Milwaukee and the Stolen Picasso

Tale from 1969 puts a city with few Picasso paintings at center of an international mystery.

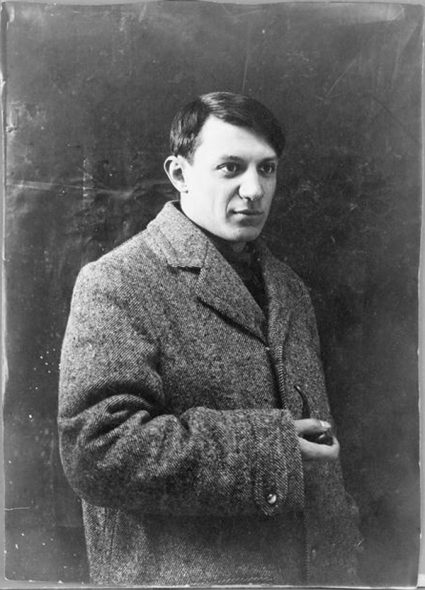

It was a Picasso painting from 1967 entitled “Portrait of a Woman and a Musketeer,” and was supposed to go to Milwaukee. It had been purchased in early 1969 by Irving Luntz, who ran the Irving Gallery, then the premier art gallery in Milwaukee. He had gotten it at a very favorable price, $40,000, from Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, a prominent dealer in Paris.

It was crated and flown oversees to Logan Airport in Boston, where the painting disappeared. The amusing tale of that inadvertent theft was told last week in a New York Times story, which skimps on Milwaukee’s role and concentrates on Merrill “Bill” Rummel, who worked for Emery Air Freight, then the country’s largest cargo airline, on the company’s loading dock at Logan airport. The painting arrived during a huge snowstorm that created chaos at the airport, with containers and boxes scattered on the tarmac and docks.

As Rummel recalled it, his supervisor told him to get rid of a crate that was missing any label. Rummel took it home, opened the crate and discovered it was a Picasso painting and though he was no fan of this style (he preferred realism) stored it in his house.

Luntz was expecting the shipment of two crates of art works he had purchased: the Picasso and an Alexander Calder mobile sculpture. The crate with the Calder arrived, but not the Picasso, and Luntz contacted authorities at Logan Airport, but they couldn’t find the other crate.

“We’ve been waiting and waiting patiently,” Luntz told WTMJ news at the time, “and ultimately we began to get a little disturbed. and as a result, we asked the FBI to get involved in it.”

The stories spooked Rummel, who, with the help of his father and brother, figured out a way to drop the painting off anonymously at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, with a cryptic note signed by “Robbin’ Hood.”

“I am absolutely delirious and delighted to get this picture back,” Luntz told TMJ.

He revealed that he had prospective buyers for the painting. Picasso “is certainly the most famous artist of our century. And this is a very fine and desirable painting,” Luntz noted. “There are more prospective buyers for an important painting than an unimportant painting.”

The buyers, it appears, were Sidney and Dorothy Kohl. At least they were listed as owners in a 1971 exhibition at the Milwaukee Art Center, the forerunner of the Milwaukee Art Museum. The exhibition was reviewed by Curtis Carter, who would later serve as the first director of Marquette University’s Haggerty Museum of Art, in a story he did for the Bugle American, an alternative weekly of the day.

Even today the museum has only one painting by Picasso, “The Cock of the Liberation, which was donated by Peg Bradley, and whose collection includes some of the most important works at the museum. (The museum also has a few Picasso works on paper.) She had originally considered donating some of her paintings to the New York Museum of Modern Art, but her husband Harry Bradley, co-founder of Allen-Bradley, told her emphatically that “we made our money in Milwaukee and our art is going to be left in Milwaukee,” according to John Gurda’s book, The Bradley Legacy.

The story, alas, is much different in the case of Sidney Kohl, who, with his brothers Herb and Allen Kohl, helped build the empire of Kohl’s grocery stores and department stores that made all three millionaires. While Herb has been a major donor to countless causes in Milwaukee, including supporting the Milwaukee Art Museum, Sidney moved to Palm Beach, Florida some 30 years ago and rarely donates to the city where he made his money. Meanwhile he has given generously to Florida organizations, with a $2.5 million gift to the Jewish Federation of Palm Beach County.

Sidney and Dorothy Kohl are also major art collectors. That may have started with the purchase of that Picasso back in 1969, when Sidney was about 40 years old. They were particularly known for collecting works by Abstract Expressionists, recalls Dean Sobel, an art professor in Colorado who served for years as a curator at the Milwaukee Art Museum.

In an interview with Urban Milwaukee Sobel recalled that former museum director Russell Bowman “was working that for years,” trying to cultivate Sidney Kohl. “As generous as Herb was to the museum, Sidney had the real treasures. It was top-shelf stuff. My memory is we never got anything.” (Urban Milwaukee contacted the Milwaukee Art Museum as to whether any works in the collection were donated by Sidney Kohl, but has not heard back.)

In 2017 Sidney and Dorothy Kohl sold eight works at auction, all abstract expressionist paintings, for just over $101 million.

As for Irving Luntz, just a few years after the Picasso incident, he moved from Milwaukee. He opened Irving Galleries in 1974 in Palm Beach, “focusing on top-quality modern master and contemporary art,” a 2017 obituary in the Palm Beach Daily News reported. “For 37 years, he reigned as one of the avenue’s canniest and most colorful businessmen, retiring in 2011.” The gallery “developed an international reputation curating the works of Picasso, Jean Dubuffet, Roy Lichtenstein, Marc Chagall, Joan Miró, Alexander Calder” and many others, as his funeral home obituary noted.

He went on to open the Michael H. Lord Gallery in Palm Beach, California. But the gallery shut down in 2013 “after Lord was evicted, sued by artists who’ve not been paid and sued over a $3.1 million debt,” as Schumacher reported.

As for the Picasso painting bought by the Kohls for an estimated $75,000 in 1969, the Times could find no record of it having been sold since. The works the couple sold in 2017 “did not include the Picasso,” the story noted, “and the Kohls did not respond to several requests to confirm that the painting — no doubt worth millions of dollars — is still in their private collection.”

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

Murphy's Law

-

The Professors Are the Enemy

![Bascom Hall on the University of Wisconsin campus. Photo by Rosina Peixoto (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://urbanmilwaukee.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Bascom_Hall_in_Madison-185x122.jpg) Jun 24th, 2025 by Bruce Murphy

Jun 24th, 2025 by Bruce Murphy

-

Can Democrats Win More Rural Voters?

Jun 18th, 2025 by Bruce Murphy

Jun 18th, 2025 by Bruce Murphy

-

Trump’s Flip-Flop on Immigrants Impacts Wisconsin

Jun 17th, 2025 by Bruce Murphy

Jun 17th, 2025 by Bruce Murphy