US Supreme Court Wrong on Redistricting?

By focusing only on racial gerrymandering justices miss the bigger picture.

![How to Steal an election. Image by Steven Nass (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://urbanmilwaukee.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/How_to_Steal_an_Election_-_Gerrymanderingj.jpg)

How to Steal an election. Image by Steven Nass (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.

Let’s start our exploration with the North Carolina decision. It was written by Justice Kagan, with Justices Thomas, Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sotomayor joining. Justice Alito wrote an opinion dissenting from part of Justice Kagan’s decision. He was joined by Justices Roberts and Kennedy. Justice Gorsuch entered the court too late to participate.

The case involved two Congressional districts, Districts 1 and 12, that for years sent African Americans to Congress. This was true even though blacks were under 50 percent of the voting population in each district. Each was a “crossover district” in which black candidates were able to attract enough white votes to win. In its most recent redistricting plan, the North Carolina legislature changed each district’s boundaries so that over half the voters were black.

Under the federal Voting Rights Act a state may not use race as the predominant factor in drawing district lines unless it has a compelling reason. A three-judge district court ruled that the changes were motivated by race. By packing more blacks into these two districts, black voters would have less influence in other districts.

In his partial dissent, Alito disagrees with Kagan when it comes to District 12. He argues that the redesign of District 12 was motivated by partisan considerations. By placing more Democrats (who happened to be black) into District 12, the legislature made other districts more safe for Republican candidates.

Alito disposes of District 1 in a footnote: “I concur in the judgment of the Court regarding Congressional District 1. The State concedes that the district was intentionally created as a majority-minority district.”

Unlike North Carolina, where racially-motivated gerrymandering and partisan-motivated gerrymandering converge, there is no question that Wisconsin’s Act 43 was motivated by a desire to entrench Republican control of the state legislature. The Supreme Court decisions on partisan gerrymandering offer a frustrating tale of mixed messages and indecisiveness.

In 1986, writing for the court (Bandemer), Justice White held “that political gerrymandering … is properly justiciable under the Equal Protection Clause.” However, he ruled against those challenging Indiana’s redistricting because he wasn’t convinced the evidence was strong enough.

Almost twenty years later, in Vieth (2004), the Supreme Court tackled the subject again. The decision’s Syllabus summarizes the result:

After Pennsylvania’s General Assembly adopted a congressional redistricting plan, plaintiffs-appellants sued to enjoin the plan’s implementation, alleging … that it constituted a political gerrymander in violation of Article I and the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. The three-judge District Court dismissed the gerrymandering claim, and the plaintiffs appealed. … Justice Scalia, joined by the Chief Justice [Rehnquist], Justice O’Connor, and Justice Thomas, concluded that political gerrymandering claims are nonjusticiable because no judicially discernible and manageable standards for adjudicating such claims exist. They would therefore overrule Davis v. Bandemer, … in which this Court held that political gerrymandering claims are justiciable, but could not agree upon a standard for assessing political gerrymandering claims.

The Syllabus goes on to describe Justice Kennedy’s position: “That a workable standard for measuring a gerrymander’s burden on representational rights has not yet emerged does not mean that none will emerge in the future.”

Two years later, in League of United Latin Am. Citizens v. Perry (LULAC) (2006), the first mention of “symmetry” appears. The decision was triggered by Republican decision, when they gained control in Texas, to redistrict the legislature and US House seats to give themselves a further advantage.

In the decision by Kennedy, he noted a proposed symmetry standard that would measure a map’s bias by “the extent to which a majority party would fare better than the minority party should their respective shares of the vote reverse.” He makes two criticisms of this standard: that it might “depend on conjecture about where possible vote-switchers will reside” and the need for “providing a standard for deciding how much partisan dominance is too much.”

He concludes “without altogether discounting its utility in redistricting planning and litigation, we conclude asymmetry alone is not a reliable measure of unconstitutional partisanship.” Thus he leaves the door open to a more fully developed symmetry standard.

