New State Law Increases Abortion Delays and Risk

Law passed last year restricts the use of drugs to end pregnancies, forcing more women to have surgery.

Samantha, who wanted to have a medication abortion in Milwaukee, changed her plans when she learned it could be difficult to obtain follow-up care. The state’s new abortion law took effect in April. Photo taken Jan. 18 at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee campus by John O’Hara.

Abortion pill restrictions part of nationwide push

Medication abortions have become more prevalent nationally in the past few years, and laws targeting them are sweeping state legislatures across the country. Read more here.

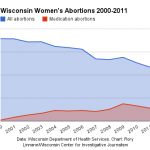

Chart:

Click the chart below to track abortions by Wisconsin women over the past decade.

The two pregnancy tests she took early last year had come up negative, but this time a faint plus sign surfaced in the plastic window. Samantha, 21, knew immediately what she wanted to do.

Within five minutes, she said, she called Affiliated Medical Services, a clinic in Milwaukee that provides abortion services.

“I was sort of hysterical when I called them,” said Samantha, who spoke to the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism on condition that her last name not be used to protect her privacy.

One week later, in a 30-minute session with a counselor at Affiliated Medical Services, Samantha and her partner listened to their options. She determined she would prefer a medication abortion to a surgical abortion. This would allow her to terminate the pregnancy earlier by taking one pill at the clinic, and a second pill at home to complete the abortion.

Samantha was carrying a 21-credit load at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and working 40 hours a week at a coffee shop. Overwhelmed, she hoped to obtain the abortion as quickly as possible before winter break ended.

But then the counselor raised a caveat.

“After she finished explaining the procedure, she hinted to us that it might be a difficult time to procure a medication abortion,” Samantha said.

Samantha later learned that state lawmakers were planning to change the rules for medication abortions, which could make it more difficult to obtain follow-up care.

“That was really scary,” said Samantha, who decided to wait several weeks to have a surgical abortion as she juggled work and school. She was fatigued and depressed.

“I was feeling stupid and bad about myself for it happening, and just the physical state of being pregnant,” said Samantha, who became pregnant because of a medical condition that rendered her birth control pills ineffective. “It was just terrible.”

The state’s new abortion law, Act 217, went into effect last April. It prompted the state’s two leading abortion providers, Affiliated Medical Services and Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin, to stop providing medication abortions that month.

Affiliated Medical Services resumed offering medication abortions in May, after a legal review. Planned Parenthood, which has filed a federal lawsuit against the law, is still not offering this option.

Billed as a way to make abortion safer for women, the law had the consequence of limiting access to medication-induced abortions, leading more women to have more invasive surgical abortions and putting some women at greater risk by increasing the wait-time for appointments.

Dr. Doug Laube, a University of Wisconsin-Madison professor and former president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, has condemned the new law.

“I believe that this law is legislated medicine generated by political ideology and it is a dangerous barrier to women seeking safe and legal nonsurgical abortion,” Laube said in a conference call with reporters, organized by Planned Parenthood in December. “This is an intrusion into the doctor-patient relationship and sound evidence-based medical practice.”

Safety concerns

Dr. Fredrik Broekhuizen, medical director for Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin, said surgical abortions require more time with physicians. This causes scheduling delays and increases the risk of complications.

Planned Parenthood and Affiliated Medical Services have reported delays ranging from a few days to more than two weeks. This sometimes means that medication abortions can no longer be done.

“While legal abortion is one of the safest procedures in the contemporary practice of medicine, a delay in performing a termination of the pregnancy may increase the risks to the patient’s health and life in some circumstances,” Broekhuizen wrote in a court filing.

According to Kelly Cleland, a researcher with the Office of Population Research at Princeton University, the earliest abortion is the safest abortion.

“Every week that goes by, it introduces more risk,” Cleland said. “So any argument that they’re trying to make it safer is a completely disingenuous argument.”

A new study published in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology found that less than 1 percent of the more than 200,000 medication abortions Planned Parenthood provided nationwide in 2009 and 2010 resulted in significant adverse events or outcomes. The most common of these was continued pregnancy.

