The City of Fresh Vegetables

New city program aims to turn empty lots into gardens grown by residents.

Tim McCollow, project manager of the Home Gr/Own initiative, speaks to Lindsay Heights residents weekly and encourages them to be creative when transforming city-owned vacant lots. (Photo by Scottie Lee Meyers)

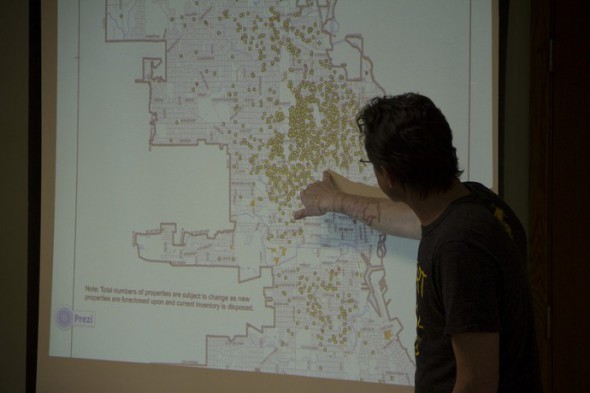

During a recent presentation at the Groundwork Milwaukee community gardening workshop, Tim McCollow pulled up a map of Milwaukee covered with thousands of colored dots representing city-owned foreclosures and vacant lots.

The image stood on the screen like an X-ray and the diagnosis didn’t look good. The city owns about 1,000 tax-foreclosed properties and 2,700 vacant lots, and those numbers are swelling. By the end of the year, the city plans to demolish 500 dilapidated houses, leaving empty spaces in its wake. McCollow, project manager of the city’s Home Gr/Own initiative, was there to offer a treatment plan.

McCollow said he presents to community groups several times a week, even now in the dead of winter, to offer city resources and inspire residents to turn the vacant lots — which typically measure 40-feet wide by 140-feet long — into gardens, orchards and compost sites. He’s encouraging people to be creative, noting that, for example, the city is seriously contemplating turning a foreclosed property into a mushroom grow house.

The city of Milwaukee is the reluctant landlord of about 2,700 vacant lots, most of which are marked with no trespassing signs. By the end of the year, city officials hope to convert 10 vacant lots into community gardens that will contribute fresh foods to their neighborhoods. (Photo by Scottie Lee Meyers)

“There really is no bad idea. Let’s activate these sites and reap all the subsequent benefits — from storm water harvesting, to neighborhood cohesion, to community engagement — so we can … start to change these neighborhoods,” McCollow said.

Most of those colored dots on the map are concentrated on the North Side, which is why Home Gr/Own is focusing most of its efforts in the Lindsay Heights neighborhood. “It’s one of our poorest neighborhoods; it’s one of our least healthy neighborhoods. But on the flip side, there’s some of the best human capital in the city working in that area,” said McCollow, referring to Walnut Way Conservation Corp., Fondy Farmers Market and Alice’s Garden.

A 2010 study conducted by the Center for Urban Population Health found that more than two-thirds of Lindsay Heights residents reported inadequate produce consumption, and one-third were obese.

The city wants the foreclosures and vacant lots off its hands. To ensure they fall into the right ones, the city uses a lease-to-own model, which officials say allows them to monitor for proper land use. “We want to build up trust and credibility with our partners before we hand them a piece of land in the middle of a neighborhood,” McCollow said.

Bruce Wiggins, executive director of Milwaukee Urban Gardens, is part of the group that hosted the workshop. The organization helps residents secure land and guides them through the necessary paperwork, while also providing liability insurance.

Wiggins said the average price for a one-year lease differs by neighborhood, but typically ranges from $100 to $500 per year. Residents also can sign up for a free seasonal growing permit, although he said that doesn’t protect the city from reclaiming the land after the permit expires to erect housing. Vacant land ownership requires aldermanic approval.

There are obstacles to be overcome in this effort, McCollow noted. While community gardens are nice, the city would prefer housing on the lots because that generates property tax revenue. “The aldermen and the city would love to have a house on every one of these vacant lots. You can’t deny that,” McCollow said.

Also, city ordinances are lagging behind the urban agriculture movement. “It’s against the law at this second to put up an accessory structures on a vacant lot, which is very unhelpful. People need sheds, people need rainwater harvest structures,” McCollow said.

Shaiya Morris, project coordinator for Home Gr/Own, said the Office of Environmental Sustainability is drafting a set of ordinances outlining zoning and permitting changes, as well as providing and enforcing clear-cut food policies so consumers can trust that spinach from a local garden would not have E. coli. She expects the ordinances will be ready for Common Council approval by July.

Morris said additional goals for the year include converting five foreclosed structures and 10 vacant lots to food-based uses.

“Now it’s our job to put the spotlight on these neighborhoods, especially Lindsay Heights,” Morris said. “We think if we can successfully do that and launch many of these projects, in the end we can bring life back to these communities.

This story was originally published by Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, where you can find other stories reporting on fifteen city neighborhoods in Milwaukee.

Good idea, city gets money, residents can grow whatever! But in my neighborhood the land is not used. The resident plants vegtables or flower or X but never takes care of the plants they die off leaving the land looking overgrown with weeds. The residents that rent the land may not live near-by and they forget about it. I think we should find a better way to manage this. Rent or lease the land to: resturants to grow produce, or landscapers to grow sod and flower, or christmas trees. What do you think?…

Good idea since tomatoes and peppers pay taxes! What the city should be doing is rebuilding homes on those sites. If they plan to turn every site into a farm bad idea, if they plan to use them as gardens in the meantime fine, and if they plan to turn every lot into a garden bad idea. We need to be rebuilding homes, increasing the density back into the north side. Gardens are a nice idea but they don’t pay taxes and is the northside eventually become a rural farm? A city cannot sustain itself on garden plots.

Redford! Why so negative? Gardens are only a “temporary” plan but I won’t live long enough to see housing on all those vacant lots, so why not do something now? And what could be more neighborly than growing things?

But why aren’t the ordinances ready now when seeds for summer gardens are being planted indoors to be transplanted outdoors MUCH earlier than July. Can someone fix that?