The State Supreme Court Minority’s View of Gerrymandering

226 pages of dissent that ignore key facts and data.

The first thing one notices about the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s gerrymandering decision is its sheer length—a total of 226 pages. However, most of the pages do not stem from Justice Jill Karofsky’s 48-page majority opinion, which is joined by Justices Ann Walsh Bradley, Rebecca Dallet, and Janet Protasiewicz. Instead, it comes from two of the three dissenters— Chief Justice Annette Ziegler and Justice Rebecca Bradley.

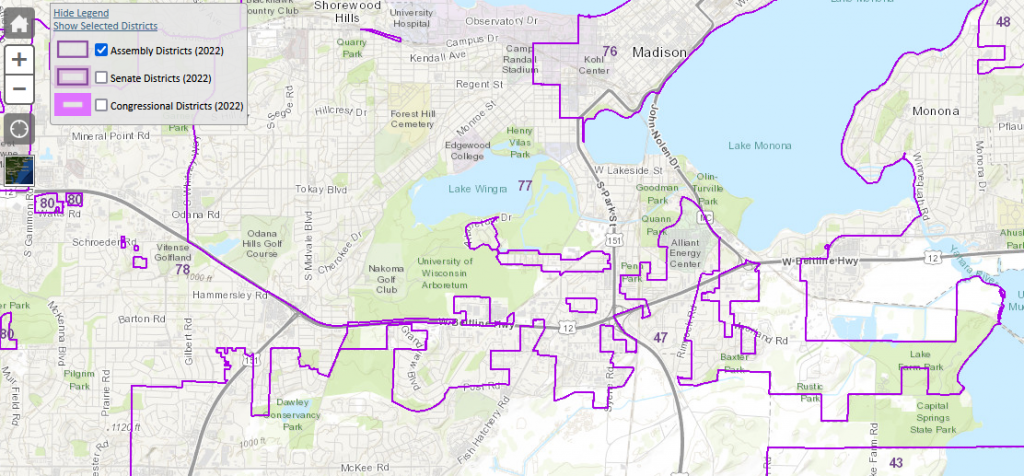

Karofsky’s opinion starts with the current district map’s violation of the Wisconsin’s requirement that districts be “contiguous.” This means that all the parts of the district are connected to the rest of the district. Instead, at least half of the districts have small “islands” that are completely surrounded by other districts. For example, see the map below of part of Assembly Districts 47 and 77 in the Madison area.

The court majority concluded that these islands do not qualify as contiguous, thus violating the Wisconsin Constitution. It offered the Legislature the chance to develop a district plan that satisfied the constitution and send it to the governor for his signature or veto.

What happens next depends on whether the governor approves the Legislature’s map. If he approves the revised maps, they take effect starting with the 2024 fall election. It is likely, I think, that his approval will not come unless he concludes the maps do not favor one or the other of the two major parties.

But the much more likely scenario is that the Legislature will submit a map to protect Republican dominance, which will be vetoed by the governor. Once again responsibility for the maps would revert to the Supreme Court. The court’s decision prepares for this eventuality by hiring two consultants, who are charged with coming up with a map that the court could select.

As I noted at the beginning of this discussion, Justices Ziegler and Rebecca Bradley offer very long dissents, in the apparent belief that more is better, that the more words one uses the more convincing the argument. More wordiness, however, often makes it harder to dig out the core of argument.

By contrast with his two colleagues, Hagedorn’s dissent is a model of conciseness, needing only 22 pages. Still, his dissent does not evince any concern about even-handedness. He starts his dissent by accusing the court majority of favoring one political party over the other:

Call it “promoting democracy” or “ending gerrymandering” if you’d like; but this is good, old-fashioned power politics. The court puts its thumb on the scale for one political party over another because four members of the court believe the policy choices made in the last redistricting law were harmful and must be undone.

Somehow he never acknowledges that the court’s aim is to remove the thumb presently on the scale. He concludes:

In a politically charged world, the judiciary should be a bulwark against the tribalism so prevalent among us. We should neutrally and consistently apply our rules of judicial process, no matter where that leads us. We should have no favored litigants or preferred outcomes.

Great sentiments, but Hagedorn has it backwards. The purportedly neutral “least-change standard” has the effect of perpetuating the gerrymander that was first passed in response to the 2010 census.

Beyond the verbiage, the dissenters’ argument goes something like this: the constitution assigns redistricting to the Legislature and the governor. The court inherited the issue only because the Legislature and the governor could not agree. Thus, the court’s role was a necessary but a limited one, to make all districts have equal populations. They then claim that least change is the most “neutral” way of doing this.

The trouble with this argument is that if one starts with a highly gerrymandered map, a least change policy results in another highly gerrymandered map. Far from being neutral, the result is highly partisan, serving to lock one party in power indefinitely. It is hard to believe that the three dissenting justices did not see this. Certainly, a least change rule could be neutral–but only if the starting maps were also neutral.

