National Campaign Challenges Gunfire Detection Tech

#CancelShotSpotter questions effectiveness of the technology, highlights public privacy concerns.

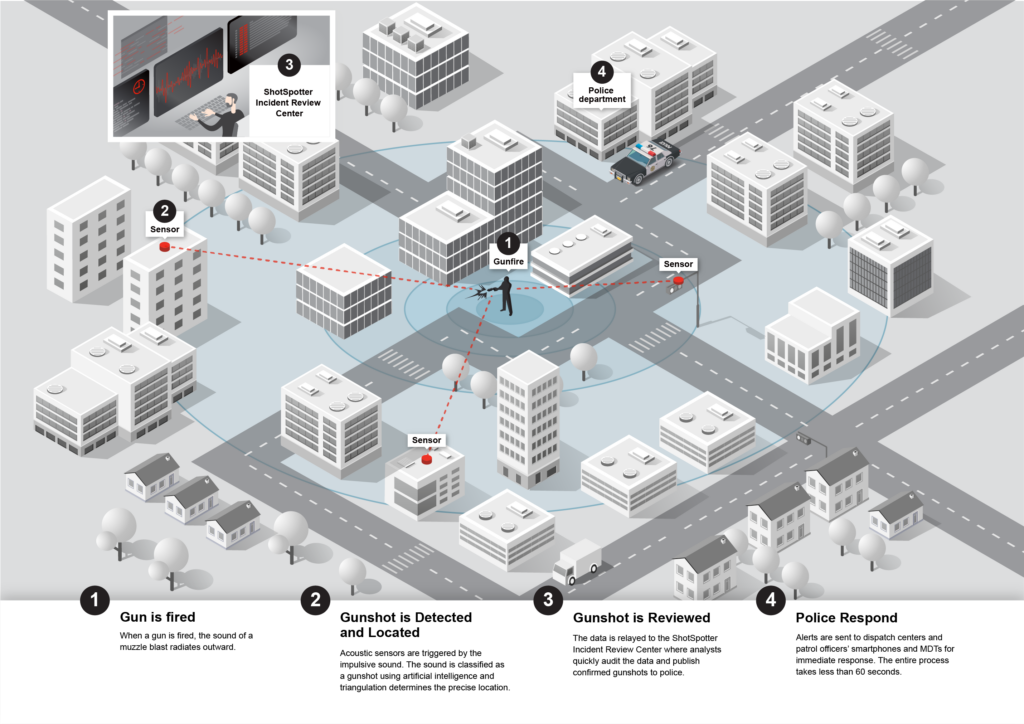

A diagram showing how ShotSpotter works. (Screenshot courtesy of ShotSpotter)

In cities around the country, through networks of audio sensors scattered in a neighborhood, loud sounds like gunfire can be detected and their source triangulated. Called ShotSpotter, the system operates in 125 U.S. cities, including Milwaukee. Police departments and the ShotSpotter company say the system offers real-time intelligence on when and where a gunshot occurs.

Now concerns over privacy and questions about the technology’s effectiveness have fueled a movement opposing the use of ShotSpotter.

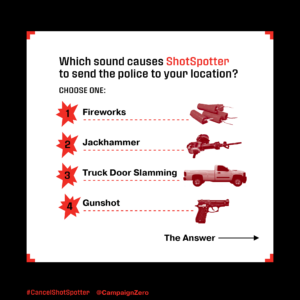

The Milwaukee Police Department (MPD) is ShotSpotter’s only Badger State customer, having adopted the technology in 2010. Last year, the ShotSpotter system was activated 21,479 times — nearly 60 times a day on average. Not all of those activations were necessarily gunshots, however. The sensors, deployed atop tall buildings or utility poles, will pick up any loud, impulsive pops, booms, and bangs — such as gunfire, but also things like cars backfiring, fireworks or other sources.

When police respond to a scene where ShotSpotter has purportedly detected gunfire, said Jacob Wourms, campaign and research manager for Campaign Zero, “they rarely find the shooter, they rarely find the perpetrator.” Instead, Wourms told Wisconsin Examiner, “The people that police are interacting with are just people in their neighborhoods going about their day, who just happen to be at the location of an alert minutes after the fact.” Police in those situations may treat community residents as suspects. He calls ShotSpotter “a reactionary tool, not a preventive tool. A lot of city councils adopt this thinking that they’re going to prevent gunfire, or do something about the gunfire. This is not what this is.”

