Caperton Rule Could Kill John Doe Decision

State high court’s Doe ruling runs afoul of U.S. Supreme Court decision on judicial conflicts.

Parties objecting to the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s decision to shut down the John Doe investigation of coordination between the Scott Walker campaign and conservative advocacy groups have until April 29 to file their appeal with the U.S. Supreme Court. There are two obvious issues. The first is the conflict between the two courts’ decisions relating to coordination, which I discussed in my last column. The second is a lack of concern among the four state justices in the majority about the obvious conflicts interest arising from the huge spending in support of their elections by some of the very organizations who were targets of the John Doe investigation.

The U.S. Supreme Court has long held that judges should recuse themselves whenever their financial interests put their independence in doubt. As the American Bar Association put it, “The integrity of the judicial process requires that judges avoid both actual bias and the reasonable appearance of bias so as to preserve confidence in the fairness and impartiality of judicial determinations.” The first time the U.S. Supreme Court considered the impact of substantial political contributions on a judge’s independence was its 2009 decision in Caperton v. Massey.

This case involved a lawsuit against the Massey coal company by Harman Mining Company president Hugh Caperton in which a jury awarded $50 million to him. Following this, Don Blankenship, the president of Massey Coal, donated $3 million to help elect Brent Benjamin to the West Virginia Supreme Court. After defeating the incumbent in a close election and despite what most people would consider a serious conflict, Justice Benjamin refused to recuse himself and voted in favor of Massey Coal to overturn the jury’s decision.

In an appeal on a writ of certiorari, the U.S. Supreme Court voted 5-4 that Justice Benjamin was required to recuse himself because “there is a serious risk of actual bias.” The decision, written by Justice Anthony Kennedy continued:

The inquiry centers on the contribution’s relative size in comparison to the total amount of money contributed to the campaign, the total amount spent in the election, and the apparent effect such contribution had on the outcome of the election.

This decision was greeted with relief by many people concerned about the ability of campaign money to distort justice. Ted Olson, formerly Solicitor General in the Bush administration and counsel for the petitioners, argued that: “The improper appearance created by money in judicial elections is one of the most important issues facing our judicial system today.”

Interest in this outcome was reflected by the large number of amici briefs submitted arguing that Justice Benjamin should have recused himself. A number came from organizations with a history of concern about the role of campaign contributions in corrupting the courts, such as the Brennan Center for Justice, the Justice at Stake Campaign (with support from 27 government reform groups), and various legal association including the American Bar Association.

More surprising, perhaps was a brief joined by several large corporations—Intel, Lockheed Martin, Pepsico, and Wal-mart. Pointing to a number of polls, this group argued that litigants, judges, and the general public all believe that campaign contributions influence judicial decision making. For American business, the possibility that outcomes would be influenced by campaign contributions made it more difficult to “assess risks and calibrate benefits,” their brief noted.

If the U.S. Supreme Court decides to consider the writ of certiorari appealing the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s decision it would be only the second time it has considered campaign spending as an issue affecting judicial independence. While there are differences between the two cases there are striking parallels.

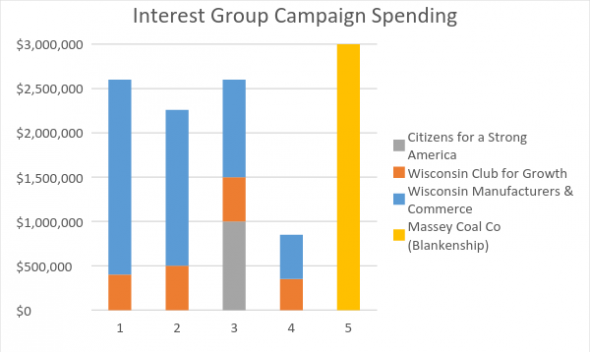

The amount of money donated to any one of the justices is the same order of magnitude, as shown in the chart to the right. In aggregate, the four Wisconsin Supreme Court justices who voted to shut down the John Doe investigation received much more support from organizations that collaborated with the Walker campaign than Justice Benjamin received from Blankenship, according to estimates from the Wisconsin Democracy Campaign.

In his dissent from the Caperton decision, Justice Roberts criticized his colleagues for providing “no guidance to judges and litigants about when recusal will be constitutionally required.” The ABA would remedy this by proposing that all states adopt a rule requiring disqualification when a “judge knows or learns by means of a timely motion that a party, a party’s lawyer or the law firm of a party’s lawyer has within” a set number of years given aggregate contributions totaling a specified amount.

In 2009, the Wisconsin Supreme Court, by a 4-3 vote, rejected a rule proposed by the League of Women Voters and former Justice Bill Bablitch that donations or other campaign support of at least $1,000 should trigger recusal. Perhaps not coincidentally, the four judges voting to reject the rule were the same group voting to shut down the Doe II probe.

