How Milwaukee’s Giant Anti-Poverty Agency Unraveled

Government agencies gave SDC big contracts even after it ended internal auditing.

The Social Development Commission’s main office sits empty in Milwaukee on the evening of June 28, 2024. The long-troubled agency in April abruptly shut down and laid off its entire staff, creating new holes in Milwaukee’s safety net. (Julius Shieh / Wisconsin Watch)

This story was produced and originally published by Wisconsin Watch, a nonprofit, nonpartisan newsroom, and WPR. It was made possible by donors like you.

The Social Development Commission was reeling from a scandal in 2013.

The federal government had flagged numerous deficiencies in how the Milwaukee anti-poverty agency managed the city’s Head Start early childhood development services. Federal officials picked another vendor to run the program, costing SDC a $22 million contract that cut its budget by more than half, eliminated 154 jobs and prompted the CEO to resign.

About a decade later, another scandal leaves SDC’s future in doubt. The organization’s leaders this spring acknowledged having “misallocated” funds for its home weatherization program, costing SDC a $6.7 million state contract that created ripple effects across its wider budget. The details echoed those from 2013 and earlier in SDC’s tumultuous history.

The agency in April abruptly shut down and laid off its entire staff, creating gaps in essential services for low-income Milwaukee residents. Former vendors and employees are still trying to collect payment for past work, and multiple SDC Board of Commissioners members have resigned. Whether the organization will ever reopen remains unanswered.

What caused SDC’s unraveling? The results of a state audit launched just before its closing should fill in some details. Already clear, however, is that SDC’s past leaders significantly weakened internal financial controls with little outside scrutiny.

State, county and city governments awarded SDC major contracts even after the organization eliminated its internal auditing department and board auditing committee, WPR and Wisconsin Watch found.

These actions should have raised red flags to any independent monitors, experts say. But few were looking at SDC’s broader operations. Wisconsin Watch and WPR could not locate a comprehensive government audit of the organization’s finances conducted before 1996, when dial-up internet was still popular and Mike Holmgren still coached the Green Bay Packers.

The Social Development Commission’s main office in Milwaukee is shown on June 28, 2024. SDC leaders acknowledge having “misallocated” funds for its home weatherization program, costing SDC a state contract that created ripple effects across its budget — details that echoed those from its tumultuous history. (Julius Shieh / Wisconsin Watch)

SDC additionally failed to update financial procedures or internal controls for more than 15 years, even after eliminating the role of internal auditor.

SDC was created by governments but functions outside of them. State, county and city statutes define the organization as an intergovernmental commission, with each government appointing board representatives. No government claims broader oversight authority.

Government officials told WPR and Wisconsin Watch they largely focused on how SDC executes contracts with their individual offices — rather than broader operations issues.

A Milwaukee County spokesperson wrote in an email: “there appears to be no statute or ordinance that directly assigns responsibility for monitoring SDC generally (to any entity – including the county, state, and city).”

“Who’s responsible for fixing this agency that is too big to fail?” asked Wyman Winston, who spent 50 years in community development, eight of them directing the Wisconsin Housing and Economic Development Authority.

State and local governments should intervene, regardless of how statutes delegate responsibility, he said, with the constitutional responsibility to protect residents’ welfare taking precedence.

“Why would you let this entity that serves the largest number of people in the state with critical services wither away?”

SDC shutdown was no surprise

Toni Hamelin learned of SDC’s closing on April 26, a Friday. That left her little time to plan the next Monday’s breakfast, lunch and dinner for up to 40 children at the child care center where she works.

SDC’s closing required her to arrive to work early to prepare meals including cabbage rolls, shepherd’s pie and chicken tacos — with nothing more than a crock pot, a roaster and a hot plate.

Hamelin said SDC’s shutdown wasn’t a surprise. The organization’s meal quality declined during her 30-plus years in child care, and SDC stopped sending infant formula over a year ago, she said.

“I’ve been questioning things for sure, six months, because things just didn’t seem the way they were,” Hamelin said in July.

But it took officials months longer to notice SDC again faced the type of trouble that clouded every decade in its history.

