Four Ways of Viewing Women

Haggerty Museum multi-exhibit show smartly spans centuries and attitudes toward women.

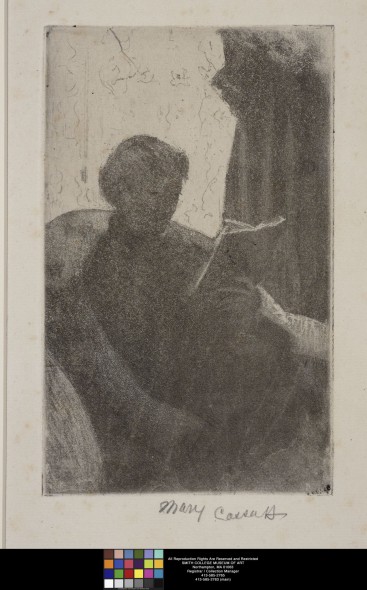

Mary Cassatt American (1844 – 1926). Lydia Reading, Turned Toward Right, 1881. Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton Massachusetts. Gift of Selma Erving, class of 1927

Early on in a multi-exhibit show about women currently at the Haggerty Museum of Art, I ran into a work by French satirist and painter Honore Daumier. Well known as a champion of the underdog and outspoken critic of the class system in 19th Century France, Daumier was certainly was not a Feminist! His scathing satirical drawing portrays a woman reading while her unattended little child is drowning next to her in a bucket of water.

This is among the images in four exhibits which explore the representation of women across time, cultures and media, now at the Haggerty.

In the very first room a small exhibit entitled “Page Turners” may seem too scholarly to some — lots of text panels and descriptions and mostly small, black-and-white images, not eye-popping stuff. But I encourage you to give it a try.

This is a survey of images of women reading which traces the social significance of this motif, with images and texts going back to the 16th Century, from the Haggerty’s permanent collection.

The early images from the 16th century suggest the model for educated women was reading for a religious or mediative purpose. Usually it’s the Good Book, the Bible being read, as in the many images of the Virgin Mary, particularly of the Annunciation. Reading is a symbol of domesticity and peacefulness. Reading attests to greater spirituality and devotion.

The 18th century saw an increase in women’s literacy and a corresponding rise in the number of female readers and writers. The manuscripts and images by then had changed to advocating reading as way for women to improve and educate themselves.

The novel was especially suited to the female reader and became the popular choice for women writers. Romanticism and Gothic romances were revolutionary and also the beginnings of feminism. Mary Wollstonecraft is generally regarded as the first English feminist author; In “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman” (1792), she advanced the philosophy that a “rational” education would produce women who were not only better wives and mothers but also the social equals of men.

Horrors, thought men like Daumier and his satire is here joined by other images from this period suggesting the negative effects of education for women.

Carrie Schneider American, b. 1979. Abigail reading Angela Davis (An Autobiography, 1974) from the series Reading Women (2012–2014). Courtesy of the artist and Monique Meloche Gallery

But by the late 19th century and early 20th century this particular backlash had subsided, to be succeeded by images portraying women reading as the way to find or express an inner life, the inner psyche. These include some very gentle images by James Abbot McNeil Whistler and Mary Cassatt and some later prints by well-known artists Lovis Corinth, John Sloan and Kathe Kolwitz.

The exhibit concludes with photos of an early Womens’ Readers Circle and a photo from 1909 of a group of women students at Marquette University — the first Jesuit Institution to admit women. What would Daumier think?

If this first exhibit shows us women reading, the next is about reading women. The exhibit, entitled “Reading Women 2012-2014,” features photographs of women reading books by women authors, by Brooklyn artist Carrie Schneider. These large, film-based color prints are the antithesis of the small, black-and-white images in the first exhibit and they have little text to explain them.

The subjects are women, friends of the artist, reading books by women authors. Schneider asked them to choose a book and read for several hours. She photographed them with a long lens to avoid interrupting them, using natural light and referencing the paintings of Vermeer. The quietness and calm that permeates these images is suggestive of the Flemish master. The women are absorbed in their revery, usually in comfy chairs with natural light streaming in a window. We are allowed to observe this very solitary process and become lulled by their contemplation. These might sound sentimental but I did not find them so.

