Study Shows Poverty’s Impact on Kids

New UW study shows 20% of test scores deficit due to lags in early brain development.

Stress adds to school woes

While researchers now can point to poverty as a cause of developmental brain delays, they do not know what specifically about poverty is changing children’s brains. Pollak theorized it could be the “pervading sense of stress” that can accompany poverty.

The prolonged activation of stress response systems, known as toxic stress, in a child without the buffer of a stable environment can disrupt brain development and cause other harmful consequences such as increased risk for disease into adulthood, he said.

University of Wisconsin-Madison psychology professor Seth Pollak has conducted research showing that poverty can have biological effects long before children enter the classroom. Photo by Bridgit Bowden of Wisconsin Public Radio.

“It’s that whole atmosphere that is contributing to the way kids sleep, to the stress level, or the regulation level of the way they digest food and the way that they grow,” Pollak said. “And that whole environment taken together, that it is poverty, and that’s what is actually affecting central nervous system development.”

So-called adverse childhood experiences can rewire a child’s brain in a way that makes it harder to learn, Dr. Bruce Perry told a group of Wisconsin juvenile court and child welfare officials meeting in Wisconsin Dells last fall.

Perry, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Northwestern University, emphasized that not all stress is bad.

“Stress is what helps you develop. Stress makes you a better musician. Stress makes you a better athlete,” Perry said. “Stress makes you better. It is the pattern of stress that makes all the difference.”

He explained that if the stress is “moderate” and “controllable,” children can develop successful mechanisms for responding to future, unexpected stresses. But other kinds of stress caused by factors such as violence or neglect in the home can create a state of alarm that makes children more reactive, often described as the fight, flight or freeze response.

When presented with new material in school, for example, such children may have a hard time activating the thinking part of the brain.

“If you are a child who is dysregulated, and you are introduced to the very same challenge that the rest of the class is, you are so overwhelmed that you shut down your cortex completely and your cortex is unable to actually process information,” Perry said.

“And in order to master the same content, you are required to have 10 times the repetition, which is not going to be provided in the typical classroom environment, and you’re going to fall further behind.”

Parent, child brains linked

Not only are children’s brains more malleable in early childhood, the brains of new parents are also subject to change, according to a June 2015 study from the Aspen Institute, an education and policy studies nonprofit organization based in Washington, D.C.

New mothers and fathers experienced structural changes during the first few months after their children’s birth, according to the report, as their newborns’ brains are also developing — emphasizing a need for a two-generation approach to early intervention.

Dr. Dipesh Navsaria, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, is the medical director of the Wisconsin branch of the national Reach Out and Read program. Photo by Coburn Dukehart of the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

“True two-generation interventions don’t say … the parent is just a route to making the child’s life better,” said Dipesh Navsaria, a UW-Madison associate professor of pediatrics, who was not involved in the study. “The parent and the child both have inherent value, and we should be investing in them both because … that’s where we get an added effect.”

Pollak explained that human brains develop structurally in an inside-out pattern. The frontal lobe behind the forehead controls behavior and attention — skills children need in school — and it develops later.

“Because those parts of the brain are very late developing, they might be very vulnerable … because they’re growing a lot while children are encountering or not encountering things in the world,” Pollak said.

Children’s brains are in a constant state of growth, or plasticity, and they can tolerate a number of adverse experiences before long-term effects are seen, Pollak said. That resiliency means some effects can be reversed.

“It’s just a question of what’s the cost of waiting longer and longer before we do something,” Pollak said.

As Navsaria explained, it is more difficult to address a speech delay in an 8-year-old than a 3-year-old, and in a 3-year-old than an 18-month-old.

“The upshot of this is that you have this fantastic opportunity in the first five years of life to wire things right, or if they’re not wired right, to do remediation,” Navsaria said. “If we get it right early on, then we have a better likelihood of a good outcome.”

Reading gateway to learning

Navsaria is also the medical director of the Wisconsin branch of the national Reach Out and Read program, which was examined as part of an October 2015 Aspen Institute report. There are about 160 Reach Out and Read programs and 50 clinics in training in Wisconsin.

