Why the Mary Nohl Home Must Be Moved

At a fascinating forum, Ruth Kohler blasted Fox Point, explaining why the home and yard of artist Nohl will be moved to Sheboygan.

Ruth deYoung Kohler had a message for those who want to keep the Mary Nohl home in its original Fox Point location, rather than move it to Sheboygan County, as her foundation has proposed. “Come up with a miracle,” she told an audience of 200 at the Milwaukee Art Museum Thursday night, “or believe that we did our best.”

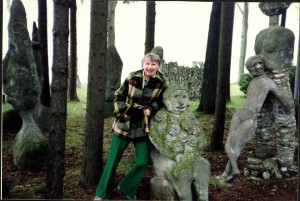

As I wrote in April in Urban Milwaukee, the artist’s home and yard, with its many works of art, would be preserved by moving it to Sheboygan County because of a failure to find “a mutually agreeable arrangement with the property’s neighbors along Beach Drive in Fox Point to allow limited public access to the property,” according to a press release by Creation and Preservation Partners, (CAPP), a John Michael Kohler Art Center [JMKAC]-affiliated organization.

The format was a panel discussion featuring a moderator and five speakers, of whom Kohler, the director of JMKAC since 1972, was the last. It had elements of an art history lecture; a tutorial on “Heritage Preservation;” an inquest; a memorial; a tribute and a trenchant commentary on the selfishness and narrow-mindedness of an isolated and privileged suburban elite.

Kohler admitted that her 27 years of working with Mary Nohl and later the Village of Fox Point to make her “work and architecture accessible to people and serve as inspiration to young artists,” had taken its emotional toll after a public meeting in Fox Point in October, 2013. [See “Plenty of Horne: Mary Nohl vs. NIMBY”].

The meeting included a presentation of its plans to preserve the Mary Nohl Lakeside Environment and its willingness to make the site available only by appointment, by advance reservation, at limited hours, and with shuttle service (no parking).

“But the neighbors voted down all conditions,” she told the forum Thursday, calling the public reaction to the plans “profoundly depressing. That night I felt our goals might be unattainable for perhaps a generation.”

The geographic distinction is culturally and politically significant. Fox Point originated as a community with two cultures. Generally speaking, the areas east of Lake Drive were lake and country homes and estates of the wealthy in the late 19th century, and are zoned 1-acre or larger. Here are some of the most valuable residences in the state — and some of the highest incomes. Beach Drive, with its rare lake-level frontage and 75 or so choice lots, is more valuable still, and proportionately more isolated, socially and geographically.

The much larger western portion of the 2.68 square mile village holds the majority of its 6,000+ residents on much smaller lots than the easterners — sometimes even in multi-family buildings — so as to better provide a tax base for the village schools. (You don’t see nearly as many University School buses on that side of town.) Much of this area was farmland until after World War II. Many of the residences are indistinguishable from working class urban homes of the era. The per capita income, while still robust, is much less than in the eastern district.

But the opinion of the west-of-Lake Drive does not matter in the politics of Fox Point, Kohler learned. In fact, Eric Fonstad, who lives at 7405 N. Beach Drive, next to the Nohl home, was so opposed to the project that he won a seat on the village board on this single issue in 2009.

Kohler said she started working with Nohl in 1987 to preserve the environment in situ. “She got more and more excited,” Kohler said, and in 1996 bequeathed the art, and then the home, with some restrictions. “In 2001 she removed the restrictions,” shortly before her death in 2002.

Kohler and her representatives met with the Village Manager and Village Attorney. The first step would be approval of a Cultural Overlay Zoning District.

She talked to UWM to partner with her group, and a doctoral student documented the grounds and artifacts.

“But the neighbors complained,” she said, and frustrated her attempts while the attorney fees piled up. A meeting with neighbors in 2004 was not successful, and in 2005 the Fox Point Police issued weekly citations for code violations. Neighbors monitored all visitors, including contractors, she said.

“At the same time we were nominated to the National Register of Historic Places.” A neighbor [Fonstad] sought revocation (unsuccessfully).

The Nohl Environment was named as one of the 10 most endangered sites in the state around then, and at a 2006 meeting with neighbors, Kohler said 100 residents showed up wearing “No Museum” signs.

Meanwhile, the Fox Point Village Board refused to meet with the Kohler representatives. Neighbors would use video to monitor the comings and goings at the Nohl home, she said. (Attorneys were able to stop that harassment, she said.)

As a contingency, in 2012 a feasibility study was made to determine if the site could be relocated after a flood filled the basement to the rafters in 2010, the second such incident since Nohl’s death.

In 2013 surveys were sent to neighbors living east of Lake Drive asking if they approved the zoning change that would keep the environment in situ. They wanted it gone.

Kohler said she was struck that the neighbors who supported retaining the environment did not want their opinions attributed to them out of concern about what their neighbors might think. “This is a very significant problem,” Kohler said, adding, “Fox Point is a gated community without a gate.”

