Is City Dragging Feet on Lead Filters?

Critics say yes; health department says it's done all it can without more funding.

An NSF/ANSI Standard 53 certified filter, installed on this faucet (filters also come in on-faucet and pitcher form), reduces lead exposure by 99 percent. Photo by Jabril Faraj.

A resolution passed by the Common Council on Nov. 28, which activists and aldermen have said will improve the city’s response to the lead poisoning crisis, would make Milwaukee a national leader in protecting people from lead exposure from drinking water, according to a national expert.

However, the Milwaukee Health Department has not issued updated guidance to its filter distribution partners and declined to answer questions about whether it plans to communicate the changes to the public.

“Milwaukee is not only being watched closely by advocates for safe water but I think it’s safe to assume that Milwaukee is being watched closely by other departments of health and other city governments,” said Yanna Lambrinidou, affiliate faculty at Virginia Tech University, founder of Parents for Nontoxic Alternatives and member of the Campaign for Lead Free Water. “There is no other city that I know of that is in this position.”

The resolution calls for the Health Department to include women of childbearing age (15-45) — along with pregnant and breastfeeding women and children under 6 — in the group that is most at risk for lead exposure and should be using a water filter. Its passage was the result of a months-long battle on the part of community advocates and health leaders, which Lambridinou said has been a typical path to moving lead-water policy forward in other cities, as well.

The resolution also expands the recommended age for testing children — up to age 6 — and directs the Health Department to update all its public communications related to drinking water safety.

Emmanuel Ngui, a professor of community and behavioral health promotion at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, applauded the changes in the new resolution. By including women of childbearing age, pregnant women and young children in the list of at-risk individuals, “you are closing the loop completely,” he said.

But he said he hopes health officials, care providers and activists won’t deliver this message strictly to women between the ages of 15 and 45. Ngui said any female who hasn’t yet reached menopause, including those under 15, should be educated on the risks of lead exposure.

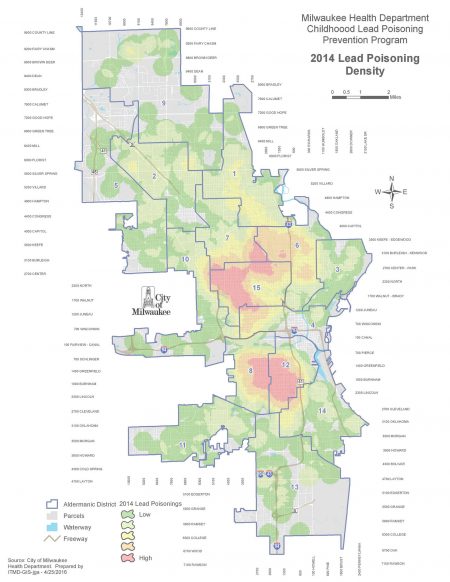

This 2014 map of Milwaukee shows the prevalence of lead poisoning cases by aldermanic district, with red areas having the highest density of cases. Map courtesy of the Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program.

MDH Director of Disease Control and Environmental Health Angela Hagy wrote in an email that the Health Department intends to continue educating people about the risks of lead in water, claiming the resolution “does not change the medical recommendations” relating to lead-testing guidance for care providers.

Hagy added, “While the resolution did not come with additional funding or staff, we are continuing to look at partnerships, outreach, and awareness efforts that we can expand or build upon,” noting the department “will continue to expand and enhance messaging and outreach to clinicians over the coming year.”

According to spokesperson Sarah DeRoo, during the last year the Health Department has attended events and community meetings, and advertised on “bus exteriors, bus shelters, billboards, and community websites” about the dangers of lead exposure.

DeRoo added that the Health Department’s filter distribution partners do not need additional guidance because “their clients are the at-risk populations.”

She added, “Therefore they do not have additional guidance other than to look up the addresses of their clients and distribute filters to those at properties with [lead service lines].”

Patricia McManus, president of the Black Health Coalition of Wisconsin and a member of the city’s Water Quality Task Force, said she has not been satisfied with the Health Department’s response to this issue. “It seems like there’s more arguments about not doing anything than to have a comprehensive plan,” she said. “When you don’t have a plan, then you plan to fail.”

Since the resolution’s passage, the Health Department has updated language on web pages focused on lead awareness and who is eligible for its Drinking Water Filter Program to reference “women who may become pregnant.” The Drinking Water Filter Program page provides a list of recommended filters (in English and Spanish) and explains how residents who cannot afford a filter can obtain one.