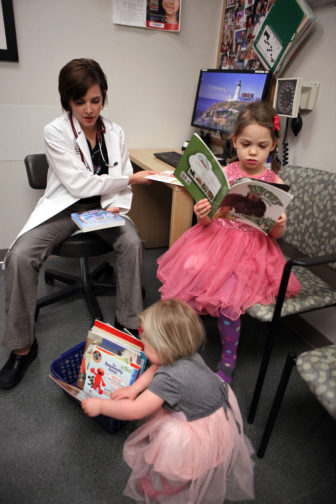

Francesca Vash, a nurse practitioner at Group Health Cooperative health care center in Madison interacts with her patients Naja Tunney, 5, and her sister Hannah, 2, during a check-up. GHC participates in the national Reach Out and Read program, which distributes distributes books to children up to age 5 at each regular check-up. Photo by Coburn Dukehart of the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

The program distributes one book per well-child visit from ages six months to 5 years, for a total of 10 visits. The program costs about $20 per child, said Brian Gallagher, executive director of the national organization based in Boston. Clinics pay for the program through fundraisers, grants or by including it in their budget.

Francesca Vash, a nurse practitioner at Group Health Cooperative’s Capitol Clinic in Madison, said her patient population includes families who are transient or homeless with little access to books.

“No matter the age of the child, I always talk about the importance of reading,” Vash said.

By intervening through the health care system, Navsaria said, medical professionals can keep track of children’s development and model reading techniques to parents in a consistent manner.

“I think it changes how people think about (achievement gaps) — that it could be any one of us and it isn’t a moral failing, this isn’t some sort of irresponsibility, this is the effects of children’s brains being under siege,” Navsaria said.

‘Human capital being wasted’

Some experts say early interventions also are more cost-effective than remedial programs in adolescence and early adulthood.

University of Chicago economist James Heckman found it is cheaper to pay for high quality preschool than later interventions such as hiring teachers to create low student-to-teacher ratios, government-funded job training or rehabilitation programs for ex-convicts.

Heckman’s analysis of low-income African-American children who attended the High/Scope Perry Preschool Program in Ypsilanti, Michigan, during the 1960s found that every $1 invested returned about $7 to $12 back to society.

Investing in programs aimed at older individuals is still beneficial, he wrote, although the return is lower.

“Investing in disadvantaged young children is a rare public policy initiative that promotes fairness and social justice and at the same time promotes productivity in the economy and in society at large,” Heckman wrote.

Pollak said such research shows the “human cost to the human capital being wasted.”

Bipartisan effort to combat poverty

Ed Hubbard, an assistant professor of educational psychology and the director of the Educational Neuroscience Lab at UW-Madison, said Pollak’s research should serve as ammunition for policy changes for Republican and Democratic legislators alike.

“These types of data put the ball squarely back in the politicians’ court,” Hubbard said.

That appears to be happening in Wisconsin. State Sen. Julie Lassa, D-Stevens Point, and Rep. Joan Ballweg, R-Markesan, kicked off the bipartisan Legislative Children’s Caucus in April.

State Rep. Joan Ballweg, R-Markesan, and state Sen. Julie Lassa, D-Stevens Point, speak at meeting of the bipartisan Legislative Children’s Caucus in Madison in April. Members formed the group to push for policies that benefit Wisconsin’s children. Photo by Coburn Dukehart of the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

Lassa said the goal is to advocate for evidence-based public policies that will benefit the state’s children.

To Lassa, Pollak’s research provides proof that poverty harms children.

“To me, there shouldn’t be any more arguing about the science,” Lassa said.

“I think all together the work that (Pollak) is doing is helping us to bring awareness to the necessity to do more comprehensive help when it comes to children,” Ballweg added.

The lawmakers said helping children could have long-term economic benefits.

Said Lassa: “These children are our future workforce, they’re our future leaders. … We need to be making sure that they get the best start possible.”

Cap Times reporter Abigail Becker wrote this story while working as an intern at the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism. Wisconsin Public Radio reporter Bridgit Bowden and Center Managing Editor Dee J. Hall contributed to this report. The nonprofit Center (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Article Continues - Pages: 1 2

Children Left Behind

-

Teaching Poor Kids Where They Live

Feb 18th, 2016 by Abigail Becker

Feb 18th, 2016 by Abigail Becker

-

Wisconsin Going Backwards on Achievement Gap

Dec 21st, 2015 by Abigail Becker

Dec 21st, 2015 by Abigail Becker

-

State Has Worst Black-White Learning Gap

Dec 19th, 2015 by Abigail Becker

Dec 19th, 2015 by Abigail Becker