Why Wisconsin’s a Magnet for Wild Animals

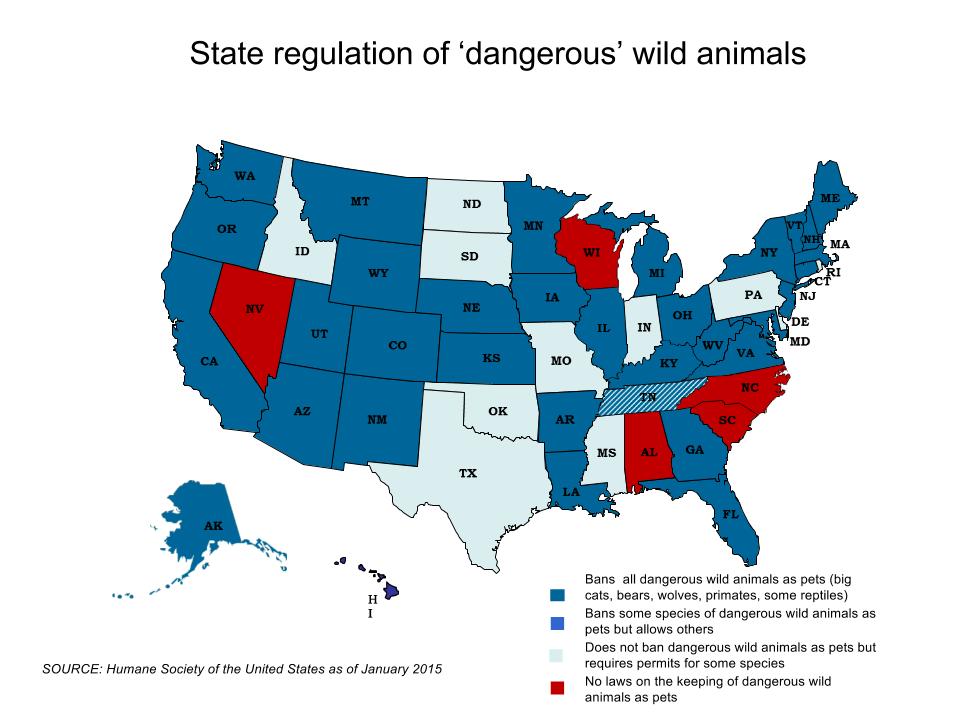

It's one of five states with no laws against keeping dangerous animals as pets.

Andy Carlson, who has volunteered at Valley of the Kings for about 20 years, leans in to speak to a tiger living at the sanctuary in Sharon. Carlson said many of the animals at Valley of the Kings have been caught up in the “underground market” of exotic animal trade. Some critics say Wisconsin’s lax exotic animal laws make the state a draw for smugglers. Photo by Grey Satterfield IV of Curb Magazine.

When Bekah Weitz’ phone rings, she never knows what is waiting for her on the other end of the line.During one of her shifts working animal control for the Eau Claire County Humane Association in 2005, a confused officer responding to a house fire in Dunn County called for backup after being tipped off that a shed attached to the burning house contained several pet cats — big cats.More specifically, tigers. And no one knew they were there prior to the fire.Weitz advised the officer not to act until she and other animal control officers arrived on the scene. If the tigers were to escape, Weitz said, they should be considered extremely dangerous and the officers should take action to defend themselves and those in the neighborhood if necessary.While en route to the scene, Weitz received another phone call from the officer: The tigers had been found, but all of them had died from smoke inhalation.Recalling the incident, Weitz — now a humane investigator for Monroe County — said that “as horrible as that was for them, it was probably the best case scenario for everybody involved because it didn’t mean that there were loose tigers in the area.”

Wisconsin is one of just five states that allow residents to keep almost any animal they want as a pet. The others are Alabama, Nevada, North Carolina and South Carolina.

And while the United Nations unanimously adopted its first resolution on July 30 to curb illegal wildlife trafficking, Wisconsin’s lax laws make the state a draw for animal smugglers, critics say.

The “lion-like” creature on the loose that prompted a massive police search in and around Milwaukee raised questions about the wisdom of allowing dangerous exotic animals to be kept as pets.

Wisconsin’s lax laws when it comes to exotic pet ownership make it a draw for smugglers, advocates of more strict regulation say.