In her dissent, Rebecca Bradley complains that “the majority neglects to offer a single measure, metric, standard, or criterion by which it will gauge ‘partisan impact.’ Most convenient for the majority’s endgame, there aren’t any, lending the majority unfettered license to design remedial maps fulfilling the majority’s purely political objectives.”

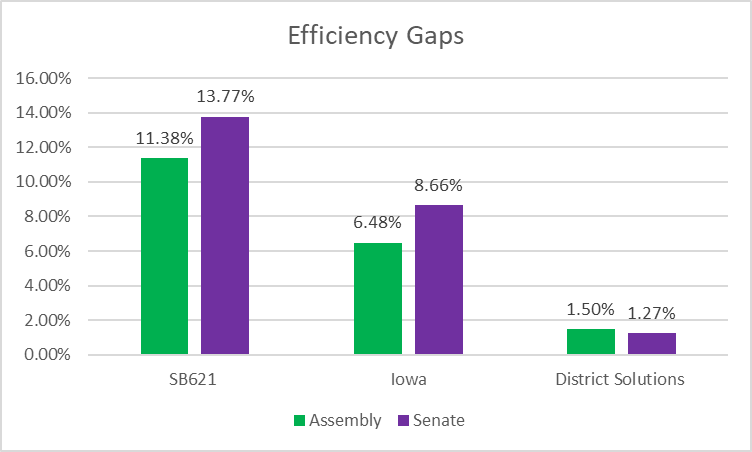

The efficiency gap is an example of one measure of partisan impact. It starts with the notion that there are two kinds of wasted votes: votes for losing candidates and votes for winning candidates that exceed the number needed to win. The efficiency gap compares the wasted votes of the two parties in an election. By custom, efficiency gaps favoring Republicans are assigned positive numbers, while those favoring Democrats are negative.

The graph below shows the efficiency gaps for six maps. The pair on the left show the efficiency gaps for the current Wisconsin maps for assembly (in green) and for senate (in purple). These gaps are very large and confirm that the Wisconsin maps are very gerrymandered.

By comparison the two columns on the right are also for Wisconsin, but for maps developed by Matt Petering of the UW-Milwaukee engineering faculty. These demonstrate what can be accomplished if the mapmakers are intent on making maps that are fair to all voters rather than favor one or the other party.

Finally, the two bars in the center show the gaps for the present Iowa maps. These show that the Iowa district maps are fairer than the present Wisconsin maps, but not nearly as fair as could be created for Wisconsin. Although Iowa is often pointed out as a model for Wisconsin, many other states have maps that rate better than Iowa’s.

Why does the Iowa model fall short? A likely culprit is a provision in the Iowa law which prohibits the use of data on voting patterns in developing the maps. This provision was also included in the Republican bill to introduce an Iowa-like law in Wisconsin, to which Democrats objected.

The Wisconsin Supreme Court’s decision on redistricting is a hopeful sign for the future of democracy in Wisconsin. That said, we are at the start of the process, not the end.

More about the Gerrymandering of Legislative Districts

- Without Gerrymander, Democrats Flip 14 Legislative Seats - Jack Kelly, Hallie Claflin and Matthew DeFour - Nov 8th, 2024

- Op Ed: Democrats Optimistic About New Voting Maps - Ruth Conniff - Feb 27th, 2024

- The State of Politics: Parties Seek New Candidates in New Districts - Steven Walters - Feb 26th, 2024

- Rep. Myers Issues Statement Regarding Fair Legislative Maps - State Rep. LaKeshia Myers - Feb 19th, 2024

- Statement on Legislative Maps Being Signed into Law - Wisconsin Assembly Speaker Robin Vos - Feb 19th, 2024

- Pocan Reacts to Newly Signed Wisconsin Legislative Maps - U.S. Rep. Mark Pocan - Feb 19th, 2024

- Evers Signs Legislative Maps Into Law, Ending Court Fight - Rich Kremer - Feb 19th, 2024

- Senator Hesselbein Statement: After More than a Decade of Political Gerrymanders, Fair Maps are Signed into Law in Wisconsin - State Senate Democratic Leader Dianne Hesselbein - Feb 19th, 2024

- Wisconsin Democrats on Enactment of New Legislative Maps - Democratic Party of Wisconsin - Feb 19th, 2024

- Governor Evers Signs New Legislative Maps to Replace Unconstitutional GOP Maps - A Better Wisconsin Together - Feb 19th, 2024

Read more about Gerrymandering of Legislative Districts here

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Amazing that the. Author does not feel it worthwhile to provide a link to the 226 page report that he is writing about. Poor journalism.

Help educate your readers instead of just lecturing to them.