In China, you can not just open a business. you have to partner up with a Chinese firm and then your forced to give up intellectual property. These countries are not undeveloped countries that need a hand. They want to seize economic power.

Troll, you are completely right that tarrifs are generally bad. Raising them is bad for consumers and raising them is a bad way to try to fix unemployment. Of course, nobody but an economists wants to hear that the best way to increase demand is by training workers to be more productive. That’s wonkie. So, we get simple solutions based in circular reasoning and more tax cuts, which are trickle down. Trickle down doesn’t get to the unemployed. It doesn’t stimulate demand.

The straw man lives!

-No one put a gun to the heads of American businesses in the 1990’s when they went to China for cheap labor and gave up intellectual property etc. They were overcome by the pure greed for greater profit.

-Now even the most common products are ” Made in China ” . ( Pens / pencils / paper tablets plus almost everything sold at Target , Walgreens, Ace and Menards) .

With all of the profit margin why isn’t business hiring

Bruce need to tell that o China and some of the SAmerican countries that reduced poverty.