By contrast, Scalia (with Thomas) tries to firmly slam the door shut:

Unfortunately, the opinion then concludes that the appellants have failed to state a claim as to political gerrymandering, without ever articulating what the elements of such a claim consist of. That is not an available disposition of this appeal. We must either conclude that the claim is nonjusticiable and dismiss it, or else set forth a standard and measure appellant’s claim against it. … Instead, we again dispose of this claim in a way that provides no guidance to lower-court appellants’ claims as nonjusticiable.

This strikes me as equivalent to saying that because we have not found a cure for a disease, we should declare it incurable and stop looking. Scalia goes on to lament that the decision “provides no guidance to lower-court judges.” Rather than Scalia’s top-down model, I think the court would be well-advised to encourage the lower courts to examine a variety of ways to measure asymmetry.

Somewhat surprisingly, Chief Justice Roberts (with Alito) expresses neutrality to the question as to whether a standard can emerge:

… I agree with the determination that appellants have not provided “a reliable standard for identifying unconstitutional political gerrymanders.” … The question whether any such standard exists—that is, whether a challenge to a political gerrymander presents a justiciable case or controversy—has not been argued in these cases. I therefore take no position on that question, which has divided the Court …

Asymmetry can be measured a number of different ways and it is probably foolish to think that there is a single perfect measure. If one measure shows extreme partisan symmetry it is likely others will as well. For Wisconsin’s Act 43, efficiency, the difference between the median and mean populations of districts, and projections of outcomes at different voting percentages all point to extreme asymmetry favoring Republicans.

Since Wisconsin elections cluster around 50 percent for both parties, directly testing asymmetry requires very little conjecture. Since Act 43 took effect, there have been three state-wide partisan elections–the presidential elections in 2012 and 2016 and the gubernatorial election in 2014. Among them they likely range of Wisconsin election results: Democrats up 7 percentage points (2012), Republicans up by 6 (2014), and almost tied (2016). Despite these differences the three elections tell a very consistent story about asymmetry. Kennedy’s concern about “conjecture about where … vote-switchers reside” is much more relevant to state where one party dominates than competitive states like Wisconsin.

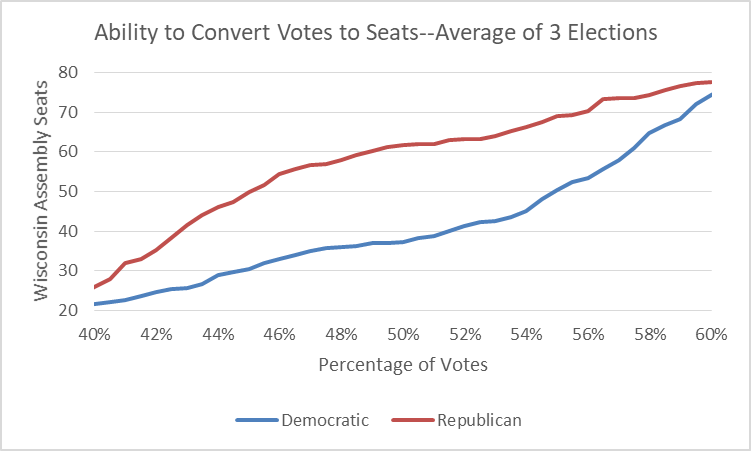

The next graph shows the predicted results for Republicans and Democrats depending on their vote percentages. Particularly in the 45 to 55 percent range, where Wisconsin elections usually end up, Republicans enjoy an enormous advantage.

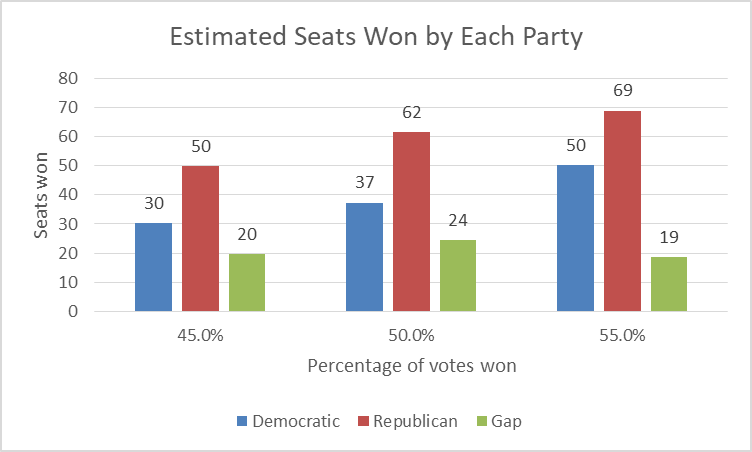

The next chart spells out this advantage in numbers. If Republicans gain half the vote, they can expect to win 62 seats; by comparison, Democrats can expect 37 if winning half the votes. At a 95 percent confidence level, the margin of error is 6 seats, far less than the Republican-favoring gap produced by Act 43.

