Politics and Population Density

It's remarkable: The further voters live from the center of Milwaukee the more Republican their views.

Gov. Tony Evers speaks to reporters following the primary election Wednesday, Aug. 10, 2022, in Madison, Wis. Angela Major/WPR

There has been considerable attention recently to the increasing alignment between population density in the United States and partisan election voting. Cities, such as Madison and Milwaukee have increasingly voted for Democratic candidates, while small towns and rural areas in Wisconsin have become increasingly supportive of Republicans.

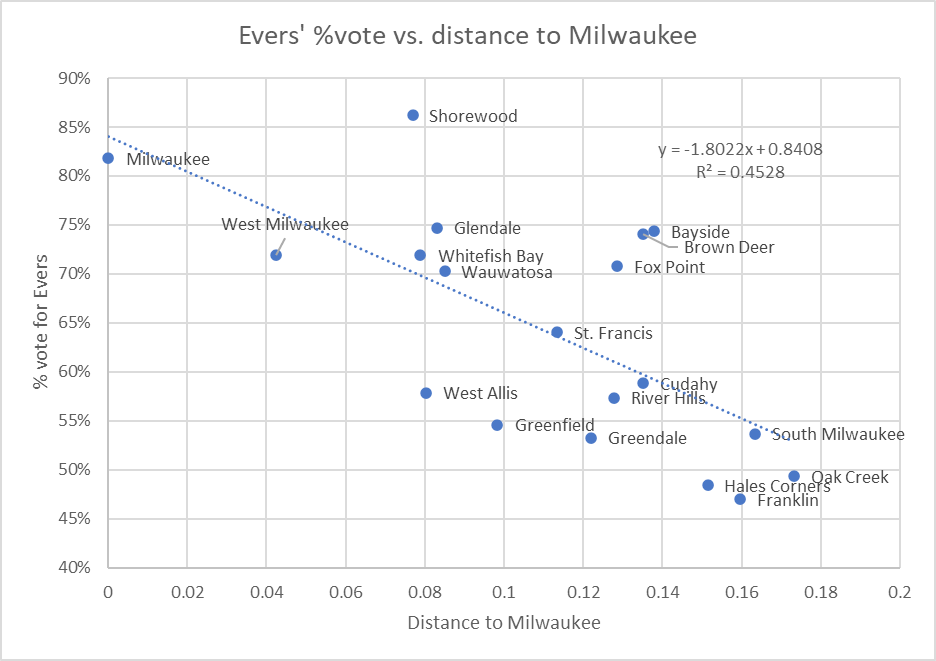

The chart below compares the relationship between the percentage of the vote that went to Tony Evers in Milwaukee County municipalities and the approximate distance between Milwaukee and each suburb. R2, the coefficient of determination, is often described as showing how much of the variability of one factor can be caused by its relationship to another related factor. In other words, in Milwaukee County, about 45% of the variation of the partisan vote reflects the distance from Milwaukee.

Evers’ % vote vs. distance to Milwaukee

Note that in all these cases, I only include votes for the two major-party candidates: Tony Evers and Tim Michels. Thus, one can calculate the Michels vote by subtracting the Evers percentage from 100%.

As can be seen from the plot, Milwaukee ranked second for the percentage of its voters supporting Evers. Shorewood had the highest proportion. This may be consistent with the model. Because Milwaukee covers so much territory, many Milwaukee voters will be further from central Milwaukee than the Shorewood voters.

