Stories from San Quentin Prison

Photography, writing and podcasts create a different kind of exhibit that captures life in prison.

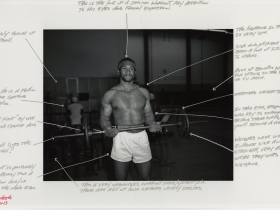

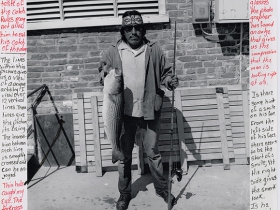

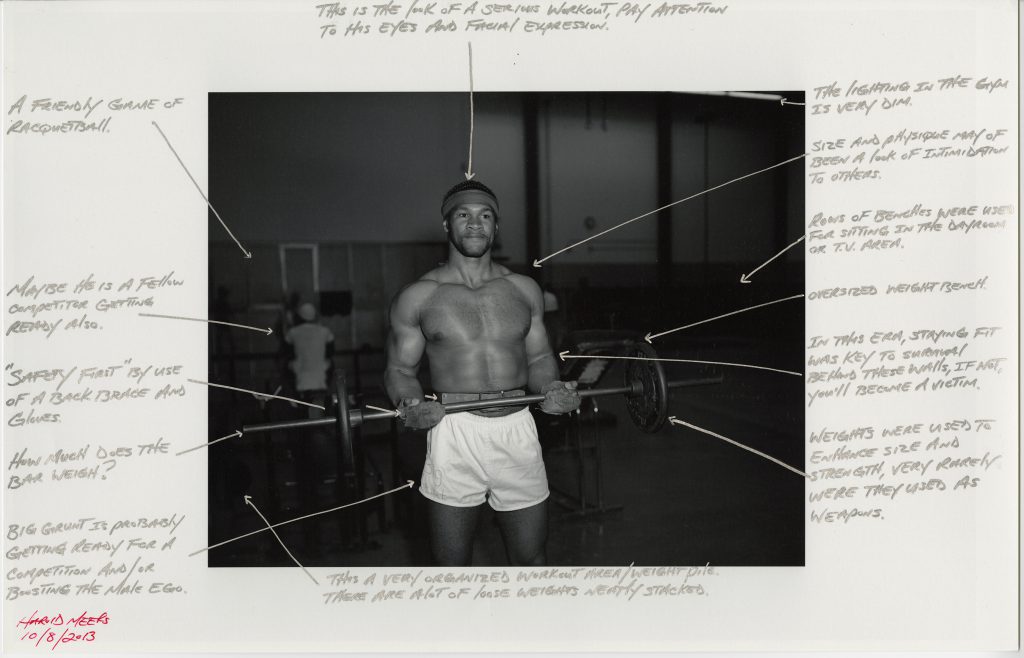

Harold Meeks and Nigel Poor, Gym Profile 7-15-75, 2013. Inkjet print and ink. Courtesy Nigel Poor, with thanks to Warden Ron Davis and Lieutenant Sam Robinson.

A prison may seem like an unlikely place to discuss art and photography, but artist Nigel Poor uses photos to encourage conversation, tolerance and understanding in her exhibit The San Quentin Project: Nigel Poor and the Men of San Quentin State Prison.

The show runs through March 10, 2019 at the Milwaukee Art Museum (MAM).

The exhibit illustrates “how art and storytelling can play a role in restoring dignity to incarcerated individuals,” said Josh Depenbrok, the museum’s PR manager.

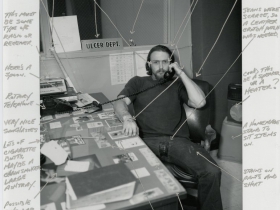

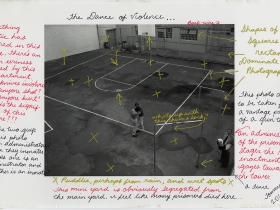

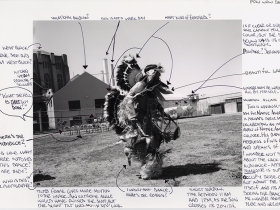

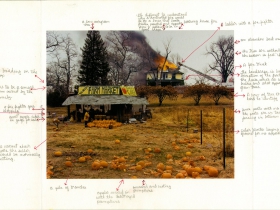

The first part of the exhibit highlights a mapping exercise, where inmates viewed photos and wrote down their impressions of the pictures. A handful of double-sided photos, enclosed in protective material, are hung in a circle so visitors can examine the photos and read the inmates’ perceptions.

