State’s Prison Costs Still Growing

Wisconsin has highest incarceration rate in Midwest, prison costs 12% higher than national average.

Waupun Correctional Institution. Photo by Lauren Furhmann of the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

A leading official in Governor Walker’s administration has said that the state will need to spend more money – soon – to expand the state’s prison capacity. State policymakers should take this opportunity to reform the state’s corrections system in a way that locks up fewer people, keeps costs down, and protects public safety.

An article in the Wisconsin State Journal describes the official’s statements:

“Growing by 35 inmates each month, the state prison system is out of room and will need more beds within three years, the head of the state’s corrections system said Thursday.

‘To be candid with you, we will need some relief and we will need it sooner than 2020,’ Department of Corrections Secretary Jon Litscher told lawmakers.”

Wisconsin’s prison population has increased dramatically in recent decades. The article notes:

“The state’s prison population has more than tripled in the last 25 years, according to DOC data. In 1990, there were 6,953 inmates in the state’s prisons. That number jumped to 20,000 by 2000, and spiked at a little more than 23,000 in 2007 before dropping over the following years. Since 2011, the population has been rising, to more than 23,000 at the end of 2016.”

As the prison population has exploded, so have the costs associated with the state’s corrections system. The state spent $1.2 billion on corrections services in 2017, more tax dollars than the state spent on the University of Wisconsin System. In fact, the state spends more tax dollars on the corrections system than any other purpose except K-12 education and health care for people with low incomes.

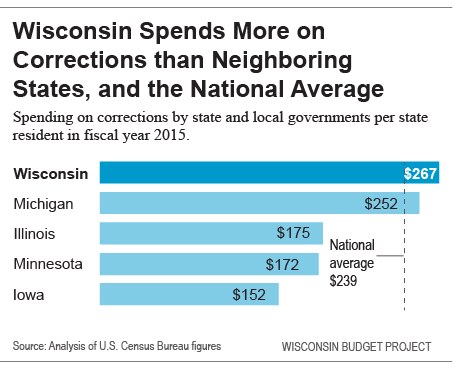

Wisconsin spends more on corrections than the national average – a sign that the state should be working to reduce corrections costs rather than increasing costs by expanding the prison population. Wisconsin state and local governments spent $1.5 billion on corrections in 2015. That’s over a tenth more — 12% — on corrections per state resident than the national average, according to U.S. Census Bureau figures. Nationally, only nine states spent more on corrections per state resident than Wisconsin. (Making useful comparisons of spending levels among states requires combining both state and local government spending, since various duties are performed at different levels of government in different states.)

Wisconsin state and local governments spend more on corrections than in the neighboring states of Michigan, Illinois, Minnesota, and Iowa. Wisconsin spends 6% more per state resident on corrections than Michigan, the neighboring state with the highest corrections costs, and 90% more on corrections per state resident than Iowa. If Wisconsin spent the same amount as Iowa on corrections per state resident, our state and local governments would spend $728 million less on corrections each year.

One of the reasons Wisconsin spends more per state resident than our neighboring states is that Wisconsin incarcerates a larger share of our population than our neighboring states. The cost of incarcerating an inmate in a Wisconsin medium security prison for one year is nearly $30,000 according to a recent estimate from the Wisconsin Department of Corrections.

Wisconsin has more people in prison or jail for our state size than Michigan, Illinois, Iowa, and Minnesota. Wisconsin incarcerates twiceas many people for our population size as Minnesota..

In addition to exacting a price from state taxpayers’ pocketbooks, Wisconsin’s costly overreliance on incarceration inflicts a great deal of damage on communities and families, particularly those of color. Wisconsin incarcerates a far higher share of African-American men than any other state, damaging families and individuals and keeping them from reaching their full potential. The consequences of high rates of incarceration harm the economic stability of families and weaken the state’s economy.

Fortunately, there are concrete steps Wisconsin can take to bring down the high monetary and community cost of its corrections policies – as long as state policymakers are willing to make fundamental reforms to the system instead of just adding new prison beds:

- Wisconsin can expand an approach with a proven track record of keeping people out of prison. Wisconsin’s Treatment Alternative and Diversions (TAD) program awards state grants to counties for programs that keep people with addiction and mental health issues out of jail and prison, and in effective treatment programs. Each dollar the state invests in the TAD program saves $1.96 in public costs by reducing incarceration and lowering the risk that offenders will commit new crimes – but these grants are not available in all counties at this point.