However, much of the city’s public messaging, on multiple pages on its website, does not acknowledge the change in the at-risk pool, or provide readily accessible information on the risks of lead and how best to protect oneself.

The Sixteenth Street Community Health Centers (SSCHC), in partnership with MHD, distributed about 800 filters to those with a lead service line during two months in late 2016; so far this year, SSCHC has distributed 362 filters to households with children under 6 or pregnant or breastfeeding women. The SSCHC Community Lead Outreach Program is based at its WIC clinic at 1337 S. Cesar E. Chavez Drive in the 12th Aldermanic District, which has 5,585 homes with lead service lines; the two adjacent near South Side districts include 15,813 homes with lead lines. According to Health Department data, District 12 has the highest concentration of lead poisoning cases on the South Side.

SSCHC Director of Environmental Health Kevin Engstrom said MHD has not provided any additional direction related to filter distribution since the resolution was passed. However, he said the resolution would not affect the organization’s lead efforts, which focus on children under 6.

“Through our lead outreach program we’re not working with women of childbearing age who don’t have children,” he said.

Alli Williams, 30, who rents the lower level of a home in Silver City, said she has known she has a lead line for about a year, since she checked a list of homes with lead service lines on the city’s website. At the time, Williams was the only one living in the unit and, despite doing some initial research into filters, she did not feel a sense of urgency at the time. “It just dropped off my mind,” she said.

After being told by a reporter about the risks of lead exposure and informed that they live in a unit with a lead line, about a third of the 19 residents interviewed for this story said they were interested in getting a filter. Not all of those interviewed are considered at risk, but many had members of at-risk groups, such as young grandchildren, visiting their home.

Lead poisoning can cause miscarriage, stillbirth and premature birth, and affect brain development in children. It also can cause long-term harm in adults, including increased risk of high blood pressure and kidney damage. Milwaukee Health Department officials have said lead paint is the primary source of lead exposure, but Lambrinidou disputes that claim. Soil can also be a source of lead exposure. Exactly how much different sources contribute to lead poisoning is unknown.

Engstrom and others agreed with McManus that the city must develop a plan, in partnership with community members, to identify priorities and determine a timeline for implementation. They agreed that the April 2017 Water Quality Task Force report, and the 20 recommendations that came out of that process, would be a good place to start.

In the meantime, Lambrinidou said the Health Department needs to strengthen official communications “to really deliver all of the facts,” so Milwaukee residents can adequately protect themselves. Ngui suggested the Health Department partner with schools, universities, physicians and religious institutions to reach women of childbearing age.

This story was originally published by Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, where you can find other stories reporting on eighteen city neighborhoods in Milwaukee.

More about the Lead Crisis

- MPS Plans Lead Remediation at 40 Schools This Summer - Evan Casey - Jun 27th, 2025

- Baldwin, Reed Demand Written Answers from RFK, Jr. on Firings of Childhood Lead Poisoning Experts at CDC - U.S. Sen. Tammy Baldwin - Jun 11th, 2025

- MPS’s LaFollette School Cleared of Lead Risks After Stabilization Work - Milwaukee Public Schools - Jun 11th, 2025

- Sen. Baldwin Hears From Parents About MPS Lead Crisis, Chides RFK Jr. - Evan Casey - Jun 9th, 2025

- Reps. Margaret Arney and Darrin Madison Urge Joint Finance Committee to Reinstate Essential Lead Abatement Funding - State Rep. Margaret Arney - Jun 5th, 2025

- Gov. Evers, DHS Continue Administration’s Efforts to Combat Lead Poisoning Statewide with Permanent Rule - Gov. Tony Evers - May 27th, 2025

- RFK Jr. Claims ‘Team’ Is In Milwaukee Helping With Lead Crisis, Health Department Can’t Find Them - Nick Rommel - May 22nd, 2025

- MPS Announces Starms Early Childhood Center Is Cleared of Lead Dangers - Milwaukee Public Schools - May 21st, 2025

- Milwaukee Has Removed 10,000 Lead Laterals - Graham Kilmer - May 13th, 2025

- New MPS Superintendent Cutting Central Office Jobs - Corrinne Hess - May 8th, 2025

Read more about Lead Crisis here