Debbie Leahy, manager of captive wildlife protection at the Humane Society of the United States, said that it is easier for someone in Wisconsin to own a dangerous exotic animal, such as a tiger, than to own a native animal, including a white-tailed deer.

“In some cases, it’s easier to own a tiger than a dog,” Leahy added. “Many places will require the dog be registered and vaccinated. There is no such requirement for a pet tiger.”

And although there are some federal laws governing the sale, breeding, transportation and exhibition of exotic animals, critics say there are not enough inspectors to police the wild animal trade. Regulation also is fragmented among several state and federal agencies, allowing some repeat offenders to evade enforcement, records show.

A few municipalities in Wisconsin, including Janesville, do ban some exotic animals. Milwaukee does not have a ban on specific pets but does prohibit ownership of animals that have a known propensity to attack people, other domestic pets or animals.

An effort in the 2013-14 session to ban “the possession, propagation and sale of dangerous exotic animals” in Wisconsin failed to advance in the Legislature. A similar bill is being pushed again this year.

However, some animal rescue organizations say stricter legislation could prohibit ownership of common pets like lizards and small snakes. Dealers and breeders argue some exotic animals live longer in captivity than they would have in their native habitat.

As a humane investigator, Weitz’ primary duties are to handle animal neglect, cruelty and abuse complaints, most of which involve cats, dogs, horses and cows. But, since she works in Wisconsin, every so often she encounters exotic, often dangerous animals being kept as pets.

Weitz said that while she would like to see stricter rules regulating exotics in Wisconsin, she believes owners should be able to keep their exotics as long as the animals are well cared for and not a safety risk.

“No one’s going to be saying, ‘You can’t keep a Chinese water dragon in your home’ because that’s like a 2-inch lizard,” Weitz said. “What people are going to be saying is, ‘You can’t keep a crocodile in your home,’ you know? (Restricting) dangerous exotics is really the goal.”

Many animals, few inspectors

While there are no laws to regulate private ownership of exotic pets in Wisconsin, the U.S. Department of Agriculture issues permits to people who sell, handle or exhibit warm-blooded animals or use them in research.

Squirrel monkeys, such as this one seen in the Ecuadorian Amazon, are among the many exotic species allowed to be kept as pets by residents in Wisconsin. The state has few restrictions on owning wild animals that are not native to Wisconsin. Photo by Monica Hall of Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

Owners of deer parks, zoos, petting farms and wildlife parks are among those required to be registered or licensed.

USDA inspectors are supposed to conduct regular, unannounced visits to licensed or registered facilities to ensure animals are receiving proper veterinary care, being treated humanely and have clean, ventilated enclosures. Compliance with these minimum requirements is mandated under the Animal Welfare Act, according to Andrea McNally, intergovernmental affairs specialist for the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service in Washington, D.C.

“We use a risk-based inspection system to focus our resources, allowing more frequent and in-depth inspections at problem facilities and fewer at those that are consistently in compliance,” McNally said.

There are 193 active licensees and registrants in Wisconsin, and four inspectors assigned to the state, according to McNally. This number is too small, Leahy said, resulting in too few inspections being conducted — which, combined with the USDA’s cursory checks of potential licensees’ backgrounds, can let violations slip through the system, the national humane society said.

It can take repeated, serious violations for a license to be revoked.

White-faced capuchin monkeys are among several primate species allowed to be kept as pets in Wisconsin. Babies are sold in the United States for thousands of dollars each. Wildlife protection groups say monkeys, such as this one living in the Ecuadorian Amazon, should never be kept as pets. Photo by Monica Hall of Wisconsin Center For Investigative Journalism.

For example, it took 19 “willful” violations between 2009 and 2011 at Lakewood Zoo in the Oconto County town of Mountain for the USDA to take action against the zoo’s owner and operator, Casey Ludwig.

A complaint, filed in June 2014, cited Ludwig for several serious violations, including failure to provide “minimally adequate veterinary care” and for failing to allow inspectors into the facility. Ludwig also was cited for “failure to provide a tiger with sufficient food,” causing it to develop bone disease.

A judge concluded that Ludwig’s “willful” violations showed he was “unqualified to be licensed,” and revoked his license in January, which, McNally said, prevents him from applying for a license in the future. But Ludwig’s license had already expired at the end of 2011 — just over three years prior to its revocation — and the zoo had closed in 2012.