- Wisconsin can reduce the number of prison admissions that do not involve new convictions. Many people are sent to Wisconsin prisons because they violated a condition of their probation or parole, not because they are convicted of a new crime. The price tag for incarcerating people for rules violations adds up fast: Revocations for technical reasons that don’t stem from new convictions cost the state in the neighborhood of $140 million per year.

- Wisconsin can reduce recidivism by removing barriers to getting a job. Getting a job helps people leaving prison provide for their families and contribute to their communities, but obstacles can stand between people leaving incarceration and obtaining regular employment. The transitional job program provides employers with a temporary subsidy if they hire individuals with low incomes who meet certain criteria, thereby helping the individuals develop work-related skills they need to find employment on their own after the subsidy ends. Wisconsin’s current transitional job program is small, and should be expanded.

There is plenty of interest in conservative circles at the national level and in other states in looking at alternatives to incarceration as a way to bring down costs, but Wisconsin policymakers haven’t yet made it a priority. As lawmakers face the reality that Wisconsin prisons are already well past their intended capacity, and that locking up additional people will entail significant additional costs, perhaps they can be persuaded to implement the approaches that other states are using to save money and strengthen communities.

Wisconsin Budget

-

Charting The Racial Disparities In State’s Prisons

Nov 28th, 2021 by Tamarine Cornelius

Nov 28th, 2021 by Tamarine Cornelius

-

State’s $1 Billion Tax Cut Leaves Out 49% of Taxpayers

Sep 21st, 2021 by Tamarine Cornelius

Sep 21st, 2021 by Tamarine Cornelius

-

TANF Program Serves a Fraction of Poor Families

Aug 30th, 2021 by Jon Peacock

Aug 30th, 2021 by Jon Peacock

Hopefully, cost savings will not come through lowering food quality and other inhumane measures if economizing happens.

It is useful to put these costs into a social and political context, rather than just looking at the budget impact. It seems pretty clear that a critical group of Wisconsin voters believe that this is one area where they are getting their money’s worth for their hard earned tax dollars. This is the group of white, mostly suburban and rural voters who sometimes write comments to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel about the “animals” in the inner city, and who know all of the details about inner city social depravity, while telling us that they would never set foot in the violent city.

The reason that Wisconsin spends so much on incarceration is racial animus and a process of “otherization” that is more advanced than other places, in part because of a pattern of rigid segregation that has deep historic roots. As does the relationship of black people, especially black men, to the criminal justice system. As a young man, I was at first surprised to see how Police Chief Brier’s cops treated black people, after a childhood spent mostly on the all-white south side.

Then, as an intern with Milwaukee County government, I had the opportunity to witness trials in various courts. Two that stand out, even after many years, are Judge Coffey’s court, where white defendants got long sentences, and black defendants got really long sentences, and the court of the famous Judge Seraphim. For white defendants, Seraphim would generally say, “I’m going to give you a break this time, but I don’t want to see you back here. For black defendants, the pitch was, “I’m going to make an example of you,” or “I’m going to teach you a lesson.” Which he did.

In any place, patterns tend to become embedded in the culture, “the way we do things here,” and they are very hard to change. It makes it even harder when there is little interaction between groups, and the “others” become an abstraction, as in “African-American men” who stop being individuals with lives and a sense of self-awareness and become just a category.

Finally, there is the reality of high levels of crime in Milwaukee, and the related realities that there is no way to police or incarcerate your way out of them. On the “back end,” the article mentions the “transitional jobs program,” a good, but incomplete idea. For a significant number of individuals being released from prison, there is a need for far more than a job. In some cases, these men (and some women) do not understand what it means to work and have a job. They are also dealing with behavioral health issues, undiagnosed and made worse in prison, and have been disconnected from their families. The most ambitious – and effective – initiative in the country for dealing with these issues in a comprehensive way is “Better Futures” in the State of Minnesota.

In the end, the voters who control state government must see the benefit in going in a different direction, and that government must be willing to take on the powerful forces that see prisons as a jobs program and economic engine in rural areas. It is doubtful, especially in an administration that skillfully uses racial animus toward its own ends, that this is going to happen, whatever the budget impact.

Another election item to talk up! Great critical review. Thanks!