The justices evince a deep fear that by ruling against partisan gerrymanders they will insert the courts into partisan battles. However, by making racial gerrymanders far easier to challenge than partisan ones, they have created the very situation they fear. In the south the two types look very much the same, so the courts are forced to read the motivations of the sponsors.

Apparently the current litigation is at least the fourth time that North Carolina’s District 12 has come before the Supreme Court. In the previous decision (Easley v. Cromartie), the Supreme Court reversed a lower court decision against the district boundaries, ruling that the “District Court’s conclusion that the State violated the Equal Protection Clause in drawing the 1997 boundaries is based on clearly erroneous findings.”

While very similar, the two cases have two striking differences: (1) the 1998 boundaries were set by Democrats; today’s by Republicans, and (2) there was almost a complete switch in those justices voting to uphold the boundaries and those voting to overturn them. In the earlier decision, justices voting to uphold the districts were Breyer (Author), Stevens, O’Connor, Souter, and Ginsburg. The dissent consisted of Thomas (Author), Rehnquist, Scalia, and Kennedy. In other words, except for Thomas, the so-called liberal and conservative camps traded positions on whether or not a redistricting plan was or was not motivated by race.

By refusing to rule against partisan motivated gerrymandering while often rejecting racial gerrymanders, the Supreme Court has turned its back on a charge that can be evaluated quantitatively—whether a redistricting plan creates unacceptable asymmetry—to one likely to be a matter of opinion—whether a gerrymander was motivated by considerations of race or partisan advantage. In doing so, the court has plunged itself into the very morass it was trying to avoid.

More about the Gerrymandering of Legislative Districts

- Without Gerrymander, Democrats Flip 14 Legislative Seats - Jack Kelly, Hallie Claflin and Matthew DeFour - Nov 8th, 2024

- Op Ed: Democrats Optimistic About New Voting Maps - Ruth Conniff - Feb 27th, 2024

- The State of Politics: Parties Seek New Candidates in New Districts - Steven Walters - Feb 26th, 2024

- Rep. Myers Issues Statement Regarding Fair Legislative Maps - State Rep. LaKeshia Myers - Feb 19th, 2024

- Statement on Legislative Maps Being Signed into Law - Wisconsin Assembly Speaker Robin Vos - Feb 19th, 2024

- Pocan Reacts to Newly Signed Wisconsin Legislative Maps - U.S. Rep. Mark Pocan - Feb 19th, 2024

- Evers Signs Legislative Maps Into Law, Ending Court Fight - Rich Kremer - Feb 19th, 2024

- Senator Hesselbein Statement: After More than a Decade of Political Gerrymanders, Fair Maps are Signed into Law in Wisconsin - State Senate Democratic Leader Dianne Hesselbein - Feb 19th, 2024

- Wisconsin Democrats on Enactment of New Legislative Maps - Democratic Party of Wisconsin - Feb 19th, 2024

- Governor Evers Signs New Legislative Maps to Replace Unconstitutional GOP Maps - A Better Wisconsin Together - Feb 19th, 2024

Read more about Gerrymandering of Legislative Districts here

Data Wonk

-

Why Absentee Ballot Drop Boxes Are Now Legal

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Imperial Legislature Is Shot Down

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

Counting the Lies By Trump

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

You touched on a lot of important subjects, but my two favorites were:

1) the abuse of the idea of getting African Americans in congress, used to politically gerrymander against their very interests. “Sure we can have more of you in congress, but as a trade we’ll have less democrats there.” Which is why the African American voter actually care about – party, not race. Blacks vote along party lines, not racial ones.

B) the importance of the idea of partisan symmetry and it’s viability as an official standard.