Milwaukee Dredging Project Could Have Extra Benefit

Estuary cleanup effort could release nutrients that boost Lake Michigan perch.

Drone photo of Milwaukee’s inner harbor. Floating orange booms along the Milwaukee River during the 2023 We Energies dredging project are visible. The contaminated dredged materials from the river bottom were piped to the Confined Disposal Facility. WCMP did not fund the drone photography, which is used with permission. Photo by @Eric Halvie.

It started with a mystery: What were those green, hair-like tufts clogging nets pulled up from the Milwaukee harbor?

Fisheries biologist Aaron Schiller wondered if what stuck to the small squares of Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) sampling nets in summer 2023 was Cladophora, foul-smelling algae known for washing up on beaches in late summer and early fall.

Drs. Carmen Aguilar-Diaz and Russell Cuhel, senior scientists at the UW-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Sciences, doubted it was Cladophora, and as it turned out, it wasn’t.

So what were these algae?

“They brought us a little slime from their nets and it turned out to be these really long, centimeter-long ribbons of diatoms, which are beautiful juicy steaks of the food web,” Cuhel said. “They’re loaded with lipids and protein and because they grow so long, they were actually clogging the gill nets of the DNR and the fish would come up and they would see ‘em and swim around.”

Clogged nets made it difficult for WDNR to sample fish, but the diatoms could be a boon for young fish that eat them.

And these diatoms were exceptionally abundant—showing up at a concentration and location that surprised Aguilar-Diaz and Cuhel with their almost 30 years of studying Lake Michigan and the Milwaukee harbor.

What are diatoms?

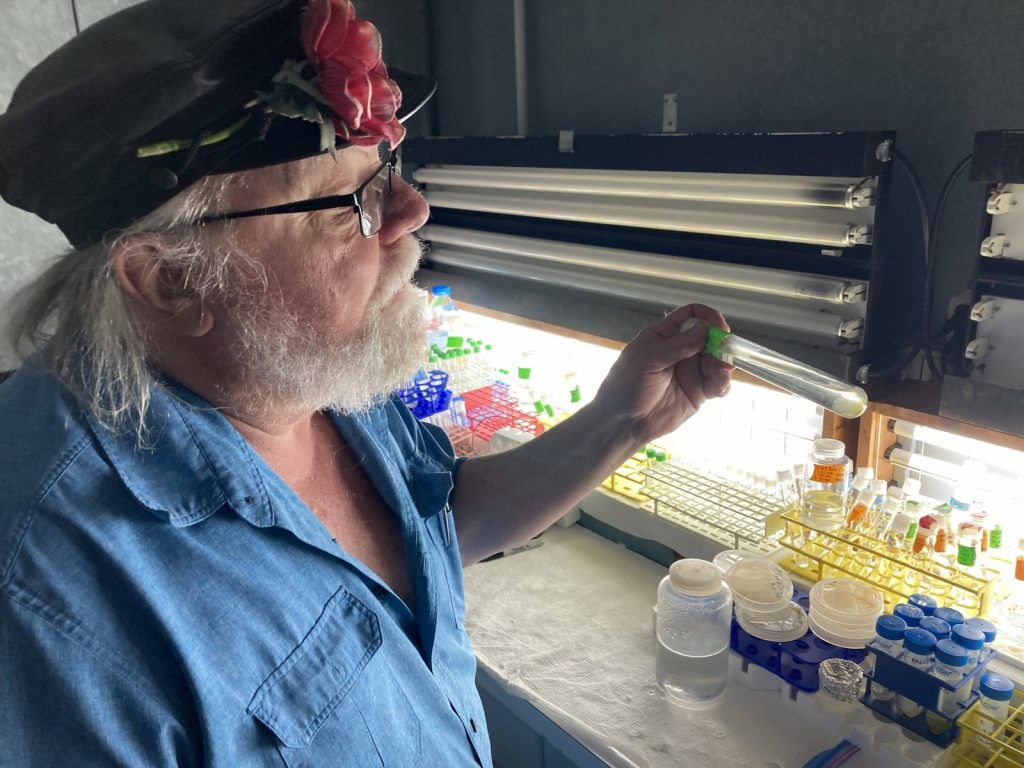

Dr. Russell Cuhel holds a diatom sample in the cold room of his lab at the UW-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Sciences in April 2024. Cuhel likes to call diatoms the “juicy steak of the food web.” They are nutritious for young fish. Photo by Michael Timm.

One of many different types of algae, diatoms are microscopic organisms with “houses” made of silica, the same mineral composing sand or glass. Like most algae, diatoms photosynthesize just as terrestrial plants do, hence their green color.

Rich in fats and protein, diatoms make great food for larval and juvenile yellow perch—of Milwaukee fish fry fame. Beneficial blooms of these algae can give the aquatic food web an energy boost.

But since invasive mussels altered the food web, Lake Michigan diatom blooms declined. The scientists wondered: could those found in Milwaukee’s harbor be responding to a new source of nutrients?

