Climate Justice in the Lincoln Creek Greenway

Activists and neighborhood residents seek to restore urban tributary.

Detaya Johnson and Catie Petralia, left, gather walkers on the Lincoln Creek pedestrian bridge on March 9, 2024. Photo by Michael Timm.

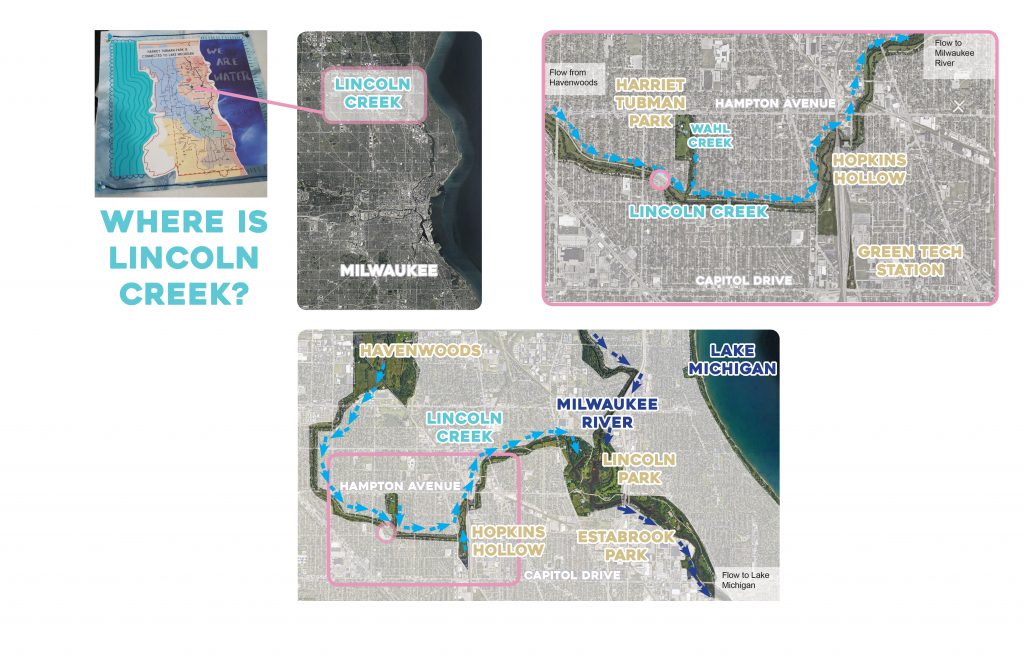

Climate justice was the topic for a day of programming in the neighborhoods surrounding Lincoln Creek, which flows south from Havenwoods State Forest, then east from 64th Street all the way across the city to Lincoln Park. There the urban tributary drains into the Milwaukee River adjacent to habitat improvement projects supported through the Waterway Restoration Partnership.

About 30 people gathered at Harriet Tubman Park, near 47th and Hampton, on a brisk but sunny Saturday on March 9, 2024 to celebrate the legacy of abolitionist Harriet Tubman. Speakers connected the current struggle for urban environmental justice with the story of the American freedom fighter. Tubman freed herself, then led scores of enslaved people to freedom along the Underground Railroad.

Detaya Johnson, program director at Nearby Nature, co-led the walk with Catie Petralia, volunteer coordinator at the River Revitalization Foundation.

Nearby Nature is a nonprofit environmental justice and equity initiative. “Recognizing a great need in neighborhoods stressed by high poverty and injustice, the group focuses its efforts in Milwaukee’s 30th Street Corridor and Lincoln Creek Greenway,” according to the group’s website. River Revitalization Foundation is an urban land trust known for stewarding the Milwaukee River Greenway. It is currently undergoing a merger with the Ozaukee-Washington County Land Trust.

Johnson and Petralia led walkers along the drainageway known as Wahl Creek, named for Christian Wahl, the “grandfather” of Milwaukee’s parks system. Harriet Tubman Park was named Wahl Park prior to renaming in January 2021. The straight-and-narrow concrete-lined channel conducts flows south over City of Milwaukee property along the eastern edge of the Tubman Park. The creek then flows behind private residential properties and empties into Lincoln Creek, which flows across properties owned by Milwaukee County and Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District.

Where Wahl Creek’s waters enter Lincoln Creek it transitions from concrete-lined banks to rock and cobble.

“And so I want you to make that parallel as we’re walking in this neighborhood,” Johnson said. “When we think about that generational trauma that gets passed down, but then you make that connection to a lined channel [that] isn’t free, that’s hindered from its best potential from doing its best. But when you see the naturalized area, when it’s allowed to be itself, when it’s allowed to range free and how beautiful that is.”

