Powerful Art By Prison Inmates

Portrait Society presents hundreds of artworks by 65 current or former inmates. It's quite a show.

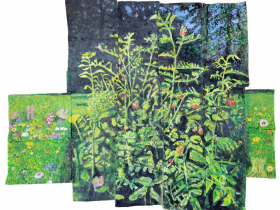

M. Winston, Shorewood, 2020, acrylic on paper. Photo by Daniel McCullough.

The United States has the highest incarceration rate of any country in the world. Currently, there are 2.3 million individuals in the nation’s criminal justice system.

This fact hovers over a remarkable project that has unfolded into an expansive declaration of visibility, of resilience and of healing. “Art Against the Odds” is the first museum-scaled exhibition of artwork created by currently or formerly incarcerated people in Wisconsin.

The paintings, by incarcerated artist M. Winston, are the deeply imagined places of a mind searching for solace. Winston, who will soon complete a 30-year sentence, has been able to maintain hope and an “interior sense of beauty” by creating these artworks. To the artist, they are a vehicle for redemption.

Winston’s experience and his expansive creative output led Brehmer, along with her gallery manager and co-curator Paul Salsieder, to consider how art created in prison could stand as a testimonial to lives lived out of the public eye, to give a voice and a humanity to people deemed unworthy of this.

Shannon Ross, who was formerly incarcerated and who now holds a graduate degree in Sustainable Peacebuilding at UW-Milwaukee, founded a newsletter, The Community, as a way to keep “system impacted populations abreast of their rights.” Brehmer and Salsieder put a notice in the publication describing the project. Inmates inundated the gallery with letters and artwork. All told, the exhibition includes the artwork of 65 artists, and consists of hundreds of objects. The exhibition also documents some of the hundreds of handwritten letters exchanged with inmates during the two years of exhibition development.

Brehmer has long understood that the art world exists far beyond the white cube of her gallery’s walls. She has mounted exhibitions around protest movements and sought artists that do not comfortably fit into the conventional canons of contemporary art. She also began a project, On The Wing, (which receives non-profit status through a fiscal receiver), to offer sketchbooks and supplies to underrepresented groups in Milwaukee through the House of Peace. This philanthropic project was used as a catalyst to begin building and funding “Art Against the Odds.”

Nearly 100 individual donors and foundations contributed to the project. Framing the artworks for the exhibition alone cost $30,000.00. Brehmer explains that elevating the artwork into a museum quality exhibition was vital, as she did not want to create a separate, isolated category for this work, which should be considered in context with the contemporary art world.

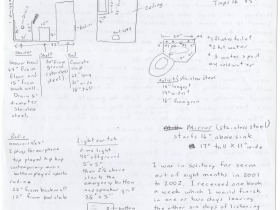

The exhibition takes care to offer viewers context around the artworks and also carves out spaces that relate to the prison experience itself. Artist Dominic Marak created a minutely detailed drawing of his solitary confinement cell, complete with the dimensions and materials that comprise the floor drain, the toilet, the light switch. The exhibition displays a room created from the artist’s measurements that guests can enter. Marak literally spent months at a time in solitary confinement, an experience described as torture by Jessica Wolfendale in her essay in the exhibition catalog. Wolfendale is a professor of philosophy at Case Western University and author of the book “Torture and the Military Profession.”

In spite of this, Marak created many objects in the show, including collaged conceptual portraits of friends, traditional pencil portraiture, as well as a series of painted American flags titled “Thou Shalt Not Kill,” on which are inscribed in a carefully scripted cursive the names of individuals executed by capital punishment. Marak died in prison before the exhibition opened.

One of the few female artists in the show reflects on her time in prison by looking in the mirror. Since her release six years ago, Sarah Demerath has painted abstracted eyes, painted as remembrances of how her eyes appeared to her in various stages of a years-long addiction to heroin. The images are colorful, and though beautiful, remain deeply haunting.

Other artists like M. Winston spent time looking beyond their prison experience to imagined and remembered places. To many incarcerated individuals, the magic and calm of the late artist and TV personality Bob Ross remains a palliative. Incarcerated artist Sean Riker describes a suicidal episode in prison. Discovering Ross’ show “The Joy of Painting” literally saved his life. Though Riker’s colorful landscapes echo Ross’ fictive scenes to a certain degree, Riker’s isolated cabins in the woods bear a darker psychology. There is always a lighted window and a dark path leading to these lonely houses. A deeper narrative lurks behind these scenes.

This type of poetic reflection, the memory and imagination of more beautiful places, and intricate descriptions of pain and longing, coalesce in this exhibition to offer a deep insight into the experiences of the incarcerated population in our country. However, these works do not deny that pain has been inflicted by crime, and the exhibition honors the victims and survivors. But as with all people, the artists in this exhibition are far more than simply the crimes they are defined by. Their art has created a healing and a redemptive voice that has risen far beyond the physical walls of their prison.

“Art Against the Odds,” at the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design, will be exhibited through March 11.

“Art Against the Odds” Gallery

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.