Finding the diatoms coincided with the first phase, in 2023, of dredging to remove contaminated river sediment from the Milwaukee Estuary Area of Concern — the inner and outer harbor of Milwaukee and lower parts of its three rivers, designated as areas of concern because of their pollution. This initial dredging mainly dug up polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) related to We Energies’ historic coal gasification plant in the Third Ward.

The Waterway Restoration Partnership, which includes WDNR, We Energies, and others, banded together to clean up this river muck. Their goal is to remove legacy carcinogens that lead to fish tumors and consumption advisories, in short: to make our waters “fishable and swimmable.”

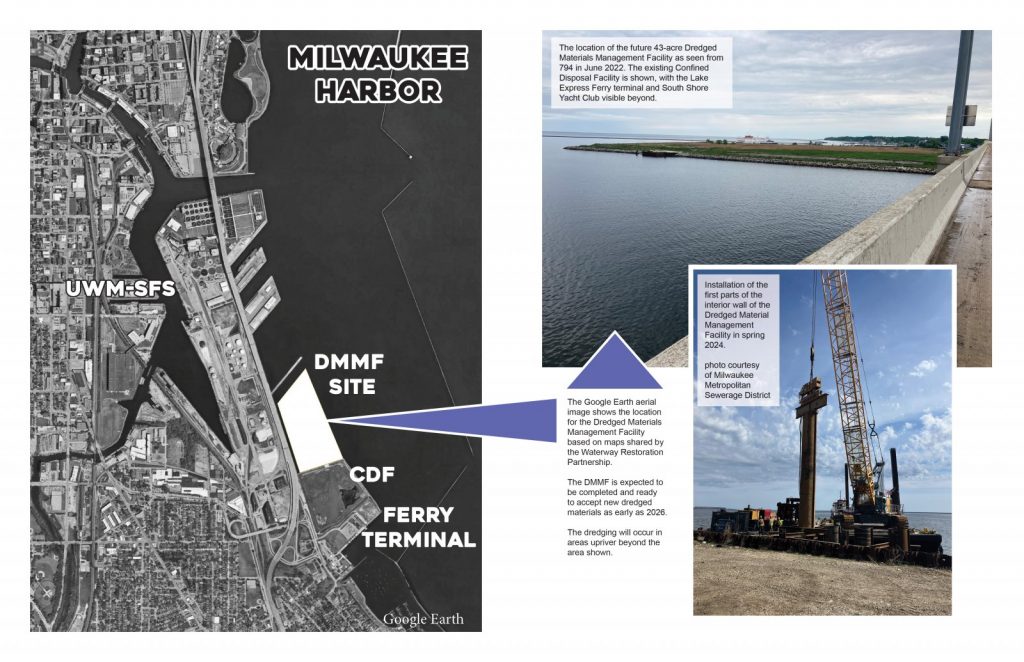

The main dredging is not expected until at least 2026 when a facility to hold the removed solids is completed. Construction on this “Dredged Materials Management Facility,” or DMMF, began in spring 2024. When completed, the 43-acre holding area is intended to sequester years of sediments dredged from Milwaukee’s river bottoms.

The Google Earth aerial image shows the location for the Dredged Materials Management Facility based on maps shared by the Waterway Restoration Partnership. The DMMF is expected to be completed and ready to accept new dredged materials as early as 2026. The dredging will occur in areas upriver beyond the area shown. | The top photo shows the location of the future 43-acre Dredged Materials Management Facility as seen from 794 in June 2022. The existing Confined Disposal Facility is shown, with the Lake Express Ferry terminal and South Shore Yacht Club visible beyond. | The bottom photo shows installation of the first parts of the interior wall of the Dredged Material Management Facility in spring 2024. Map illustration by Michael Timm. Top photo by Michael Timm. Bottom photo courtesy of Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District

But the Third Ward sediments dredged in 2023 were deposited into the existing Confined Disposal Facility north of the Lake Express ferry terminal.

When a slurry of dredged sediments like these is deposited, it is “de-watered.” That water is treated to remove regulated contaminants before being returned to Lake Michigan.

In the lab, a grad student working with Aguilar-Diaz and Cuhel simulated the dredging process and found the “leachate” water was rich in ammonia. The scientists wondered if this nutrient could be related to the unusual surge of diatoms observed.

To pursue the mystery, they conducted fieldwork aboard the R/V Neeskay, UW-Milwaukee’s research vessel. Throughout 2023 and 2024 the scientists and their students made more observations and hypothesized connections.

They found compelling though not conclusive evidence of a connection.

“We found anomalous concentrations of ammonia and nitrite and phosphate near the disposal site where the sludge from the dredging was being de-watered, and that area was richer in nice, juicy-steak-of-the-food-web algae, and it continued to be that way all summer long, and now,” Cuhel said. “So, the question is: Did the dredging stimulate them or was it something else?”

Whatever the cause, diatom blooms could constitute a movable feast for young native fish that anglers and society at large care a great deal about bringing back from the brink.

Diatoms are not to be confused with a “harmful algal bloom” of cyanobacteria, different toxic algae that capture headlines.

