Arsenic Still Poisons Many Wells

Despite state efforts, problem persists in 51 of 72 counties, affects more than 22,000 homes.

State steps up regulation

In 2004, the DNR introduced tougher arsenic laws in Winnebago and Outagamie counties. With 20 percent of the private well samples there analyzed in 1992-93 exceeding the EPA’s new health standard of 10 ppb, this area was thought to pose the greatest exposure threat to the largest number of residents. The new regulation required all drilling and disinfection methods to minimize the exposure of sulfide rocks to oxygen.

For Luczaj, this was a step in the right direction, but he said it may not go far enough.

“The geology doesn’t stop at political boundaries,” Luczaj said. “The area definitely extends into the neighboring counties. It’s pretty likely that we’ll see increasing problems as aquifers get drawn down.”

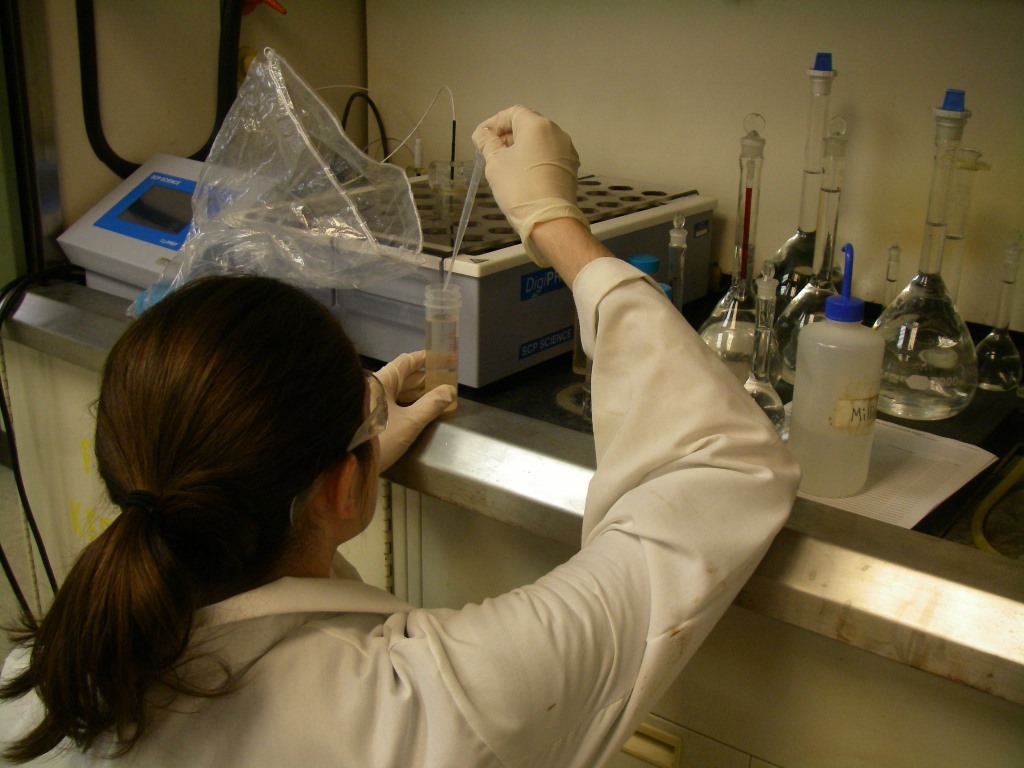

Former University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point student Jessica Peterson prepares water samples to test for metals and arsenic at the school’s Center for Watershed Science and Education. Some parts of Wisconsin have unsafe levels of arsenic in the drinking water. Photo by Debra Sisk of UW-Stevens Point.

A 2013 study of 3,868 private wells from across the state found 2.4 percent of them exceeded arsenic levels of 10 ppb. If that proportion was applied to all of the estimated 940,000 households on private wells in Wisconsin — a calculation endorsed by the study’s lead author — residents of 22,560 homes may be consuming unsafe levels of the chemical.

Testing, grants rarely used

The DNR has a well compensation grant program that makes residents whose well water exceeds 50 ppb of arsenic — five times the federal standard — eligible for up to $9,000 to drill a new well. The program can be used to address other types of contamination as well.