A surgical abortion brings risks associated with any surgery, according to the National Institutes of Health, including internal damage, infection and excessive bleeding. Cleland said such events are rare, but there have not been recent studies in the United States that directly assess the risk of complications from surgical abortions.

Nicole Safar of Planned Parenthood Advocates of Wisconsin said the number of surgical abortions has risen at the group’s clinics following its decision to suspend medication abortions. Photo courtesy of Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin.

Nicole Safar, public policy director for Planned Parenthood Advocates of Wisconsin, stressed that both methods are “exceedingly safe,” but said some women have medical conditions that make the surgical abortion too difficult. Others prefer medication abortions for the privacy they offer.

“More than the physical piece, for many women medication abortion is the right choice for her entire self — emotionally, psychologically,” Safar said. “Many women would prefer to go through the process at home, with their family. That’s a huge piece of it you can’t really quantify.”

Since the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved mifepristone and misoprostol for abortions in 2000, Wisconsin women have increasingly relied on this option. In 2001, the state health department reported that about 5 percent of the more than 10,000 Wisconsin women who had abortions in the state chose the medication option.

In 2011, the state reported, 24 percent of the roughly 7,000 Wisconsin women who had abortions in the state chose the medication option. According to Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin, nearly half of the women eligible for medication abortions at the group’s clinics that year chose this option.

Women can only receive medication abortions in the first nine weeks of pregnancy, while surgical abortions are available up to 19 weeks of pregnancy at Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin.

Since April, however, the number of medication abortions performed at Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin clinics has dropped to zero. Though Safar said the number of surgical abortions for 2012 will not be available until March, she said doctors have noted an increase.

“The overall number (of abortions) is continuing to drop, but since we don’t offer another option, women who probably would have chosen medical abortions have had surgical abortions,” Safar said. “Women are opting to have surgical abortions, or they’re going somewhere else.”

Safar said doctors inform their patients of other places they can have a medication abortion, including clinics in Illinois, Minnesota and Iowa.

“Women shouldn’t have to drive anywhere,” Safar said. “Women deserve to have all safe and legal options available to them.”

Doctors at Affiliated Medical Services also provided more surgical abortions due to their roughly three-week suspension of medication abortions, according to Wendie Ashlock, the clinic’s director. In 2012, Ashlock said, they provided 1,925 surgical abortions, 68 more than the previous year. They also provided 523 medication abortions, 73 fewer than the previous year.

Telemedicine concern spurred law

In December, Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin filed a lawsuit in federal court seeking to get Act 217 either clarified or struck down. The group said it had to completely suspend nonsurgical abortions at its clinics due to the law’s “unconstitutionally vague” requirements for medication abortions and criminal penalties for doctors who don’t meet them.

Proponents of the change say it is needed to stop doctors from prescribing abortion medication over a webcam. That’s what has happened in Planned Parenthood clinics in Iowa, where a technician performs an ultrasound and a physician visits by webcam to review the woman’s records and prescribe the medication. The patient takes the first pill at the clinic, and the second later at home.

Officials at Planned Parenthood say they had no plans to use teleconferences for medication abortions in Wisconsin.

But Susan Armacost, legislative director of Right to Life Wisconsin, said she and other pro-life advocates feared this practice would spread to Wisconsin, putting women at risk.

“That drug (mifepristone) has resulted in the deaths of some women,” Armacost said, citing FDA reports. “We thought the doctor should at least see her and give her a physical exam.”

About 1.5 million U.S. women have used mifepristone between 2000 and 2011, the FDA reported. The agency said 14 women died after taking the drug, adding that it did not have enough information to attribute the deaths to the medication.

Previously, Planned Parenthood and Affiliated Medical Services already required medication abortion patients to come to a clinic for a physical exam and counseling 24 hours before an appointment to receive the pills. The patient was able to take the second pill from home, but both providers also scheduled a third visit to confirm the termination of the pregnancy.

