Present Music Has a Carnival

A daringly updated version of Schumann was among several crazy things at this concert.

Present Music’s artistic director, Kevin Stalheim, ceded the artistic reins to pianist Cory Smythe for Saturday evening’s program titled “Carnival.” Letting an artist of Smythe’s caliber develop an idea and run with it makes tremendous sense. Smythe is a elegant pianist and deserves a program of his own with which to create an experience for a sophisticated and devoted audience.

Robert Schumann’s Carnaval, Op. 9, would not spring to mind as a part of Present Music’s repertoire wheelhouse. Romantic-era piano music is the bailiwick of others in town. The solution for bringing this set of 22 movements up to date was to replace the 11 enigmatic notes from the movement Sphinxes—which is rarely played—with Smythe’s own improvisatory interjections (accompanied by minimal looping electronic tone patterns) and the additional insertion of music by self-taught Italian composer Salvatore Sciarrino.

The second power of the Sphinx is “to dare.” Here, too, Smythe was bold and successful. In Schumann’s score, Sphinxes appears between the eighth and ninth movements. Smythe separated the three bars of music, scattered them throughout the program, and improvised material over an electric accompaniment. Normally Schumann’s work is done without this eleven-note section, but pianist Sergei Rachmaninoff, for example, recorded his own improvisation of that spare thematic motif, so it has been done. Smythe’s improvisational offerings on the Sphinx were more complex but also much more musically vague, only hinting at Schumann’s music. The addition of Sciarrino’s Perduto una città d’acque, and Due Notturni: I and Due Notturni: II was also a daring programming choice but failed to leave any lasting impression. There is a temptation when listening to some modern music or viewing some modern art to think, “Hey, I could do that.” Well, in fact, no, you couldn’t. Sciarrino’s compositions and Smythe’s improvisations tended to create the sound one hears exiting the elevator on the practice room floor at the Juilliard School and hearing a miasma of pianists hammering out their aspirations—one phrase taking turns with another, each seeking supremacy but creating only madness. In the end you might not like it or understand it, but challenging yourself to be open to it matters a great deal.

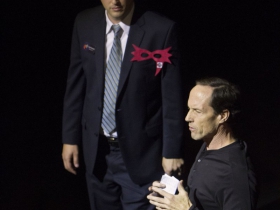

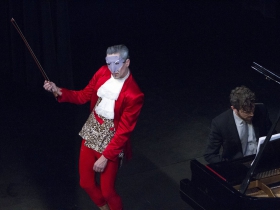

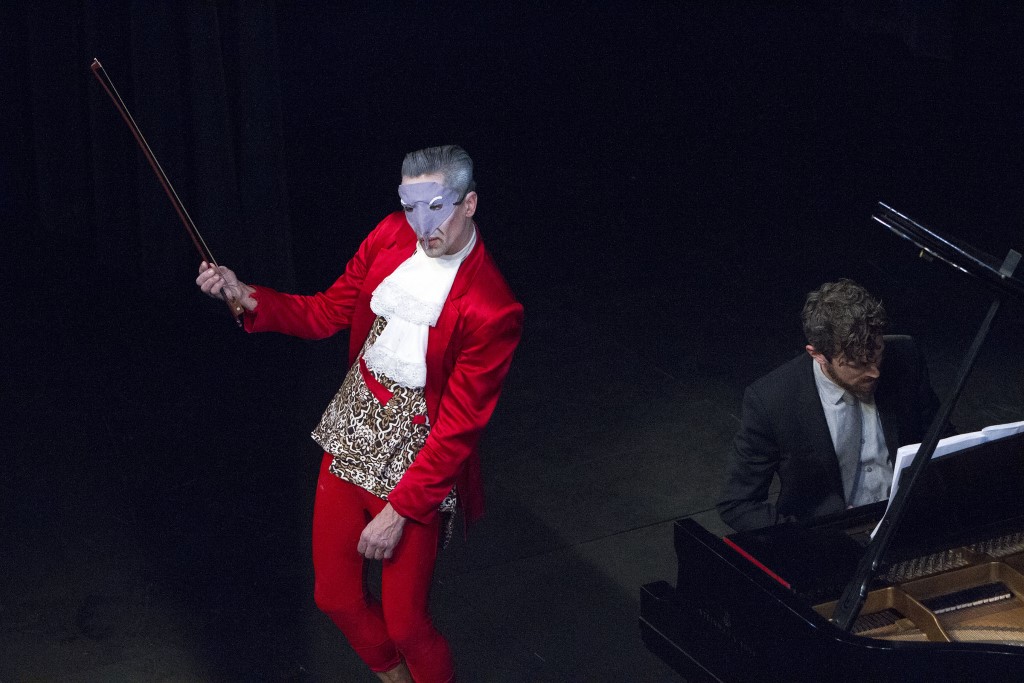

Another brave move was including Quasimondo Physical Theater’s commedia dell’arte actors. Schumann envisioned his work as having a carnival atmosphere, with stereotyped characters improvising along with the music. QPT’s bizarre pantomime devolved regularly into spasmodic silliness (lazzi), but that and awkward interpretive dance moves were distractions, not enhancements, to Smythe’s playing.

The third power of the Sphinx is “to will.” Smythe carried out the carnival atmosphere of the program with a vision for spectacle. Adding the commedia dell’arte and Sciarrino to his own piano virtuosity and improvisation in the Schumann was an adventurous, if somewhat distracting, artistic choice. There was also an impressive showing of people in the audience at Broadway Theatre Center’s Cabot Theatre wearing carnival masks, sequins, and feather boas. Before the concert, pianist Ruben Piirainen was delightful, roaming the audience with his toy piano, playing such things as Golliwog’s Cakewalk by Debussy and Petrushka by Stravinsky before taking the stage with his miniature grand piano and jingling some Beethoven. As another prelude to Smythe, violinist Ilana Setapen appeared as Niccolò Paganini and played the spots off selections from 24 Caprices for Solo Violin. This was a tangential choice to the Paganini movement in the Schumann, and Setapen’s magnificent playing added to the spectacle.

The fourth power of the Sphinx is “to keep silent.” Schumann’s music stands quite well on its own and needs no additions to improve it. Although Smythe did not keep the silence of the Sphinx, something weird and interesting did happen. Smythe’s formidable skill is a gift to the artistic richness of Milwaukee, and the creative outlet that Present Music provides gives music lovers a place to try on new ideas and think about bigger questions like, “What is art?”

Carnival Gallery

Review

-

The Fitz Offers Elegant Brunches

Jun 14th, 2025 by Cari Taylor-Carlson

Jun 14th, 2025 by Cari Taylor-Carlson

-

Ruta’s Offers Unique Twist on Indian Staples

Jun 1st, 2025 by Cari Taylor-Carlson

Jun 1st, 2025 by Cari Taylor-Carlson

-

Tre Rivali Offers Delicious Brunches

May 25th, 2025 by Cari Taylor-Carlson

May 25th, 2025 by Cari Taylor-Carlson

![Ruben Piirainen [r] Ruben Piirainen [r]](https://urbanmilwaukee.com/wp-content/gallery/historic-third-ward/thumbs/thumbs_mg_2717.jpg)