Exploding the Myths About Poverty

America didn’t “lose” the War on Poverty. Poverty declined. Can it be reduced further in cities like Milwaukee?

Fifty years after the start of the War on Poverty, two propositions have become widely accepted: (1) that it failed to reduce poverty and, therefore, (2) there is little society can do to reduce poverty. How do these propositions stand up to the evidence? For a city like Milwaukee, with a high rate of poverty, such questions are crucial.

Fifty years ago, there was great optimism that poverty could be eliminated or, failing that, it could be greatly reduced. There was no excuse, it was argued, for the richest nation on earth to have pockets of grinding inner-city and rural poverty.

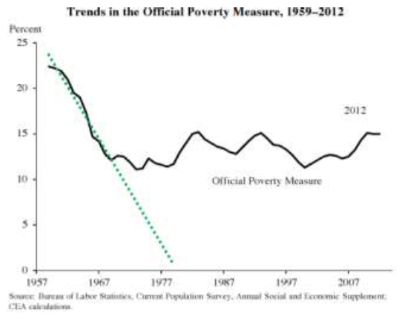

The figure to the right, taken from the 50th anniversary report from the Council of Economic Advisers, suggests that there was good reason for optimism. In the 1960s, the nation’s poverty had been on a sharply downward trajectory. In ten years the poverty rate was cut in half, mostly due to expansions in social security and a strong economy. If the trend had continued, poverty would have been largely eliminated by 1980.

Since then, however, the official poverty rate has oscillated between 10 and 15 percent, with no evident trend. Partly this reflects how it has been measured. The official poverty measure was developed at the dawn of the War on Poverty. It started with an estimate of the income needed for an adequate diet. That number was multiplied by a factor of three because surveys indicated families spent one-third of their income on food.

In the words of the Council of Economic Advisers, the official poverty measure “has not aged well.” For example, it ignores the effect of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP or food stamps), the two largest non-health related programs aimed at the poor. However, its use does serve the purposes of those, such as Wisconsin’s Paul Ryan and various editorialists, who wish to declare the War on Poverty a failure.

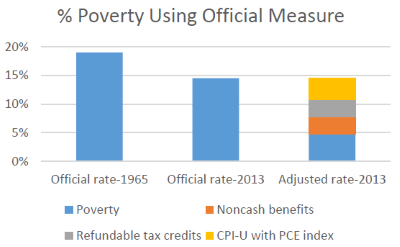

Last month Harvard’s Christopher Jencks published an article entitled The War on Poverty: Was It Lost? In the New York Review of Books. Jencks includes an estimate of how the official rate would look if it included changes to the laws since 1965 and uses a more realistic adjustment to the cost of living. The chart to the right summarizes Jencks’ calculations. Between 1964 and 2013, the official poverty rate shows the number of poor dropping from 19.0 percent to 14.5 percent. But Jencks argues that the 2013 rate should be further reduced to make it comparable to the 1964 rate, because of three factors: the value of noncash benefits, refundable income tax credits, and use of a more realistic cost-of-living index to compare prices in 1965 and 2013. Jencks’ recalculation shows the number in poverty dropping from 19 percent to less than 5 percent. He goes on to suggest the difference is due more to undercounting poverty in 1965 than over-counting it today.

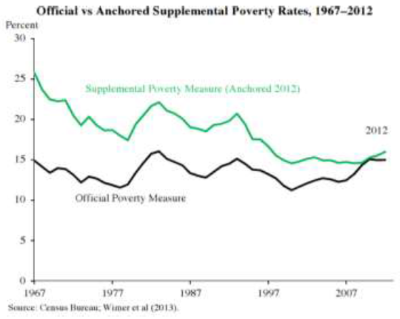

Recognizing the limitations of the official poverty rate, the Census Bureau created a Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM). It counts as income the value of several benefit programs, such the EITC and SNAP, but also subtracts tax liabilities and expenses for health care, child care, and work when computing a family’s resources, since these reduce funds available for food or housing.