It is hard to see that, at a minimum, the four state justices would not have felt some gratitude for the aid these organizations had given them. That gratitude is plainly evident in Justice David Prosser’s statement on why he did not recuse himself, where he makes clear he couldn’t have been elected without support from groups like Wisconsin Manufacturers. And the language in the court’s decision shutting down the Doe investigation shows the justices felt a strong kinship with the targets of the investigation. A potential jury member with the same conflicts would likely to be excused from a jury for cause.

To leave the recusal issue to the subjective judgment of the judge seems a mistake. In Justice Kennedy’s words, “Justice Benjamin conducted a probing search into his actual motives and inclinations; and he found none to be improper.” Allowing the judges to make their own decision about their own biases is likely to lead to decisions made by panels of judges with the least self-awareness and the strongest desire to decide a case, just the opposite of the kind of judge we would hope for.

In recent years there has been an explosion of spending on judicial races. Wisconsin has been among the leaders in this explosion. Several of the Caperton amici briefs singled out races in four states, including the 2008 Wisconsin Supreme Court race in which almost $6 million was spent by all sides.

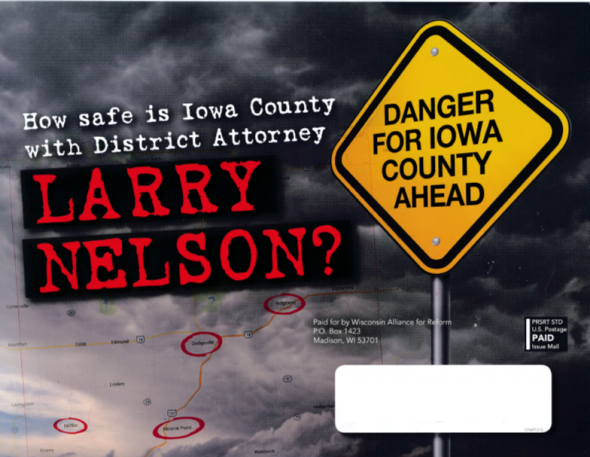

Typically this spending does little to elucidate underlying issues. More commonly it funds campaign ads that seek to bury the issue that is important to the sponsor. Instead these groups dig up cases that can be used to give the impression the target is soft on crime or made some other mistake. The myth of innocent “issue ads,” with a thoughtful discussion of the finer points of public policy, is quickly dispelled by viewing an actual issue ad.

Shown here is an example, the kind that often appears in judicial races. It is a flyer attacking Iowa County District Attorney Larry Nelson. It is considered an issue ad because the fine print says, “Call District Attorney Larry Nelson at 608-935-0393. Tell him to put the safety of Iowa County families first.” Because it doesn’t advocate Nelson’s defeat in a judicial election, it is immune to regulation under current law.

Recipients of this ad might conclude its sponsors were concerned about improving the administration of justice around Dodgeville and Mineral Point. There is no hint that the true motivation is to punish Nelson for his leadership in the John Doe probe of coordination between the Walker campaign and various outside groups.

Opponents of regulation of campaign spending like to claim they are defending the First Amendment—that they are protecting free speech. From their actions, however, it is hard to take this claim seriously. In a letter to Wisconsin Attorney General Brad Schimel, R. J. Johnson and Deborah Jordahl demand that Schimel punish Special Prosecutor Schmitz for his speech:

Any effort on his part to pursue a certiorari petition, or to take any other act apart from those assigned to him, would be contempt of court. If that would occur, we would expect you to act promptly in seeking sanctions accordingly, or to join any effort to seek sanctions for contempt.

Second, he made a direct reference to the persons and organizations that were the subjects of his improper John Doe investigation as “these special interest groups.” He then compared the subjects, including us, unfavorably with “violent criminals and terrorists,” saying, “My career in the military and as a federal prosecutor fighting violent criminals and terrorists did not fully prepare me for the tactics employed by these special interest groups.”

Third, he made a thinly-veiled and false suggestion that we corruptly influenced the judicial process in this case, writing, “The miscalculation I made in this investigation was underestimating the power and influence special interest groups have in Wisconsin politics.”

They then urge the Attorney General to use the legal process to silence the Special Prosecutor:

We also call upon you to pursue a motion for an order to show cause why Mr. Schmitz should not be held in contempt of the Wisconsin Supreme Court if he takes any further action inconsistent with that court’s December 2 and December 4 orders. Finally, we ask you to invoke and use whatever powers your office and your department have to investigate and remedy the conduct of the outgoing special prosecutor to date, both as set out here and as your own knowledge may suggest or your efforts may uncover.

The adoption of a firm recusal rule would have no impact on free speech. Individuals and organizations would still be free to run ads influencing elections. However, they would do so knowing they might be disappointed if they expected that candidate to vote for their interests. The judge who benefitted from their largesse would be expected to recuse him or herself in cases where the donor stood to directly gain.

This would have two beneficial effects in my view. First, it would reduce the incentive for the rapid increase in spending on judicial races. Second, it would help dispel the impression that American justice can be bought and sold.

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

This is an excellent article, well written, well reasoned, and right on target. Anyone concerned about the integrity of our judicial system will be grateful for your analysis.