Some inmates are quite candid about their background and the circumstances that led them to prison. For example, in response to a photo of a man working on cars, an inmate writes about growing up in the Crenshaw neighborhood of Los Angeles, getting involved in drug dealing, and experiencing police brutality.

He prefaces his experiences with, “This was how I spent my weekends, working on the cars of my wife’s girlfriends.”

“You are expressing how you see the world,” Poor says during a short video of her speaking to the inmates about the history of photography (and the roots of the camera obscura, dating back to 400 BC).

The second part of San Quentin is a series of black-and-white archival photos, taken during the 1960s and 1970s by several of the prison’s inmates and correctional officers, including Harold Meeks and Mesro Coles-El. The photos are divided into two sections, beginning with the fairly mundane (and sometimes domestic) aspects of prison life, including a group picture of the San Quentin schoolchildren, sons and daughters of the correctional officers, an inmate holding a seal, a prison wedding and the welding shop.

Several photos of inmates with their families on Mother’s Day are especially touching. These photos show the toll incarceration takes not just on inmates, but on their loved ones.

The second group of photos contains disturbing and graphic images illustrating the darker side of life behind bars—a pool of blood on the ground where a man was stabbed to death, a picture of cuts on the wrists of an inmate who attempted suicide, and depictions of various weapons confiscated within the prison.

Each inmate of the Marin County, California, prison (the oldest correctional facility in the state) has a different, and often interesting, perspective when it comes to the photos. Some are humorous; some angry; some matter-of-fact.

“How ‘bout those full hairstyles from back in the day?” someone notes of the ‘60s bouffant hairdos worn by women in a photo of the “San Quentin Angels,” volunteers who visited the inmates at the prison.

“RAGE,” writes one inmate of a 1971 photo depicting a man in his boxer shorts standing in the prison corridor, a defeatist look on his face, and hands clutched into fists.

The third part of San Quentin features several electronic stations where museum visitors can listen to “Ear Hustle,” a podcast recorded from inside the prison, created by Earlonne Woods (an inmate serving a 30-year sentence for second degree robbery) and Nigel Poor. Woods appears to have a thirst for knowledge and sharing stories.

While incarcerated, besides developing the podcast, he earned a degree from a community college and joined an association for journalists. A short video shows Woods interviewing another inmate for the podcast. With an easygoing manner and positive, empathetic attitude, Woods appears to be a natural interviewer.

“Ear Hustle,” which has achieved national recognition, chronicles daily life in San Quentin and inmates’ personal experiences from childhood. In one podcast, Tommy Shakur-Ross speaks about growing up in a strict Baptist household. Rebelling against his minister father, Shakur-Ross joined a street gang, a decision that would ultimately lead to his incarceration.

By blending art with sociology and psychology, The San Quentin Project proves that art can be objective and subjective, documentary-like and therapeutic. The exhibit humanizes those who are incarcerated by sharing their stories and inviting the public into their daily lives.

The San Quentin Project Gallery

The San Quentin Project, Through March 10, 2019, Milwaukee Art Museum.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits, all detailed here.

Art

-

It’s Not Just About the Holidays

Dec 3rd, 2024 by Annie Raab

Dec 3rd, 2024 by Annie Raab

-

After The Election Is Over

Nov 6th, 2024 by Annie Raab

Nov 6th, 2024 by Annie Raab

-

The Spirit of Milwaukee

Aug 30th, 2024 by Annie Raab

Aug 30th, 2024 by Annie Raab