Hundreds of Wells Polluted and Unusable in Southeast Wisconsin

Study traces problem to coal ash disposal by We Energies plants in Milwaukee and Kenosha counties.

Water fountains are taped over at Yorkville Elementary School in Racine County due to high levels of the metal molybdenum. The environmental group Clean Wisconsin alleges that coal ash buried in a school construction site is partly to blame. Photo by Cole Monka / Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

By: Ron Seely, Rachael Lallensack, Cole Monka and Daniel McKay

Hundreds of private wells in southeastern Wisconsin are so polluted that their owners cannot drink the water because of high levels of molybdenum. Now, an environmental advocacy group reports a link between the contaminated wells and building and road construction sites where We Energies disposed of coal ash, which contains the metal.

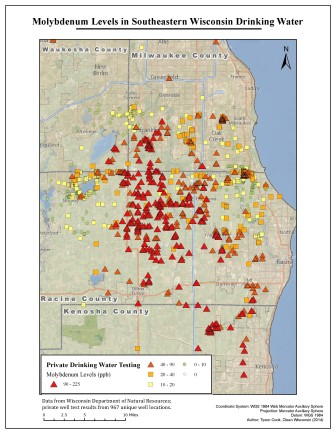

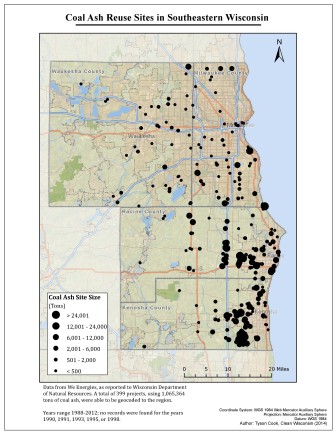

In a study released Tuesday, Clean Wisconsin connected high levels of molybdenum to the nearby presence of ash disposal sites and warned that similar contamination likely exists in other regions because Wisconsin has the nation’s highest rate of reuse of coal ash.

The waste left after coal is burned can contain concentrated levels of contaminants such as metals — arsenic, chromium, lead, mercury and molybdenum.

Of special concern, Clean Wisconsin said, were sites of so-called “beneficial reuse” where the ash had been used as fill for roads and bridges, or on construction sites, even for building a school. The practice is encouraged by the federal Environmental Protection Agency and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

Tyson Cook, director of science and research for Clean Wisconsin, said the group’s study is the first to link those reuse sites to contaminated wells. “There is a correlation between how close a well is to a coal ash reuse site and how high the levels of molybdenum are in that well,” Cook said.

He added that the issue is of statewide concern because an estimated 85 percent of coal ash is reused rather than being disposed of in lined landfills, where it cannot leach into groundwater.

The group reported that nearly half of 1,000 wells tested in Waukesha, Racine, Milwaukee and Kenosha counties showed high levels of molybdenum.

The metal occurs naturally at low levels. It has been shown at high levels to cause developmental problems in animals and gout-like diseases in humans, leading to joint pains, enlargement of the liver and other problems.

The potential connection between coal ash and polluted wells in the region has been investigated previously. The DNR, in a study released last year, focused on three coal ash landfills in the Caledonia area, where many of the contaminated wells are clustered. The DNR’s study did not find evidence that definitively pointed to the landfills as the culprit.

But, according to the Clean Wisconsin report, the agency did not examine coal ash disposed of in reuse projects. The environmental group analyzed DNR records from 1988 through 2012 that showed 1.6 million tons of We Energies coal ash being reused in over 575 projects throughout the region. Five years of data were missing from the DNR’s tallies, according to Clean Wisconsin.

We Energies operates coal-burning power plants in Kenosha and Milwaukee counties.

Ann Coakley, director of DNR’s Bureau of Waste and Materials Management, said that the Clean Wisconsin report did not take into account the differing uses of coal ash in construction. Ninety percent of it, she said, is part of concrete, asphalt or wall board, and will not leach contaminants. But some of the material is used as fill, where it is less contained.