Decades of scandals at SDC

Controversy has surrounded SDC since the 1960s, when residents argued over whether it should supply birth control and discuss police brutality. Within a decade, the scrutiny focused less on politics and more on corruption and mismanagement.

Headlines in the 1970s described leaders using grant dollars for lavish trips, moving SDC money into private accounts and keeping abysmal records that prevented auditors from investigating the agency.

During the turmoil, SDC leadership in the 1980s eliminated an internal auditing position. The organization’s outdated financial procedures manual referenced the role for years after it no longer existed.

SDC cemented its scandal-plagued reputation in the 1990s.

The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported between 1993 and 1996 that SDC leadership tapped organization funds for resort stays for staff retreats, spent exponentially more on a board dinner for 285 people than a Thanksgiving dinner that served 295 seniors, hired an executive director who falsified items on her resume, lost key financial documents in a series of burglaries, spent $400,000 in grant dollars without approval on a suspended construction project and allowed 1 million pounds of food to rot in storage.

State and county auditors responded in 1996 by laying out three options for SDC: Close, become a part of an existing government office or make serious changes.

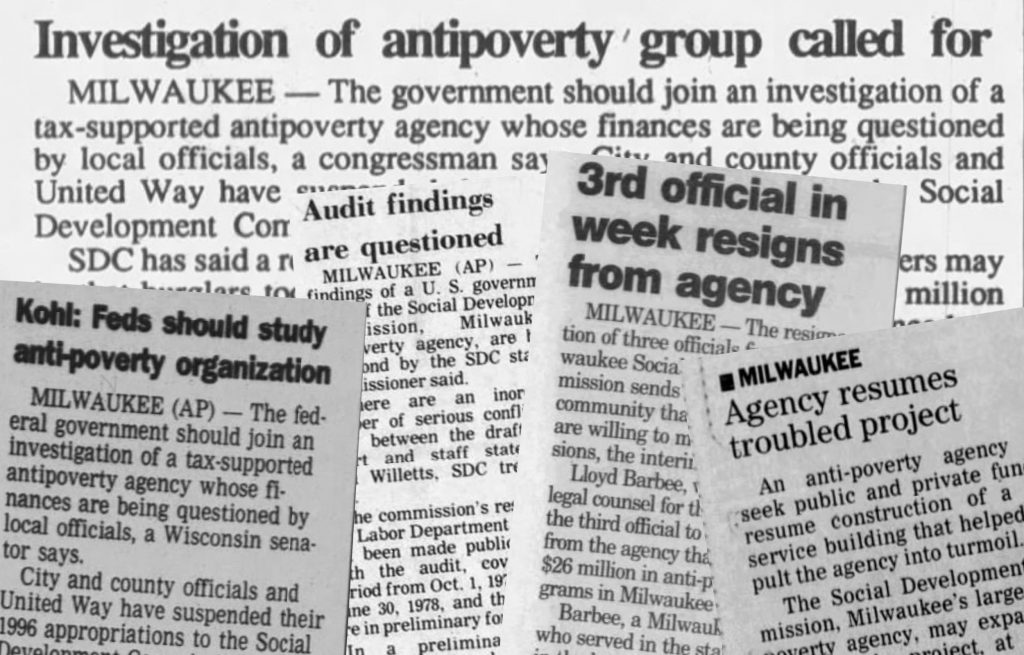

Clippings from the Associated Press and other newspaper wires describe controversies the Social Development Commission faced in past decades — echoing more recent problems that prompted its sudden closure in April 2024.

Following some recommendations, SDC cut its board from 24 to 18 seats, created a comprehensive budget and rehired an internal auditing staff.

Just a few years later, however, it couldn’t account for grant money to feed low-income children.

By 2011 complaints surfaced over SDC’s management of Milwaukee’s Wisconsin Works and Head Start programs. The organization within two years lost both contracts and roughly 70% of its budget.

That prompted SDC to fire its internal audit staff – eliminating the same positions state auditors previously recommended creating.

Just as in the 1980s, the organization failed to update financial procedures to reflect the change, state records show.

Questions about oversight

Weakened financial controls can make organizations more vulnerable to mismanagement or wrongdoing. Internal auditors serve a key governance role by offering objective views of an organization, said Mike Varney, the North American board chair of the Institute of Internal Auditors.