Even the SPM has limitations. For instance it includes the financial benefits of having health insurance but ignores the health benefits.

Using the SPM does give a less dismal picture of the nation’s progress against poverty, as shown in the next plot. Using that measure, poverty was much higher in 1967 than estimated using the official rate, and has declined since from 25 percent to around 15 percent. It also appears that the various anti-poverty programs helped prevent a surge in poverty during the Great Recession.

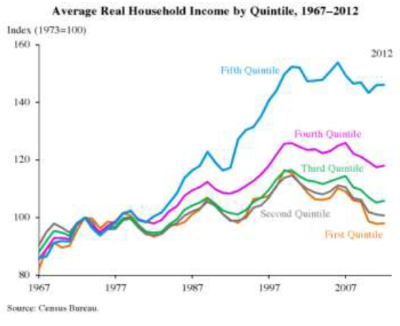

Recent global economic trends have likely worked against reducing American poverty. These include globalization itself, which has meant the movement of manufacturing jobs to countries with the lowest manufacturing labor costs, which has particularly impacted Wisconsin. Related to this has been the trend towards greater inequality, with an increasing share of income and wealth captured by a smaller and smaller share of the population.

Given these economic trends, perhaps the fact that poverty has not gotten worse should be viewed as an accomplishment. The evidence suggests programs like SNAP and the EITC have been key factors. Could other steps to taken to reduce the nation’s poverty rate?

To examine this question, David Riemer and the #Community Advocates Public Policy Institute# (where he is a senior fellow) looked at the issue. Riemer helped design the New Hope program to replace welfare with work, and has long been concerned about poverty in urban areas like Milwaukee. His group recently issued a plan that included five proposals:

- Create a transitional jobs program paying a minimum wage for unemployed and underemployed people;

- Increase the federal minimum wage to $10.10 an hour;

- Expand the earned income tax credit, providing a roughly $4,000 increase in the maximum credit for both childless taxpayers and taxpayers with children, and virtually eliminating the credit’s marriage penalty by allowing both members of a married couple to claim the credit based on their individual earnings;

- Expand funding for child care subsidies to make them available to individuals with incomes below 150 percent of the official poverty guidelines;

- Enacting a tax credit to raise Social Security and disability payment recipients’ income to 150 percent of the official poverty guidelines.

One argument often made against proposals to reduce poverty is that they may reduce the incentive for people to work. This was the major argument against extending unemployment benefits during the Great Recession—rather than take the first job offer that came along, people were living off the benefits while awaiting a job closer to the one they lost. It is notable, therefore, that the first four proposals would increase the incentives to work and, in the case of transitional jobs, encourage people to join the job market. The fifth targets a population that is expected to stay out of the job market.

Many proposals to alleviate poverty don’t attempt to measure their impact against the size of the problem. To address that problem, Community Advocates asked the Urban Institute to estimate the impact of the five proposals using its model used for simulating the effects of tax and transfer systems in the U.S. In its report, the Urban Institute described the projected poverty levels for 2010 with and without the five proposals.

The Urban Institute chose 2010 in part because it represented the height of the recession and also because it offered the use of the 2010 census results. The baseline used reflected tax and transfer policies in place in 2010 with two exceptions. It corrected the 2010 baseline to eliminate two temporary programs that were part of the stimulus package: the Making Work Pay tax credit and the short-term increase in SNAP benefits.

Based on its analysis, using the Census Bureau’s Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), the Urban Institute concludes the policy package as a whole would reduce SPM poverty from the base rate of 14.8 percent to somewhere between 6.3 percent to 7.4 percent, depending on how many of those eligible would take the transitional job offer. This means the number of people in poverty would drop by half or more.