The walkers turned south of Glendale Avenue, traversed broken glass on the N. 46th Street sidewalk, greeted curious neighbors, and stepped into the sunlight at Lincoln Creek and its “greenway,” a contiguous stretch of public-owned land along the creek rehabilitated by multimillion-dollar MMSD flood management projects from the late 1990s into the 2000s.

The Lincoln Creek Greenway depicted on a Google Earth basemap. The water’s flow direction is shown by arrows. The circle notes the pedestrian bridge near 49th and Congress. Artist Melanie Ariens prepared artistic maps of Milwaukee’s watersheds highlighting Harriet Tubman Park. Wahl Creek is shown on the inset map. Map illustration by Michael Timm.

Maria Chilbert attended the walk to learn more about the Milwaukee River and its tributaries.

“Learning the history with the concrete lining and how they’re taking that away and how actually it’s helping to prevent flooding. So that’s interesting. And how they’ve got other projects in the city to help with preventing pollutants getting into the water,” Chilbert said. “I think it’s beneficial to learn these things about our community.”

Concrete removal in Lincoln Creek was motivated by protecting homes and businesses from floods, and the new rock-lined channels also provided pools and riffles for fish passage. And fish are now finding the creek.

Felice Green, director of programming with the nonprofit Milwaukee Water Commons, on her phone showed a November 2022 video of coho salmon swimming upstream in Lincoln Creek near Hopkins Hollow, the naturalized area a few blocks to the east where Lincoln Creek bends north after flowing beneath Hopkins Street near 35th and Congress. The salmon, splashing in the rocky shallows, are a species stocked annually by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

Back at Harriet Tubman Park, Melanie Ariens, Milwaukee Water Commons’ creative arts manager, organized an art collage activity to help participants visualize the continuous interconnection between Wahl Creek, Lincoln Creek, the Milwaukee River, and Lake Michigan. Ariens prepared colorful paper maps highlighting the Milwaukee-area river watersheds, with a star showing Harriet Tubman Park.

This sense of connection is important, said Cheri Briscoe, a longtime parks advocate for whom the walk was her first time visiting Harriet Tubman Park.

“I’m glad I’m here. This park is so much bigger than I’ve realized, and there are so many things that can be done with it. I am delighted that Nearby Nature has brought more focus into our—for lack of a better word—inner city, our more interior parks. We need to bring more focus into our more urban parks.”

Tracing the path of waterways connecting to the Great Lakes echoes the journeys of escaped slaves seeking freedom in Canada, said Petralia, especially after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 made even northern states like Wisconsin, where slavery was illegal, unsafe.

Two state representatives who joined the walk also participated in an afternoon panel discussion, “Climate Justice, Our Planet, Our Survival,” held at the Villard Square Branch of the Milwaukee Public Library.

Rep. Darrin Madison (D-10) and Rep. Supreme Moore Omokunde (D-17), whose current legislative districts both include parts of Lincoln Creek, joined Hanan Ali and Dr. Russell Cuhel on the panel.

Rep. Darrin Madison, Rep. Supreme Moore Omokunde, and Dr. Russell Cuhel on March 9, 2024. Photo by Michael Timm.

Poet Shana Wilson, who performs with the name Blue Lotus, offered opening remarks after producing a meditative tone on her singing bowl named Sun.

“Mankind has abused free will to the point where it’s a struggle to even be able to tell the seasons apart,” said Wilson. “We unconsciously vandalize and violate God’s art and come up to the very edges of Revelation. A revolution is long overdue… Why continue to disrespect God’s masterpiece when we ourselves are part of it and we have the resources to support the planet in healing itself? ‘Now’ is what we have, and we can’t just keep ignoring the signs.”

Johnson was inspired to organize the climate panel after a planned snowshoe event for February 2024 fell through due to lack of snow. This winter was Wisconsin’s warmest on record.

The panelists responded to a series of questions for almost two hours before an audience of 16.

Ali teaches environmental science at Bradley Tech High School and works as a land steward with Nearby Nature. She shared her research assistantship experience with Clean Wisconsin where she used maps to consider sustainable agriculture options for Wisconsin’s changing climate. She mentioned Aronia berries, American hazelnut, and perennial grain Kernza, crops which could help farmers address chronic soil loss.

“This relates to food insecurity, also relates to food deserts as well. So even though I was looking at the whole of Wisconsin, this raises the question of our food prices. We are the common people. We get the biggest hit whenever crops go down. If climate change occurs the way it’s going to occur,” Ali said, “what kind of crops are we going to have in the future?”