SDC’s internal audit team had caught serious issues, such as a lack of action around a $300,000 state weatherization grant in 2004. An internal audit just before the team was eliminated in 2013 revealed SDC was making inappropriate payments to employees.

Hearing that an organization removed internal auditing controls would “begin to raise red flags,” Varney said.

But SDC’s grantors didn’t seem overly concerned. Its government funding increased after the changes.

Even without internal auditing, the state still required SDC to contract an independent auditor to conduct an external audit, Tatyana Warrick, a Wisconsin Department of Administration spokesperson, wrote in a statement to WPR and Wisconsin Watch.

“The absence of an internal audit director should not be conflated to suggest there is a total absence of internal controls in that organization.”

Pandemic brings big contracts and big deficits

SDC faced a stress test in 2020 as time-limited federal pandemic dollars poured in, more than doubling its budget.

Its problems quickly snowballed. The organization’s balance in 2022 decreased by more than $600,000 — just under the combined worth of the 12 grants it was denied that year. In 2023, SDC lost out on 16 grants worth $16 million, board minutes show.

Attorney William Sulton, who voluntarily provides legal counsel to SDC, said the organization’s former CEO George Hinton and former Director of Finance Patrick Kirsenlohr failed to act. They should have known about the financial problems but never acknowledged the full scope of the problems to the board, he said. Neither Hinton nor Kirsenlohr responded to requests for comment.

Still, minutes from monthly board meetings in 2022 and 2023 show Kirsenlohr told the board that SDC would need to slice its administrative budget in half in 2024, that a food service program was operating at a $250,000 loss and that SDC sought a $1.5 million loan to help cover expenses. (The board did not approve the major loan application and lacked a procedure to do so, Sulton said.)

The board should have had better practices, Sulton said. But members likely lacked expertise to pick up on warning signs from SDC management, he added.

Around that time the board voted to eliminate its audit committee, typically a mechanism for members to learn about organizational finances and ask questions without management’s influence.

The board dissolved the committee because it never met, board chair Barbara Toles said, noting it happened before she joined.

Sulton questions how helpful the committee could have been had it met. No one on SDC’s all-volunteer board had accounting expertise, he said.

Barbara Toles, who chairs the Social Development Commission’s Board of Commissioners, presides over a board meeting at Port Milwaukee on Sept. 11, 2024. SDC’s latest trouble came from trying to continue programs it couldn’t afford after budget cuts, she says. (Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

Government grantors miss problems

Government grantors are required to monitor and report on their contracts. But they didn’t catch SDC’s fundamental vulnerabilities either until noticing SDC missed payments to some of its contractors.

As a recipient of more than $750,000 in federal funding, SDC was required by the federal government to commission an annual external audit. CliftonLarsonAllen conducted the most recent audit, which examined 2022. SDC submitted it past a deadline. Auditors found no issues with SDC’s controls or financial reporting.

But year-in-review audits can’t stop financial missteps in real time.

And one report can’t always catch every issue simmering at lower levels of an organization as large and complex as SDC, said Brian Mayhew, executive director of the Center for Financial Reporting and Control at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Who should have monitored SDC?

No other organization like SDC exists in Wisconsin.

SDC’s dual titles make it hard to determine who oversees it.

A 1996 audit lists the city and county of Milwaukee as two of SDC’s founding entities. Meanwhile, state statutes give local governments authority to fund commissions like SDC.

Asked if the city of Milwaukee had monitoring authority over SDC, Jeff Fleming, a spokesperson for Mayor Cavalier Johnson, said no.

“SDC was intentionally structured so as not to be part of city, county or state government,” Fleming told Wisconsin Watch and WPR. “With that autonomy comes an independent obligation to manage funds and programs.”

The federal government designated an office to oversee community action agencies. But in 1981, President Ronald Reagan eliminated that office and designated states to pass federal dollars to community action agencies like SDC.

The decentralization of social welfare programs makes it harder to track taxpayer dollars, said Ryan LaRochelle, a senior lecturer at the University of Maine’s Institute for Leadership and Public Service.

“As you give more authority to the states, which are even sometimes less administratively capable than the federal government, it just gets really, really difficult.”