Leahy said the Ludwig case shows how “slow the federal agency is to act against chronic AWA violators.” When asked why the USDA took so long to act, McNally said cases involving serious AWA violations undergo additional legal review before a complaint is issued.

“The investigative and enforcement process does take time in order to gather the evidence required to proceed to prosecution,” she said.

Want to buy a tiger?

For Wisconsin residents, purchasing an exotic pet can be as easy as the click of a computer mouse.

On Exotic Animals For Sale, one can buy a breeding pair of wallabies for $5,500; a 3-week-old, bottle-fed black and white capuchin monkey that wears diapers and clothes for $6,800; an Arctic fox pup for $500; a two-toed sloth for $4,400; and a zebra filly for $5,000.

Weitz said part of her job involves patrolling websites for exotic animals for sale. On one occasion, she came across an alligator for sale on Craigslist in Wisconsin and reported it to authorities. But oftentimes, she said, they cannot take action because it is not illegal unless a municipality has an ordinance against it.

Even if USDA licensees do import exotic animals with the proper permits, Leahy said there is nothing to prevent them from giving animals to unlicensed individuals.

This three-toed sloth was returned to the wild in March at the Cuyabeno Wildlife Refuge in Ecuador after it was discovered being kept illegally as a pet in nearby Lago Agrio. Wisconsin is one of just five U.S. states that allow residents to own almost any type of exotic animal as a pet, including sloths. Photo by Monica Hall of Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

Leahy noted that Animal Haven Zoo in Weyauwega offered to give two tigers to an ABC 20/20 undercover reporter in 2012, which is not illegal. When asked for comment, Dawn Hofferber, co-owner of the zoo, said her husband Jim would have given the tigers to the reporter only if the reporter had a USDA license, which would have required a site inspection prior to the tigers’ arrival at their new home.

Hofferber later added, “We are a family-owned and run zoo and do not approve of a lot of what goes on in the animal world … we do everything in our power to help and save any animal that comes our way.”

Individuals also can obtain exotic pets by visiting animal auctions. USDA-licensed facilities in Wisconsin can and do legally consign various animals to the auctions. They include emus, ostriches and kangaroos, according to certificates of veterinary inspection provided to the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism by the state Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection in response to an open records request.

For instance, Mark Schoebel, the owner of Timbavati Wildlife Park in Wisconsin Dells and Animal Entertainments, a Neshkoro business that rents out animals for shows and fairs, has consigned some of his animals to the Lolli Brothers Livestock Market in Macon, Missouri, which Leahy said conducts the country’s largest exotic animal auctions.

A certificate dated April 6 showed that Animal Entertainments sent 14 exotic animals — including a 10-month-old crowned crane, an 8-month-old zebra and a blackbuck (antelopes native to India whose survival is considered “near threatened”) — to the Lolli Brothers market.

“Auctions are of special concern because they foster impulse purchases, and people with no qualifications whatsoever can purchase animals with especially complex needs,” Leahy said.

Schoebel failed to respond to repeated attempts to contact him over the previous two months. In a statement issued by his attorney Thursday, Schoebel said he is following all laws related to consignment of animals to auction. Schoebel said in the statement that he has never been accused of any “physical or psychological harm” to animals.

“I have been licensed by the USDA, who is responsible for animal welfare and care,” the statement said. “I have been in good standing with the department for many decades. … My life has been devoted to animals.”

However, Schoebel did have a run-in with law enforcement in the mid-1980s stemming from a federal investigation into wild animal smuggling. He pleaded guilty in U.S. District Court in Milwaukee to four counts of violating federal wildlife laws, paid a $1,000 fine and got four years of probation for failing to properly document or get permits to transport protected waterfowl, raccoons and 17 bears.

In his plea deal, Schoebel agreed to work with prosecutors to uncover illegal trafficking of animals.

Article Continues - Pages: 1 2

-

Legislators Agree on Postpartum Medicaid Expansion

Jan 22nd, 2025 by Hallie Claflin

Jan 22nd, 2025 by Hallie Claflin

-

Inferior Care Feared As Counties Privatize Nursing Homes

Dec 15th, 2024 by Addie Costello

Dec 15th, 2024 by Addie Costello

-

Wisconsin Lacks Clear System for Tracking Police Caught Lying

May 9th, 2024 by Jacob Resneck

May 9th, 2024 by Jacob Resneck