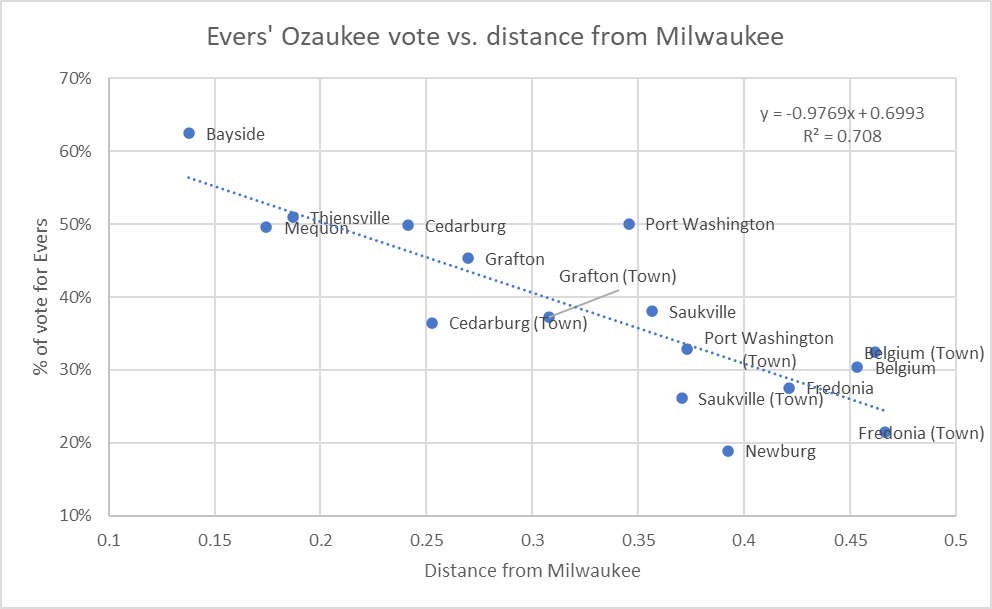

The next graph shows the results of the same analysis when applied to Ozaukee election results. Here, the relationship is even stronger than for Milwaukee County, with an R2 above 70%.

Ozaukee County was not Evers Country. His only comfortable win was in the small portion of Bayside located in Ozaukee County, which is separated from the rest of Ozaukee County by a ravine, meaning one must go through Milwaukee County to access that part of Bayside.

The next closest municipalities, Thiensville and Mequon, were ones that Evers barely won or barely lost. Two others where the vote was very close, Cedarburg and Port Washington, are the kinds of places likely to attract Democrats.

Evers’ Ozaukee vote vs. distance from Milwaukee

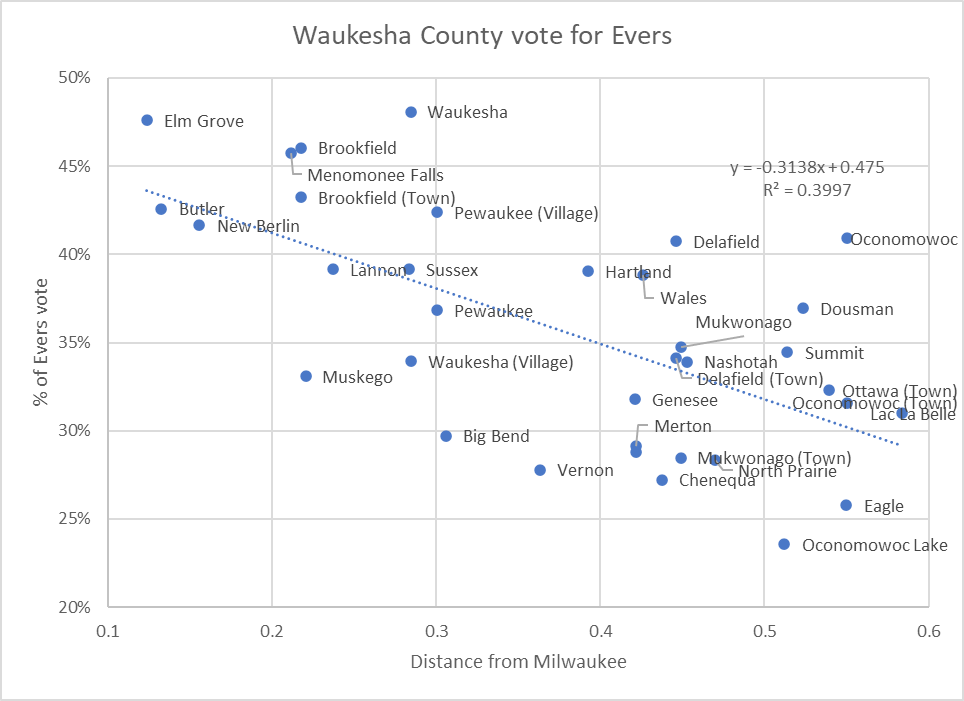

Finally, the next graph applies the same analysis to Waukesha County. While weaker than in Ozaukee County, the same pattern appears, with an R2 of around 40%. Evers won no Waukesha County municipality, but–think Elm Grove–several were close.

