How Schools Use Technology in a Crisis

More Wisconsin districts use text messages but vast majority of MPS parents aren't part of system.

Police stand guard outside a Madison school, which went into lockdown May 2 along with schools in Verona, during a manhunt for a fugitive from Chicago. School districts are increasingly looking to new technology to contact parents in such emergencies — and in the fall, Verona will begin automatically signing parents up for text alerts and other emergency communications. Amber Arnold/Wisconsin State Journal

When a fugitive wanted by the FBI was spotted in the Madison area May 2, the Verona Area School District went into lockdown for more than two hours.

But many parents were unaware of the lockdown and of a manhunt launched by authorities. Text and email alerts were sent, but most parents of the district’s 5,000 students were not signed up to receive them.

“Timing is everything,” Gorrell said. “You don’t have those kind of emergency situations come up very often and when you do you’d like to be able to reach people.”

School officials use multiple approaches to notify parents, including emails and voice calls. Texting is the quickest method for some parents, but this option is not in widespread use.

Of the 10 largest school districts in Wisconsin, none automatically enrolls parents in text messages — as Verona, a smaller district, plans to do. But four of them allow parents to sign up for them by entering their cell phone number online.

Ken Trump, president of National School Safety and Security Services, says schools need to be able to communicate rapidly with parents in emergencies. Photo courtesy Ken Trump.

Even when parents can sign up for text alerts, many do not. In Milwaukee, the largest district in the state with more than 78,000 students, the text message system has only 4,300 subscribers.

With parents increasingly plugged in with smartphones and laptops, schools are under pressure to use new technology to stay in touch with parents.

When something bad happens at school, news travels fast. Cell phone pictures, texts and tweets emanate from the site and find their way to parents.

“With students and parents texting, information and misinformation gets out very rapidly,” said Ken Trump, president of National School Safety and Security Services, a Cleveland-based consulting firm. “Rumors that used to take hours and days to get out take seconds and minutes.”

By being the first to reach parents, Trump said, schools can mitigate panic and help avoid overloaded phone lines and packed parking lots.

“We’re in an information-now generation,” Trump said. “Schools will always be behind the curve on whatever information is out in the school community but they need to cut that gap.”

To this end, some Wisconsin schools are seeking to improve their ability to communicate with parents.

For instance, the Racine Unified School District recently updated its emergency communication system, adding the ability to send district-wide text messages.

“Parents expect to be notified ASAP, so we had to update our system so the message could go out more quickly,” said district spokeswoman Stacy Tapp.

Getting the word out

Besides texts, many school districts also use recorded voice calls, emails, website postings and social media to get out messages. Experts say the key is redundancy — the more channels, the more likely someone will get the message.

“If you want to get an emergency message out, you better use all available means,” said Ellen Miller, a former television journalist who now works as a consultant with National School Safety and Security Services.

“Parents hate hearing something from the media that their own school failed to tell them about,” Miller said.

In the Eau Claire Area School District, administrative assistant Patti Iverson said the district relies on the media, emails and phone calls to communicate with parents. She has not heard any complaints.

As for texting, she said, “We have looked into it and at this time, it was not in our opinion cost-effective to do that.”

One of the most popular companies that provides schools with emergency communication platforms is SchoolMessenger. More than 200 of the 445 school districts in Wisconsin use SchoolMessenger, according to the company.

SchoolMessenger systems cost $1 to $4 per student per year, and they all provide the capability for texting, according to Nate Brogan, vice president of marketing for SchoolMessenger.

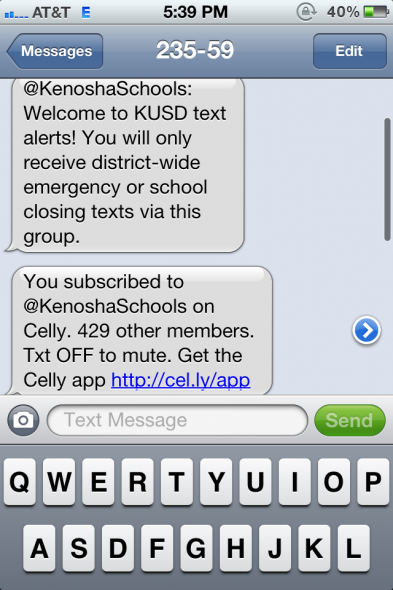

Kenosha Unified School District uses a free service called Celly to send texts to parents who sign up for it. The district has about 430 subscribers.

The Janesville School District has the capacity to send texts through its AlertNow system, but spokesman Brett Berg said it is not operable. In order to use it, he said the district would need to find a way to separate cell phone numbers from landlines in the system.

This year, the Kenosha Unified School District launched a text message system through a free service, Celly, and so far has 430 people signed up, according to district spokeswoman Tanya Ruder. The district has about 23,000 students.

The Madison School District requires parents to provide at least one emergency phone number for its recorded voice message notification system. Parents can also request emails and texts. The system has about 4,500 numbers for texts, and 20,000 for voice calls, spokeswoman Marcia Standiford said.

The district recently surveyed parents about the system. One of the questions was whether parents would prefer to be automatically enrolled in texts. Results are now being tabulated.

The trouble with waiting

The Green Bay Area Public School District uses SchoolMessenger, but has not used the program’s texting feature because of the potential cost to parents under their cell phone plans, district spokeswoman Amanda Brooker said.

Brooker said the district hopes to start providing text messages next year if it can find a way to allow parents to choose to sign up for them, rather than automatically enrolling them.

“Sixty percent of the students in our district have free and reduced lunch, so we have to be cognizant of that cost,” Brooker said. “I think parents were just so happy that we started using SchoolMessenger this year.”

Before this year, the district could not do voice calls and rarely used emails. Its standard for communication was to send students home with a letter, translated into different languages, sealed in envelopes, said Barbara Dorff, the district’s executive director of pupil services.

Even if the district had the ability to text, Dorff said, it might wait until an emergency situation is resolved to notify parents. This could prevent something she’s seen before: parents flocking to the school and making the situation worse.

Her message to parents: “We will take care of your child before we take care of you, and you should take comfort in that.”

But Miller said schools may no longer have the luxury of waiting to tell parents about an ongoing situation.

“The problem with doing that is a neighbor across the street is going to see a police car outside the school,” she said. “And if they scoop you on Twitter, you’ve lost the trust of the community.”

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication.

All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

-

Wisconsin Lacks Clear System for Tracking Police Caught Lying

May 9th, 2024 by Jacob Resneck

May 9th, 2024 by Jacob Resneck

-

Voters With Disabilities Demand Electronic Voting Option

Apr 18th, 2024 by Alexander Shur

Apr 18th, 2024 by Alexander Shur

-

Few SNAP Recipients Reimbursed for Spoiled Food

Apr 9th, 2024 by Addie Costello

Apr 9th, 2024 by Addie Costello