Most of the readers are between 20 and 35, and the books they read are available for the gallery visitor to peruse. Many are famous texts by famous women. The women seem engaged and contemplative, female but not necessity “feminine.” We are now far removed from the sexualized male gaze of women; There’s a lovely intimate quality we seldom encounter in more conventional or dramatic images of women.

Accompanying this exhibit is a four-hour video installation which reinforces the photos’ floating feeling of getting “lost” in a good book. There is also an artists’ book of the photos in the exhibit.

Joan of Arc. Jules-Claude Ziegler, French, 1804 – 1856. Museum purchase

Collection of the Haggerty Museum of Art, Marquette University.

The third exhibit here is :”Joan of Arc Highlights from the Permanent Collection,” which celebrates the 50th Anniversary of Joan of Arc Chapel. Among the few Medieval structures in the western hemisphere, the chapel was moved first to Long Island in the 1920’s and eventually donated to Marquette by a wealthy patron in 1964. The chapel is still used daily for mass and docent-led tours are available.This little exhibit encompasses a range of very romantic, idealized sculptures, paintings and tapestries of the “Maid of Orleans,” the young heroine of the French and the Catholic Church, whose life and impact are still debated to this day.

The fourth exhibit is entitled “Bijinga: Picturing Women in Japanese Prints” and is also a survey of images of women, this time from the 17th century to the present as portrayed in classic Japanese woodblock prints. During the Edo Period (c. 1603-1868) in Japan, a new art form — “Ukiyo-e”– emerged, with its famous pictures of the floating world. These prints predate photography and are distinctive in that they were created for the merchant class, rather than the top tier of royalty and wealthy people.

The deceptively simple prints are exquisite in their technical and compositional aspects. Subtly blended, brilliant colors are juxtaposed to delicate, fine line drawings, a hallmark of the Japanese craftsman. The subject of this show are the beautiful women who lived in the pleasure quarters of Edo, as Tokyo was then called. The women were waitresses, actresses and courtesans — more active than the reading women we saw earlier.

The Haggerty also currently features a fifth mini-exhibit, which is not part of the women’s show but does in a way relate to it. It’s a teaching show featuring two small paintings by Jacob Lawrence, the African American artist. The display breaks down the processes and techniques of Lawrence, talking about materials and showing examples of his paint and color combinations.

Bijinga. Utagawa Hiroshige Japanese, 1797 – 1858. Snow Scene at Ueno park (on the banks of the Shinobazu Lake (Edo)), 1847 -1848. Collection of the Haggerty Museum of Art, Marquette University

It’s a lovely little exhibit and meant to help celebrate Black History Month, but after you see the techniques and materials Lawrence used and finally get to the paintings they hit you like a thunderbolt. These are very urban, depressing, and surprisingly brutal social documents done shortly before the artist checked himself into the Hillside Hospital in Queens for depression. He remained in treatment for 11 months.

Yet these paintings were actually illustrations commissioned for Seventeen Magazine, which adds to the surprise. The’re two versions of the painting, “Birth and the Fur Coat.” They were meant to illustrate the magazine’s story about a social worker (who wears the fur coat) visiting a woman whose baby lies dead on a bed. One version is less bracing than the other and was used by the publication, but it seems unfathomable today that either could have been used, or that such gritty, harsh subject matter would be found in the pages of a magazine for teen-age girls. Clearly the magazine’s editors felt these young women were capable of a seriousness unlikely to be found in such publications today. The exhibits suggest the advance of women hasn’t been a steady movement forward.

The Lawrence mini-exhibit closes at the end of February and the four women’s oriented exhibits run through May 22 at the Marquette University Haggerty Museum of Art on the MU campus.

Gallery

Art

-

Winning Artists Works on Display

May 30th, 2024 by Annie Raab

May 30th, 2024 by Annie Raab

-

5 Huge Rainbow Arcs Coming To Downtown

Apr 29th, 2024 by Jeramey Jannene

Apr 29th, 2024 by Jeramey Jannene

-

Exhibit Tells Story of Vietnam War Resistors in the Military

Mar 29th, 2024 by Bill Christofferson

Mar 29th, 2024 by Bill Christofferson

Can’t wait to see the Women’s show at the Haggerty! Thank you for the great review, Rose Balistreri, which makes me want to see it even more!