Can Ranked Choice Voting Calm Political Rancor, Extremism?

The voting system would also solve the third party problem in the American political system.

![Sarah Palin. Photo by Gage Skidmore [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://urbanmilwaukee.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Sarah_Palin_by_Gage_Skidmore_2-horizontal.jpg)

Sarah Palin. Photo by Gage Skidmore [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

To understand ranked choice voting, it is useful to compare it to the most common model for deciding who won an election in the United States.

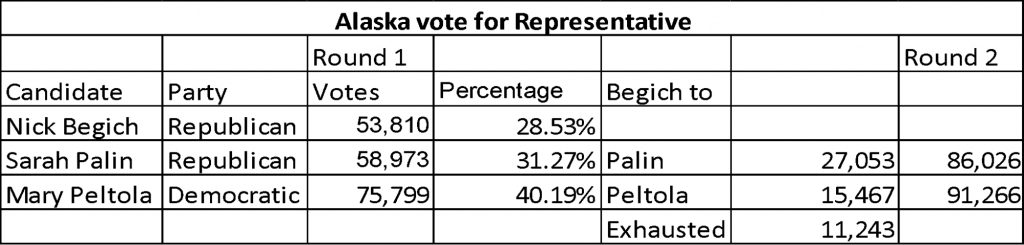

In ranked-choice voting, voters are asked to rank the candidates: 1st choice, 2nd choice, etc. Alaska recently implemented ranked-choice voting. The table below summarizes the recent election to fill out the term of Alaska’s delegate in the United States House of Representatives.

Three people competed in this election (a fourth dropped out): Republicans Nick Begich and Sarah Palin, and Democrat Mary Peltola. Of the three, Begich received the smallest number of votes (53,810).

Under the ranked-choice system, 27,053 of his votes were distributed to Palin and 15,467 to Peltola, based on Begich voters’ second choices. Perhaps surprising, 11,243 Begich voters did not make a second choice.

Adding the Palin second choice votes to her original vote total gave her 86,026 votes to Peltola’s 91,266. Thus, Peltola became the first Democratic Representative from Alaska in fifty years.

Ranked-choice voting skeptics may note that the result would be the same under the old system: Peltola would have won because she had the most votes. However, I think that the process gives her a certain credibility: rather than a fluke result due to Republicans splitting their votes between two candidates, she can credibly claim support from the majority of voters. Or as a New York Times article on the Alaska special election notes, the result may simply reflect that Peltola has a reputation as a very nice person.

In any case, the special election that she won only allows her to fill out the remainder of Representative Don Young’s term. Come November, the same three people will compete to win a full two-year term. Perhaps that will offer more evidence as to whether ranked-choice voting offers better democracy.

Ten Republican members of the U.S. House of Representatives voted to impeach then-President Trump following the January 2021 riot at the US Capitol. This action made them targets for Trump and his supporters. Of the ten, four decided to retire rather than run for another term. Three of the others were defeated in their districts’ Republican primaries.

The tenth member of the group voting to impeach Trump also participated in Washington’s ranked-choice voting. She lost to the Trump-endorsed candidate, but only narrowly. The vote was 22.8% to 22.3%.

One of the candidates who lost in the Republican primary was Peter Meijer, who was also a victim of a Democratic strategy of promoting MAGA Republican candidates in the expectation that they would be easier to defeat in November. With the help of ads from the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, Meijer lost to Trump-backed John Gibbs by a vote of 48.3% to 51.7%. (I share the belief that the Democratic committee’s strategy was dangerous, unpatriotic, and unethical.)

Evidence from the most recent round of primary elections gives added evidence for the hypothesis that ranked-choice voting tends to reflect the whole of their constituency, rather than one or the other wings of it. By contrast, the present model, in which candidates must survive a partisan primary system whose bias is towards one or the other of the extremes.

In the past legislative session, bills have been introduced that would have moved Wisconsin in the direction of ranked-choice voting at least for some elections. Perhaps the most serious effort was Senate Bill 250 and Assembly Bill 244. The twin bills were introduced in their respective houses in March of last year. Their sponsors were a bipartisan group of legislators, but more Democrats than Republicans. It had a hearing in the Senate but none in the Assembly. With the end of the current session, both bills died.

A second pair of bills, SB 240 and AB 150, would have included elections for state offices. In this case, all the sponsors were Democrats. Considering how gerrymandered Wisconsin is, without the participation of Republicans, it is not surprising that this bill gathered little attention.

Ranked-choice voting has both its supporters and critics. Unlike other public issues, supporters and critics do not neatly line up according to their place on the partisan spectrum. For example, an article in the Federalist, a conservative online publication, claims that a proposed ranked-choice ballot amendment to the Nevada constitution is opposed by that state’s Democratic governor and two U.S. Senators.

One likely effect of ranked-choice voting is delaying the reporting of voting results. In the Alaska case described at the start of this article, the election result could have easily flipped if more Begich voters had marked Palin as their second choice.

On the other side, it is clear that ranked-choice voting completely eliminates the third-party quandary, the fear that voting for a third party increases the odds that the voter’s most disliked major party candidate will win.

More broadly, it seems logical that ranked-choice voting shifts power from the extremes to the middle. It also seems logical that some candidates may think twice about launching a vicious attack on a rival if they hope to become the second choice of that rival’s supporters.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson