State Supreme Court Rules in Milwaukee ShotSpotter Case

Court says gunfire detection met standard for reasonable suspicion in man's arrest.

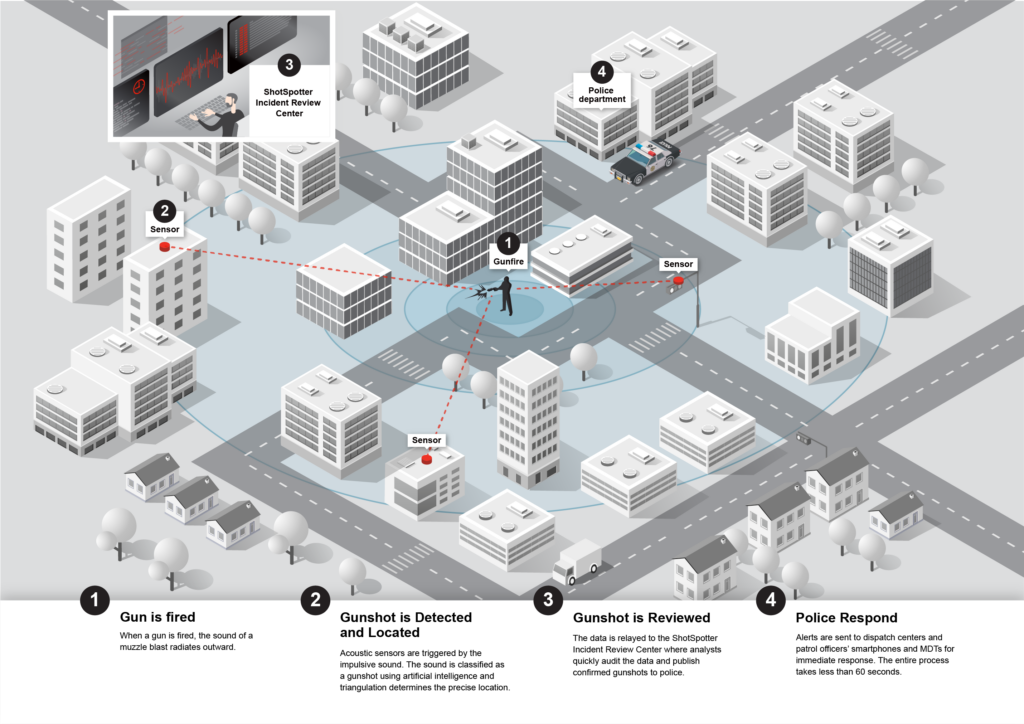

The Wisconsin Supreme Court has rejected motions to suppress evidence in the 2019 arrest of a Milwaukee man. Avan Rondell Nimmer was arrested after Milwaukee Police Department (MPD) officers responded to a ShotSpotter alert. ShotSpotter is a network of acoustic sensors deployed across four MPD districts that triangulates the location of loud impulsive sounds identified by analysts to be gunshots. Responding within a minute of the alert, officers stated they saw Nimmer walking alone on the sidewalk. Nimmer allegedly quickened his pace as he dug around in his left pocket, shielding that side from the officers’ view. Finding those actions suspicious, the officers proceeded to pat down Nimmer, who admitted he had a gun in his waistband. Nimmer was arrested for being a felon in possession of a firearm.

The case raised novel questions about ShotSpotter’s reliability and implications for Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable search and seizure by the state. Milwaukee Circuit Court Judge Glenn Yamahiro convicted Nimmer, who pleaded guilty. But he appealed on the grounds that the search had violated his rights and the evidence should have been suppressed. The Appeals Court agreed, reversing the conviction, and Nimmer’s case went to the Wisconsin Supreme Court.

Last year, Milwaukee’s ShotSpotter system was activated 21,479 times, or nearly 60 times a day on average. Not all of those “hits,” however, were actually verified gunshots. The city’s system is managed by its fusion center, one of Wisconsin’s two law enforcement intelligence hubs. The fusion center also operates pole cameras, which it can use in tandem with ShotSpotter alerts to view a potential scene before officers arrive. In Nimmer’s case, however, according to the Supreme Court’s decision filed on Thursday, officers had an alert of four confirmed gunshots and a location through the ShotSpotter. They did not, however, have a description of a suspect.

Justice Rebecca Dallet questioned aspects of the arrest while also concurring with the majority opinion that upheld Nimmer’s conviction. Dallet noted that Nimmer was arrested at 10:06 p.m. on a Saturday evening and claimed he was out for a walk at the time. Officers reached the location about a minute after receiving the alert. Dallet acknowledged the seriousness of potential gunfire in a residential neighborhood. “But the possibility that a crime has been committed in a certain neighborhood doesn’t cast suspicion over everyone there,” she wrote. “Moreover, there is nothing especially suspicious about finding someone alone on a residential street just after 10:00 P.M. on a Saturday night in the summertime.”

Dallet also referred to studies that raised questions about ShotSpotter’s accuracy. One review of Chicago’s use of ShotSpotter found that in over 90% of cases where officers responded to an alert, no gun evidence was located. The accuracy of ShotSpotter is a hotly debated topic, with privacy activists questioning whether it helps reduce crime and the ShotSpotter company boasting decreases in homicides and violent crime for many of its customers. It also points to studies that show most gunshot incidents go unreported to 911. A national campaign #CancelShotSpotter has pushed back against many of the company’s claims.

“This is not a trivial issue,” argued Dallet. “No matter how accurate ShotSpotter is or how quickly officers respond to a ShotSpotter alert, it cannot be used as a dragnet to justify warrantless searches of everyone the police find near a recently reported gunshot.” Dallet added that “at best, ShotSpotter gives officers only a reason to go to a particular place, but it’s what they find there that is most relevant to the analysis of whether they had particularized, reasonable suspicion.”

Bradley rejected many of the arguments made by Dallet, calling them “straw man” arguments. She accused Dallet of “attempts to distort the holding in this case” by suggesting the court sanctions ShotSpotter’s use as a warrantless dragnet. “Nothing in this opinion suggests anything of the kind,” Bradley wrote. “As exhaustively explained, the totality of the circumstances obviously matters and it is the totality of the facts in this case which supports reasonable suspicion.”

Bradley writes that Dallet “fails to acknowledge the seriousness of gunfire in a residential area, asserting this court’s ‘analysis places too much weight on some of these facts, including the residential setting’ and ‘puts too much emphasis on the officers’ reliance on ShotSpotter.” Bradley added, “a shooter is not entitled to ‘one free shot.’’”

Dallet expressed the fear that the majority opinion will be interpreted too broadly by lower courts. “I also worry that the majority/lead opinion over-complicates its analysis by importing Fourth Amendment principles from other contexts, even though this case requires only a straightforward application of Terry,” Dallet wrote, referencing the Terry Stop doctrine that allows the police to briefly detain a person based on reasonable suspicion of involvement in criminal activity.

While concurring with the lead decision, Justice Brian Hagedorn expressed his own concern that “portions of the court’s opinion go farther than necessary. In particular, the opinion suggests — for what appears to be the first time in the Wisconsin reports — that the quantum of suspicion necessary to conduct an investigatory stop is lower for the type of criminal investigation that occurred here.” That particular issue, he wrote, was not sufficiently developed for him to have an opinion, and “resolving it is unnecessary to decide this case.”

Supreme Court rules in Milwaukee case involving ShotSpotter was originally published by the Wisconsin Examiner.