This practice is out of step with FDA protocol, which recommends a patient take both pills at a medical clinic.

“Planned Parenthood is putting the health and safety of women in danger by not administering abortion drugs as advised by FDA regulations,” said state Sen. Mary Lazich, R-New Berlin, who sponsored the bill that became Act 217.

However, Planned Parenthood officials said the law goes beyond enforcing FDA protocol by requiring that the same physician be present for the first two appointments, and by leaving other standards unclear. The group’s lawsuit challenges two provisions of the law.

First, Act 217 requires the physical presence of a doctor when the medication is “given.” Broekhuizen, a plaintiff in the lawsuit, said it’s unclear whether the physician must be with the patient when she takes the second pill, traditionally at home. Violating this part of the law is a Class I felony, punishable by up to three and a half years in prison and a $10,000 fine.

Second, the law requires that the physician, under the threat of civil liability and a fine of up to $10,000, determine that the patient is not being coerced. But Broekhuizen said the law does not provide clear enough guidelines for doing so.

“I do not understand what is permitted and what is illegal,” Broekhuizen, a plaintiff in the lawsuit, wrote in a court document. “It is unclear to me what a physician must do to ensure compliance.”

Planned Parenthood already has a consent process in place, as mandated by Wisconsin law. It includes counseling about options for continuing or terminating a pregnancy and a 24-hour waiting period between this appointment and an abortion.

Samantha said that in addition to a medication abortion being available earlier, the procedure would have afforded more privacy. During her surgical abortion, she said, there were “six other people in the room,” including medical students.

“It was really overwhelming and obviously painful, too,” she said. “I really wish I could have had the privacy of being in my own room and dealing with just the people affected, just me and my partner.”

Abortions harder to obtain

Matt Sande of Pro-Life Wisconsin said the new law could help women come forward about being coerced into abortion. Photo courtesy of Matt Sande.

According to the state Government Accountability Board, the bill that led to Act 217 was opposed by groups including Planned Parenthood Advocates of Wisconsin, the Wisconsin Medical Society, the Wisconsin Academy of Family Physicians, and the Wisconsin Association of Local Health Departments and Boards.

Supporting the legislation were Wisconsin Right to Life, Pro-Life Wisconsin, Wisconsin Family Action Inc., and the Wisconsin Catholic Conference.

Matt Sande, director of legislative affairs for Pro-Life Wisconsin, said his group is pleased with the new law and not upset that providers in Wisconsin stopped offering medication abortions.

“We applauded that, naturally,” Sande said. “If Planned Parenthood and Affiliated Medical Services were to permanently suspend medication abortions, it would reduce the induced abortions in Wisconsin by approximately one-fourth.”

Sande said he hopes the law’s counseling requirements increase the chance that a woman will change her mind or reveal that she is being coerced if that is the case.

Providers say they already have a functional counseling and consent process, and that the law simply makes it harder for women to exercise reproductive choice, due in part to scheduling backups.

Vicki Saporta, president of the National Abortion Federation, of which Affiliated Medical Services is a member provider, said the burden is greater on women in rural areas, who have farther to travel to meet the requirements of the law. She added that this may result in some women not having abortions, and instead going through with pregnancies that place physical and mental health risks on the mothers.

“Sometimes, it could be the one more hoop they’re not able to go through,” Saporta said. “Most women are able to find a way, but some are not.”

A decade of abortions in the state:

Hover over the lines to see exact values.

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. This story was a produced in collaboration with Wisconsin Public Television.

All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

-

Legislators Agree on Postpartum Medicaid Expansion

Jan 22nd, 2025 by Hallie Claflin

Jan 22nd, 2025 by Hallie Claflin

-

Inferior Care Feared As Counties Privatize Nursing Homes

Dec 15th, 2024 by Addie Costello

Dec 15th, 2024 by Addie Costello

-

Wisconsin Lacks Clear System for Tracking Police Caught Lying

May 9th, 2024 by Jacob Resneck

May 9th, 2024 by Jacob Resneck