However, during the past five years, only 10 or fewer grants were awarded per year. Households whose water contains up to 49 ppb — almost 10 times the amount of arsenic shown to impact a child’s intellectual development — have to cover the cost of a new well on their own, or pay for other options that will make their water safe to drink.

Raising that awareness was part of Rohr’s goals when he began his water study in 2003. In 2014 — 11 years after Rohr’s study — the DNR revised its arsenic regulation yet again, recognizing the persistent nature of Wisconsin’s arsenic problem.

This time, the new state law required that arsenic, in addition to coliform bacteria and nitrate, be tested at the time of a property transfer, but only if the buyer requests a well inspection. The same three contaminants also have to be tested after the completion of certain well repair work, such as fixing a broken water pump.

Laughrin said the new law helps address one of his long-held concerns with people only testing their water for bacteria and nitrate: when those results are within safe ranges, they assume everything else is fine as well. And yet their water may be contaminated with arsenic or other substances for which the water has never been tested.

Given the potential for negative health effects from regular consumption of unsafe drinking water, Laughrin suggested another group of stakeholders who could play a large role in raising people’s awareness: family physicians.

“When my wife and I went to our doctor’s office four or five years ago, they did not even ask if we had a private or municipal well,” he said. “They’re starting to do it more often now. But there’s a lot to go on this yet.”

Bad wells replaced by city water

Some communities in Wisconsin have addressed their arsenic problem by offering citizens a switch from private to municipal water. The Stilson family in Oshkosh took advantage of this opportunity in 2000, following several years of having bottled water delivered to their home after the level of arsenic in their well rose to 999 ppb, or nearly 100 times the health standard.

“We said, ‘Let’s just get city water and get it over with,’ ” Lynn Stilson said. “Some people kept their well so they could use the water for their lawn, but ours was capped, we just got it all done at once. I think at this point everybody here has city water.”

In 2013, the city of Algoma water utility in Kewaunee County offered discounted arsenic testing to private well owners to gauge their interest in connecting additional homes to public water.

They found that 9 percent of the 330 homeowners who participated had levels above 10 ppb, with a maximum of 1,000 ppb. In 2014, the utility built water main extensions in neighborhoods with at least 70 percent of residents indicating an interest in switching to municipal water.

City water is required by law to be tested regularly for arsenic, which takes the burden of monitoring water quality off the homeowners’ shoulders. And public wells have another advantage over private wells: they tend to be drilled deeper.

“The private wells are generally shallower and more likely to draw water from near the water table,” Luczaj said. “In general, municipal wells are also constructed at higher quality than private wells.”

Wisconsin’s public water systems have only rarely exceeded the federal arsenic standard, although municipal well operators in some places, including the village of Suring in Oconto County, continue to struggle with arsenic problems that first emerged six years ago.

When drilling a new well is too expensive, a switch to city water not possible, or purchasing bottled water too big a hassle, another remediation option is to install an in-home water treatment system. The most cost-effective method is called a reverse osmosis system, which removes 95 percent of arsenic, as well as other contaminants.

Luczaj said vigilance is the key to avoiding arsenic, since human activity can increase the amount of the naturally occurring contaminant in well water. “A one-time test for arsenic is not at all sufficient,”he said.

Added Kevin Masarik, groundwater education specialist at the UW-Stevens Point: “A lot of people only test their water because they perceive a problem based on a color or odor issue. But they are largely ignorant of important tests to consider (for contaminants) that they may not be able to taste, see or smell.”

Gabrielle Menard and Elise Bayer, students in the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication, contributed to this story. This report was produced as part of journalism classes participating in The Confluence, a collaborative project involving the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism and UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. The nonprofit Center (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Article Continues - Pages: 1 2

Tainted Water

-

Fecal Microbes In 60% of Sampled Wells

Jun 12th, 2017 by Coburn Dukehart

Jun 12th, 2017 by Coburn Dukehart

-

State’s Failures On Lead Pipes

Jan 15th, 2017 by Cara Lombardo and Dee J. Hall

Jan 15th, 2017 by Cara Lombardo and Dee J. Hall

-

Lax Rules Expose Kids To Lead-Tainted Water

Dec 19th, 2016 by Cara Lombardo and Dee J. Hall

Dec 19th, 2016 by Cara Lombardo and Dee J. Hall