As a result, Kohler said, she is now engaged in the “complex process” of moving the property to Sheboygan County. “Many are opposed to this process, and we don’t like it either. … We will try our damnedest to find a site near the water and some place that Mary would enjoy. We are proceeding in a manner that is most responsible at this point,” she said in conclusion, to a standing ovation.

More on the Forum

The forum was moderated by Polly Morris, the chair of the City of Milwaukee Public Art Subcommittee and administrator of the Greater Milwaukee Foundation Mary Nohl Fellowships since 2003. She is also the executive director of the Lynden Sculpture Garden in River Hills.

Morris called the Nohl site a “rare example of an art environment created by a woman.” She said she arranged the forum to “reset the discussion” and to look at the broader issues of environment preservation. These issues, she said, “are particularly difficult in small villages like River Hills and Fox Point,” where “best intentions do not always produce the best results.”

Lisa Stone of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, which counts Nohl among its alumni, gave an overview of preservation of similar environments around the country. Some of these benefitted from the support of JMKAC, which has preserved more sites than any entity in the world. “Without Kohler, support for these environments would have been long gone,” she said. It is crucial that groups like Kohler work expeditiously. Often a life change, or real estate change “signals the end of the road for the artist’s work.” She offered abundant examples of environments destroyed by heirs who considered the work junk. Some rescued artifacts are in museums today while their mates are in landfills.

Matt Jarosz of UWM and the City of Milwaukee Historic Preservation Commission gave an overview of successful and unsuccessful Milwaukee preservation efforts. Jarosz suggested a better term — commonly used abroad — is Heritage Preservation, since this puts things in a proper context. He says the ongoing work at the Soldier’s Home in Milwaukee will be of national interest: “the rest of the country will be looking at it for the next couple of years.”

John Gurda, a Milwaukee historian, gave a speech that exhibited the clarity and focus of a newspaper column. “Historic structures are definitive markers of place,” he said. “No landmark exists in a vacuum.” We have learned in nature that “to save an endangered species it is essential to preserve its habitat.”

“Stripped of context it is like a rose without a garden. This is particularly true when it is a garden as perfectly tended as Mary Nohl’s.”

Attendees included Julilly Kohler and her sister Marie Kohler, a recent appointee to the Wisconsin Humanities Council. The two are second-cousins to Ruth Kohler. Others included Rose Balistreri, Milwaukee Public Arts Subcommittee member and wife of Urban Milwaukee editor Bruce Murphy, Marsha Sehler, Lynn Lucius, Richard Taylor, Lynden artist in residence Dan Torop and Nicholas Frank. A call from the audience asked for Trustee Fonstad, but he was not there.

For More Information: Interested parties are urged to follow developments in the Nohl Environment by using the hashtag #Nohlforum on Twitter. The Facebook Page Save Mary Nohl’s Art Environment has 2,669 members. Questions may be directed to marynohl@jmkac.org. Here is a list of the Trustees of the Village of Fox Point.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

Art

-

Winning Artists Works on Display

May 30th, 2024 by Annie Raab

May 30th, 2024 by Annie Raab

-

5 Huge Rainbow Arcs Coming To Downtown

Apr 29th, 2024 by Jeramey Jannene

Apr 29th, 2024 by Jeramey Jannene

-

Exhibit Tells Story of Vietnam War Resistors in the Military

Mar 29th, 2024 by Bill Christofferson

Mar 29th, 2024 by Bill Christofferson

I found this presentation extremely informative and moving. It raised a lot of questions about how different people perceive and value “Art”.

Excellent panel. Polly Morris did a wonderful service to the community for clarifying the situation.

It was also really moving to see the audience so supportive of Ruth Kohler.

Also as a point of clarification,I am on the Milwaukee Arts Board but not on the Public Art Subcommittee.

For a good read, check out New Yorker Magazine’s feature article about the Twin Towers memorial..The Nohl issue is also an emotional issue, on both sides of the fence. Recently I had to move into a West Bend neighborhood where lock-step Neo Nazi thinking reigns. NIMBY takes on new meaning up here. The day I moved in, I was told by a resident that the Homeowner’s Association has ways of keeping “undesirables out.” When I asked just what was meant by that, an iron curtain descended. End of discussion.

I was unable to attend the Milwaukee Art Museum presentation, but a few years ago I visited Sterling North’s home (the author of the acclaimed Rascal, which I read as a teen and marvelled at his writing, not realizing then that North had written the memoir when he was in his 50s). I thought about whether Sterling North’s home would have as much authenticity if it were moved to another location, and even though the house was small and the historical elements in it not particularly numerous, my decision became a resounding NO! How I imagined North’s home in the book and the reality of his real home and the neighborhood in which he lived were vastly different, and it was discovering that difference that was so appealing to me. Mary Nohl’s home will not be the same in another location, no matter how many books are written about her and her artwork. Years from now one would want to visit the place where the artworks were actually created!