Coakley added that studies by the agency have shown no conclusive connection between sites where coal ash has been used for construction projects and wells with higher levels of molybdenum. She said that with the data used by Clean Wisconsin — wells in different geological settings and at different depths spread over four counties — the link between the ash and contaminated wells remains inconclusive.

“The correlation is not possible to make,” Coakley said. She added that the agency agrees further study is necessary.

Brian Manthey, a spokesman for We Energies, said that the company had not reviewed the report. But he said the company disposes of coal ash by following the regulations set by the DNR and the EPA.

“We believe the current DNR rules are the appropriate regulations for protection of the environment,” Manthey said. “Our disposal is done within the rules set by the DNR. And the EPA encourages beneficial use.”

Manthey said there are also other potential sources of molybdenum and added that it can occur naturally in rock.

But those natural levels are much lower than the levels found in the wells examined by Clean Wisconsin. The report said a survey of 2,700 wells in northern Wisconsin by the Department of Health Services found that 98 percent of samples had concentrations below 20 parts per billion.

The 1,000 wells examined in the Clean Wisconsin study, however, had an average of nearly 50 parts per billion of molybdenum, higher than the enforcement standard of 40 ppb set for drinking water by the DNR. That is the limit beyond which the agency can require action to correct the problem.

One in five of the wells exceeded the health standard of 90 ppb set by the Department of Health Services. That is the point where DHS recommends “that you not use your water for drinking or in foods where water is a main ingredient and that you find a different source of safe water to drink.”

The state health standard is more than double the EPA advisory level and, according to Clean Wisconsin, allows more molybdenum in drinking than the federal agency recommends children be exposed to for even a single day, 80 ppb.

Molybdenum levels were measured at up to 138 ppb, or over 70 percent higher than the one-day exposure level deemed safe for children by the EPA.

Now blue tape cordons off the water fountains and students drink only bottled water.

Katie Nekola, a lawyer for Clean Wisconsin who worked on the project, said the group is asking the state to conduct more testing of groundwater in areas where coal ash has been dumped or reused, establish complete reporting requirements for reuse of coal ash, require more testing of coal ash and stop spreading coal ash until better safeguards are in place.

Ron Seely is a reporter for the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism. Rachael Lallensack, Cole Monka and Daniel McKay are enrolled in one of eight journalism classes participating in The Confluence, a collaborative project involving the Center and UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. The nonprofit Center (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the journalism school. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

-

Wisconsin Lacks Clear System for Tracking Police Caught Lying

May 9th, 2024 by Jacob Resneck

May 9th, 2024 by Jacob Resneck

-

Voters With Disabilities Demand Electronic Voting Option

Apr 18th, 2024 by Alexander Shur

Apr 18th, 2024 by Alexander Shur

-

Few SNAP Recipients Reimbursed for Spoiled Food

Apr 9th, 2024 by Addie Costello

Apr 9th, 2024 by Addie Costello

When viewing the map of higher well monitoring levels for molybdenum, there does not appear to be a visual correlation to coal ash sites. High levels appear all over the map. As suggested, more study is needed and comparisons between proximity to known coal ash sites, ash in concrete projects, and sites known to be distant and not affected by coal ash.

During the process of urbanization, humans filled every low spot including wetlands along lakes, rivers, streams, etc. with garbage, incinerator ash, unlicensed fills and town dumps, farmers dumping on their own properties, and industry dumping solid and liquid waste wherever they could until the late 1970s, and some still do today if they can get away with it.

Our ability to test for water contaminants has greatly improved in the last few decades. We are testing levels today that were not possible more than 20 years ago. We also cut the budgets of departments like WDNR and expect them to do the impossible task of having this type of information at the ready, at a time when we continue to cripple them and protect public health.

An open pit mine that could open in the northern regions of WI that wrote the laws for environmental regulation and water quality – will leach all kinds of metals into surface and groundwater.

It’s a theory which certainly should be explored further, but saying there’s a definite “link” isn’t completely supported by the data to date. Moreover, the DNR is absolutely right in noting the difference between coal ash used in asphalt and concrete and coal ash placed in other circumstances.

That said, sorting through the data is absolutely something the WDNR should be doing. I don’t know if the WDNR has submitted their budget request yet, but something to deal with this issue should be in it.