Evers did considerably better in the city of Waukesha than would be predicted by using only its distance from Milwaukee. But the city of Waukesha presents a special case, as it is itself something of an urban environment.

Waukesha County vote for Evers

Within the Milwaukee metropolitan area, there is a pattern that repeats itself again and again: the further away a community is from Milwaukee it is, the more Republican it votes. By the same token, the closer it is the more Democratic it votes. This pattern repeats throughout the data.

But what accounts for this pattern? Are Democrats attracted to more urban neighborhoods and Republicans to more rural and suburban ones?

Is there some signal that counties give off that attracts people sympathetic to one party while repelling those in the other party? Something that says, “you will be comfortable (or not) here”?

I don’t want to overstate the issue. A healthy minority of Democratic voters live in Ozaukee County, for instance—about 23,000 or 44.5% compared to almost 29,000 Republican voters. So, whatever it is that made the county attractive to more Republican voters stopped well short of making the county uniformly Republican.

That the phenomenon is real is supported by the evidence. The cause, however, is a mystery.

Note on the distance calculations: In calculating the distances between Milwaukee and other towns, villages and cities, I started with a function in Excel which generates data for geographic entities, including Wisconsin’s municipalities. Among the data generated are the latitude (how far north or south the entity is) and longitude (how far east or west of Greenwich England it is). I then took the differences of the latitudes and longitudes, squared the differences, added up the squares, and took the square roots or the differences, which I used as the distances between municipalities.

Sticklers for accuracy may note that this calculation ignores the earth’s curvature. The further away from the equator the closer together the north-south lines are. As a result, a given difference in longitude will shrink as we go north. For simplicity I chose to ignore this effect.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

Data Wonk

-

Why Absentee Ballot Drop Boxes Are Now Legal

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Imperial Legislature Is Shot Down

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

Counting the Lies By Trump

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

This is a fascinating analysis. I’d like to offer a preliminary possible hypothesis: dense living both requires and gives rewards for people who seek common ground and the common good; the economies of scale for infrastructure and amenities mean that outsize benefits can be gained through cooperation; public infrastructure from parks to transit to libraries and schools (and more) can be built through cooperative efforts. The resulting density has been shown to correlate with economic productivity, and so the advantage of a central location rewards participants and can draw more people seeking opportunities. Cultural and population trends have supported the advantage of cities–despite all kinds of setbacks for cities (pandemics, fires, suburbanization, globalization, new economies)–for at least the past 20,000 years. The success of this dense living requires not just tolerance and acceptance of diversity but a celebration of it. This is explanatory of why Wisconsin Republicans dislike the cities and expend effort to weaken and harm them. Cities are powerful products of civilizations, but they are complex and diverse and have unique challenges specific to denser living. False dichotomies or accusations of socialism or other absurd political rhetoric have fostered harm to cities. The tragedy is that this diversity of both density and political viewpoint is both natural and advantageous for a state big enough for all views and lifestyles. People who think the state is or should only be rural or only urban are mistaken–there exists a vast range of political and cultural geography, all with unique opportunities and challenges. Political polarization that seeks to drive out a vast spectrum of options for living and lifestyle in all forms leads to a stalemate and a loss of human potential. At a higher level, cooperation must be required among these disparate viewpoints to allow that diversity to flourish (sometimes this is called “representative government”). I am concerned that the Republican legislature in Wisconsin is so concerned in the face of the power of cities that they are doing anything they can to weaken them, including through gerrymandering, and to destroy representative government. Again, this is too bad, as it harms the economy and opportunities the state could offer. Instead of calls for political dominance, we should be celebrating and finding ways for diversity to coexist–Vive la différence!