Dr. Cuhel, a scientist at the UW-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Sciences, has been studying natural aquatic environments for 52 years, working on Lake Michigan for 29 years. “I have been around long enough to understand change,” Cuhel said. “I want to get across this concept: To understand change you must know what was there before.”

Working with Dr. Carmen Aguilar, Cuhel said much of their work is “research education” where students help generate long-term data for Lake Michigan. “Instead of going to a lot of places once, I went to the same place over and over and over again,” Cuhel said.

From 1990 on, students have joined Aguilar and Cuhel on research cruises aboard the R/V Neeskay in the Milwaukee harbor and Lake Michigan, collecting samples and taking measurements. Each student group recorded data points noted in their own color. “They would see what we saw as continuous cycles with change imposed, but they would see that some of the points were ones they made or their friends made,” Cuhel said. “And to them that was huge.”

Representative Moore Omokunde pointed to his time as the county’s representative on the City-County Task Force on Climate and Economic Equity, which led to Milwaukee’s Climate & Equity Plan and its “10 Big Ideas” formally adopted by the city in 2023.

“We need to make sure that we’re doing the type of jobs that are going to hit the communities that are most affected by climate change, like Black and brown communities,” said Moore Omokunde. “We’re figuring out what kind of jobs there are, what kind of transitional jobs we need to create, and who needs to be able to do that work and how are they going to be able to do that work?”

Moore Omokunde said he tells skeptical constituents that climate change worsens pocketbook, safety, and stability concerns ranging from potholes and crime to health issues like asthma and freeway congestion.

“All of these challenges that you think are more important are only exacerbated by climate change,” Moore Omokunde said. He invited interested citizens to join Our Future Milwaukee, a coalition advocating for full plan implementation.

He also implicated capitalism as the problem, arguing systemic change is needed. “We can’t recycle our way out of climate change…” Moore Omokunde said. “Large corporations have to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. Also, we have to change the way we deal with transportation.”

Rep. Madison, who described himself as an “open socialist in the Legislature,” said environmentalism was baked into his path as an organizer to his first term serving in the State Assembly.

“It started at the Urban Ecology Center here in Milwaukee. And then I worked for the U.S. Forest Service for a period of time. Then went to Howard University where I majored in biology and then came home, worked for the Urban Ecology Center again, then the City of Milwaukee’s Environmental Collaboration Office, launching the Eco Neighborhoods Initiative, in which Lindsay Heights is our first Eco Neighborhood. And then started doing prison abolition work and then somehow ended up in this space,” he said.

Madison said he plans to introduce a Wisconsin constitutional amendment to confer rights to natural lands, waters, and the environment.

“We’d be the first to acknowledge climate justice in our constitutional amendment and have the ability for environmental lawyers or anyone to sue based [on] climate change,” Madison said.

The panel concluded with speakers invited to reflect on how Harriet Tubman’s leadership and legacy connected with climate justice.

Ali said climate justice promotes equity and equality for all, especially the poor who are impacted most. “I saw [Harriet Tubman] as a pioneer, just like how we have environmental justice pioneers,” Ali said. “She was a pioneer of equity and equality.”

Tubman, known to have led at least 70 enslaved people to freedom, was said to threaten reluctant escapees with a gun if they considered turning back.

Madison said that same intensity of purpose is needed today.

“When we’re talking about climate justice, we’re talking about liberation,” he said. “Harriet was someone who fought for true liberation, but what we’re talking about right now is the liberation of the environment, the ability to thrive in a self-sustainable community. We can’t do that if we do that halfheartedly. She’s a representation of doing that wholeheartedly and understanding the risk of fighting for true justice. There is a risk in fighting for justice in all forms. And it requires sacrifice.”

Photo Gallery by Michael Timm

Story by Michael Timm, a Milwaukee Water Storyteller for the nonprofit Reflo, who did our earlier series on reintroducing the sturgeon into the Milwaukee River. He holds a 2013 master’s degree in freshwater science from UW-Milwaukee. He previously wrote and edited for the Bay View Compass newspaper.

This project is funded by the Wisconsin Department of Administration, Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration under the terms and conditions of Wisconsin Coastal Management Program Grant Agreement No. AD239125-024.21. Funded by the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office for Coastal Management under the Coastal Zone Management Act, Grant # NA22NOS4190085

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

This article is a major statement about environmental justice and a testament to what can and should be done to respond to injustice. It is very gratifying that Milwaukee has such articulate and dedicated people leading the path forward Bill Lynch