Cuhel said the shape of Milwaukee’s harbor makes toxic blooms here unlikely. That’s because cyanobacteria tend to dominate only when nutrient-rich waters are both warm and calm for an extended period. Lake Michigan and Milwaukee’s harbor generally have too much wave action and current to favor cyanobacterial blooms—though the area near the proposed disposal facility is relatively protected and could grow stagnant under certain weather conditions.

Drone photo of Milwaukee’s outer harbor showing the main (center right) and north (far left) harbor gaps. The different color of the water reveals its different properties inside and outside the breakwater. WCMP did not fund the drone photography, which is used with permission. Photo by @Eric Halvie.

This same area could be near where future dredge spoils are de-watered, so their observations led the UW-Milwaukee scientists to conversations with WDNR about potential harbor food web impacts.

In spring 2024, Aguilar-Diaz and Cuhel connected with WDNR’s Brennan Dow, Milwaukee and Sheboygan Area of Concern coordinator, and Rae-Ann Eifert, Lake Michigan monitoring and sediment coordinator. Both are graduates of the UW-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Sciences.

The DMMF’s water treatment plant will be designed to meet regulatory criteria, Eifert said, and discharges will need permits managed through WDNR. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and its contractor will ultimately be responsible for performing the cleanup and designing the DMMF treatment system, Dow said. Its final design is to be determined and could be informed by the work of the Milwaukee scientists and greater attention to nutrient impacts.

Understanding how dredging impacts Milwaukee could have implications for other harbors, Dow said.

“I mean, we’ve been dredging our harbors in Lake Michigan for a long, long time, and some of them haven’t been dredged in a while. So, they might be similar to Milwaukee in the case where you have a lot of organic matter that hasn’t been touched in a few decades,” Dow said. “And if dredging that up can release more nutrients and cause a temporary effect or something, it’s good to know so we can manage expectations with the public about what they may see in the environment.”

He and Eifert agreed that more research is needed to tease out causes of the higher diatom densities.

Another mystery puzzle piece was Eifert’s unrelated sampling cruise that confirmed Milwaukee’s 2023 diatom surge—extending eastward miles into the lake from the harbor—was unique along western Lake Michigan.

“One of my surveys was going all the way up and down the coastline of Lake Michigan,” Eifert said. “It does seem like they [diatoms] were more concentrated near Milwaukee, so there could be something going on there. We know that the dredging occurred that year, but it was also a weird year for a lot of other things [including the Canadian wildfires and associated smoke particulates]. So, it’s really hard to pinpoint exactly why the diatoms appeared that year, but if it is related at all to dredging, it’s good to know.”

How the mystery ends will depend on future research. Meantime, based on the bumper crop of diatoms observed that sometimes color Milwaukee waters with an olive hue, Cuhel predicts Milwaukee’s young perch will do well in 2024.

In May 2024, the scientists were excited that a recent research cruise already turned up ribbons of diatoms an impressive eight miles offshore. And at a May 2024 School of Freshwater Sciences research symposium, two of their students presented different aspects of their lab’s harbor research.

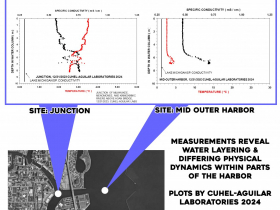

Undergraduate John DeTuncq studied how wind conditions and the physical harbor structure impact where and how nutrients feeding harbor diatoms move.

Grad student Mary Larson painstakingly isolated the diatom Tabellaria from field samples and exposed it in the lab to simulated day/night cycles. In the presence of enough nutrients, the diatoms kept growing and reproducing even in the absence of light.

For the summer 2024 field season, Larson plans to sample the harbor water column to observe what specific depths different algae prefer. Combined with knowledge and observations of the mixing and stratification of different water layers from the rivers and the lake, this could provide clues as to which algae benefit most from any influx of nutrients.

Aguilar-Diaz and Cuhel hope to do more research to predict how the harbor food web may respond to the dredging.

“We want to take mud from different areas of the Area of Concern and squeeze the water out of it,” Cuhel said. Then, in the lab, they would use that water to enrich algae cultures grown in water samples collected from the harbor. The scientists predict this will stimulate the same kind of algal blooms found during the 2023 dredging. If it does, this means they can probably expect the influx of more nutrients into the harbor as the major dredging work commences.

That would be “a nice resource for the food web,” Cuhel said. And a feast for the lake’s perch.

Photo Gallery by Michael Timm

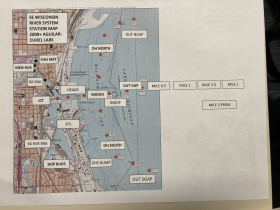

Maps and Data

Story by Michael Timm, a Milwaukee Water Storyteller for the nonprofit Reflo, who did our earlier series on reintroducing the sturgeon into the Milwaukee River.

This project is funded by the Wisconsin Department of Administration, Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration under the terms and conditions of Wisconsin Coastal Management Program Grant Agreement No. AD239125-024.21. Funded by the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office for Coastal Management under the Coastal Zone Management Act, Grant # NA22NOS4190085

Thank you for the thorough and informative article. Hoping for good things for the river and lake!

Gonna be a lot of work / time but excited for the final product of a safer cleaner river