The Social Development Commission Board of Commissioners meets at Port Milwaukee on Sept. 11, 2024, in Milwaukee. SDC commissioners are continuing to meet about the anti-poverty agency’s future, which remains unclear after it abruptly shut down in April. (Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

The inclusion of government officials on the SDC board offers some opportunities for scrutinizing the organization, but having so many other organizations appointing board members complicates accountability efforts.

Auditors in 1996 recommended that SDC trim some of the 11 appointing organizations and the eight elected board seats at the time.

“It has been suggested that with so many appointing entities, none can be responsible for the performance of the agency as a whole, and public accountability is undermined,” auditors wrote.

That audit prompted the agency to cut six board seats, but by 2022 the number of appointed members rose to 12. Today, five of those appointing agencies have not filled their seats on the board, leaving the agency with 10 members to repair SDC.

Representatives of each government typically focused mostly on SDC’s contracts with their organization.

While the Wisconsin Department of Children and Families performed on-site reviews of SDC at least once every three years, other holistic reviews were less frequent. The Legislature and the county could have ordered comprehensive audits of SDC’s operations, but neither has exercised that power in more than two decades.

State Rep. Robert Wittke, R-Racine and a co-chair of the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, said the committee has not received requests to investigate SDC since its closure and has “been busy with a number of other things.”

His fellow co-chair, Sen. Eric Wimberger, R-Green Bay, wrote that accusations of fiscal mismanagement at SDC “raise major questions regarding this and similar quasi-governmental entities.”

Some SDC leaders seemed to view government oversight warily. The organization’s 2019-2024 strategic plan lists government oversight as one of three threats facing the organization, alongside state politics and SDC’s “sketchy brand.”

What happened this time?

SDC’s latest trouble came from trying to continue programs it couldn’t afford after budget cuts, said Toles, the SDC board chair. Rather than scaling back operations, executive leadership tried to move funds around — using grant dollars for one program to cover costs for another following accounting errors.

“And that’s a no-no,” Toles said. “Never do that.”

When that practice began is unclear, but by late 2023 the Wisconsin Department of Administration noticed SDC’s weatherization contractors weren’t getting paid on time. The agency terminated the weatherization contract in March and launched an audit into that SDC program.

“It really is an example of state administrators and the tools that state administrators use actually working as they’re designed to work,” said Cheryl Williams, executive director for the National Association of State Community Services Programs.

The cancellation eliminated more than one-fifth of SDC’s proposed 2024 budget and prompted layoffs of one-third of the agency’s staff. The final blow came when Hinton, before he resigned as CEO, told the SDC board that the agency couldn’t make payroll.

SDC wasn’t the first Wisconsin social service organization to lose a state weatherization contract due to mismanagement. Two others lost contracts in past years. SDC’s weatherization program grew in 2005 after another Milwaukee-based organization lost its contract.

The Social Development Commission’s main office in Milwaukee is shown on June 28, 2024. (Julius Shieh / Wisconsin Watch)

What’s next for SDC?

Hamelin, the child care director, learned about SDC’s closing on the same day the organization’s employees did.

Hamelin for three months struggled to afford the extra costs of buying three meals a day for Bright Rainbow Academy kids. She considered raising rates for parents, but another local organization stepped in to provide meals before that was necessary.

Bright Rainbow isn’t the only organization to move on since SDC’s closure.

Grantors at the state, county and city level told WPR and Wisconsin Watch they already reallocated funding previously pledged to SDC. At least three agencies plan to decide on next year’s grant before the end of the year.

Reopening will only become harder the longer SDC’s programs remain paused.

Back during the scandals of the 1990s, state auditors wrote that no one could anticipate the consequences of an SDC closure.

Winston, the former community development official, said Milwaukee residents still need the vital services SDC provided.

His recommendation: “Look at what occurred, fix it, make sure it gets reestablished and that there are protections to make sure this doesn’t happen again.”

Meredith Melland, a reporter with Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service and Report for America corps member, contributed reporting.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

Political Contributions Tracker

Displaying political contributions between people mentioned in this story. Learn more.

- January 12, 2016 - Cavalier Johnson received $100 from George Hinton