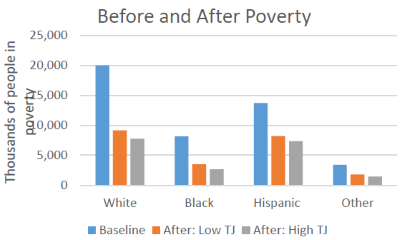

The chart to the right shows before and after estimates of the number of people in poverty. Contrary to the widespread perception that poverty is a minority problem, whites are projected to see the greatest poverty reduction. The reduction among Hispanics is projected to be smaller than in the other two groups because undocumented immigrants would not be eligible for transitional jobs.

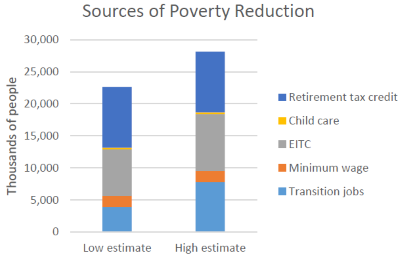

The next chart shows the impact of the five policies on the number of people in poverty. The difference between the “low impact” and “high impact” numbers is due mainly to differing assumptions about how many people would take transition jobs and the effect of the expanded EITC on jobs.

Many worthy proposals have been made to reduce poverty or to ameliorate its effects. There are so many, however, that they pose the danger of overwhelming voters and taxpayers. Where to start? By projecting the impact of a set of proposals on poverty reduction, the Community Advocates proposal and the Urban Institute evaluation offers a way out of this quandary.

The two widely-believed propositions posed at the beginning of this article turn out to be myths. When properly measured, poverty has gone down in the past 50 years. And despite the myths, poverty is not intractable. But that doesn’t mean proposals to further reduce poverty should be accepted on faith or good intentions. Proposals to reduce poverty can and should be analyzed and quantified.

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

You have to love the creativity of the left in trying to redefine the meaning of success for a clearly failed program. So are we to presume that the large segment of the population that is no longer in poverty does not need help from poverty assistance programs? Hello?! -that would be the logical inconsistency of the primary argument being made in this article.

If you call having people and families receiving government poverty assistance for generations, with no end in sight, a success, then the war on poverty is a success. So when does the war end? Or if the war is won, why are we forever spending more money on it? Is this what those “Stop Endless War” bumper stickers are about?

Bruce Thompson is not impartial on the issues he writes about, and this is just another issue where he shows his bias. His strawman argument that those opposing the status quo believe “there is little society can do to reduce poverty” is false. As we probably all can agree, receiving a good education is the best means to move out of generational poverty. The right has proposed school reforms, including school choice. But, the left is firmly entrenched in keeping failed public school systems operating as they are. When is the last time the left has tried to reform the Milwaukee Public School system other than by asking for more money?

If you truly believe that the right has proposed school choice simply to help poor people escape poverty, can we talk Bill? I have a business proposal for you that you just can’t miss out on.

PMD- You can hatefully speculate about motivations all day long. But school choice is at least an attempt to improve the education of children subject to the disaster called MPS. If school choice is such a bad alternative relative to MPS, no one would use vouchers. But that isn’t the case. Milwaukee families are choosing what they believe is in the best interest of their children- how democratic!

But please PMD, tell us why the left hasn’t come up with a reform plan for MPS?

Yes middle class kids already attending a private school are using vouchers. That’s really helping drag kids out of poverty.

BT, this goes back to the fundamental difference that ultimately affects many of our differing political viewpoints. My personal belief is that to truly be out of poverty, one must have the means to support themselves at a living wage. This article once again speaks to your belief that simply having government benefits to reach that equivalent living wage is enough to consider one out of poverty. Our society would see far greater improvement if we work towards helping people out of the place where they rely on assistance and can instead support themselves. That would be true success in the war on poverty.

But there are times when government assistance is necessary right AG? When my father-in-law was laid off from GM (his wife was a stay-at-home mom to their three kids at the time), my wife’s family received food stamps until he went back to work. That seems like an example of the necessity of government benefits at certain times.

For sure, PMD. I’m not saying we shouldn’t have the safety net and assistance programs, I’m just saying that you can’t consider someone out of poverty until they’re at the point when they don’t need the assistance anymore.