ShotSpotter. (Courtesy of #CancelShotSpotter and Campaign Zero)

Ron Teachman, director of public safety solutions at ShotSpotter, told Wisconsin Examiner that the systems are designed to screen out the noises that aren’t from firearms. “Once captured, ShotSpotter’s computers dismiss sounds that are clearly not gunfire such as fireworks or helicopters,” Teachman said. “The remaining sounds are immediately sent and reviewed by highly trained acoustic experts.” Those technicians replay the recorded sound and inspect the audio waveform it produces. Their goal is “to see if they match the typical pattern of gunfire, assess the grouping sensors that participated, and either publish the incident to the police as gunfire, or dismiss as a non-gunfire event. This entire process typically occurs within 60 seconds from the time of the gunfire to the time the alert is sent to law enforcement.”

Milwaukee’s ShotSpotter system is part of the city’s Fusion center, the police department’s intelligence hub. Fusion performs numerous functions in partnership with local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies. It uses the ShotSpotter system in tandem with other technologies, such as the city’s pole cameras. Fusion center personnel can remotely access city cameras near the site of a ShotSpotter alert and quickly view the surrounding area. Since the nearest squad car could be several minutes away stuck in traffic, the remote access offers a second option. Some cameras, the use of which are also expanding in the city, are also equipped with license plate reader technology.

Three years after Milwaukee adopted ShotSpotter, the Fusion center came under the command of MPD Captain David Salazar in 2013. At that point, the ShotSpotter system was expanded, according to Salazar’s biography. Salazar now serves at MPD District 2, where he’s been assigned since 2020. MPD told Wisconsin Examiner that the system has not been expanded in more recent years.

ShotSpotter requires an investment from cities; with the cost depending on the size of the area to be covered. “On average, ShotSpotter costs $70,000 per square mile per year, which breaks down to about $7.99 per square mile per hour of coverage,” Teachman said.

Today, ShotSpotters are distributed across MPD Districts 2, 3, 5 and 7 — districts that encompass much of Milwaukee’s predominately African American North Side and largely Latino areas of the South Side; some include neighborhoods where homicides and gun violence are concentrated.

The ShotSpotter website includes claims that the technology has improved public safety operations. The company credits the system with a purported 53% decline in homicides in Hot Springs, Arkansas, a 26% reduction in violent crime in Las Vegas, Nevada, a 29% decline in gun violence injuries in Greenville, North Carolina, and a 55% decrease in homicides in Omaha, Nebraska in 2019. In Milwaukee, ShotSpotter played a role in the arrest of a man who was allegedly involved in an officer-involved shooting. The man, Jamel Barnes, was sentenced to 10 years in prison and an additional 11 years of extended supervision.

In February, TMJ4 reported that ShotSpotter sensors had been deployed in areas with the highest African American residents, despite having fewer alerts than another more diverse district. The report found that District 5, which had the highest number of officers drawing their guns on citizens, averaged about seven minutes and 23 seconds from getting a ShotSpotter alert to responding on-scene. For Districts 3 and 7, the average was nine minutes and 13 seconds, and nine minutes and eleven seconds, respectively. District 5 officers drew guns on citizens more often than any other between December 2020 and August 2021. That district was also the subject of controversies over a recent in-custody death which led to a retaliatory shooting in the district’s lobby.

To make the case for the need for ShotSpotter, Teachman pointed to a study by the Brookings Institute that found that just 12% of gunfire incidents result in a 911 call to report gunshots. The study also found that just 2% to 7% of incidents result in a reported assault with a dangerous weapon. Teachman stated a lack of people reporting gunshot incidents fuels the cycle of violence . “This means gunshot wound victims may not receive life-saving help, gun crime cases go unsolved, and law enforcement’s inability to respond to crimes can lead to normalized violence and community distrust,” he said.

On its CancelSpoptShotter website, Campaign Zero, challenges some of those findings. “The Brookings Institution study did not validate ShotSpotter’s ability to differentiate between loud noises,” the organization states. “Instead, it used ShotSpotter’s self-reported alert numbers to compare against 911 calls for service.” A 2021 study by the MacArthur Justice Center on ShotSpotter usage in Chicago also found more than 40,000 alerts where evidence of gunfire or a gun-related crime were absent.

Since ShotSpotter arrived in Milwaukee in 2010, homicides and gun violence in the city has risen and fallen. After peaking in 2015, Homicides began to fall in Milwaukee until 2020 when the numbers skyrocketed. Many things appear to correlate with that timeline, including the number of concealed carry licenses issued year to year, and community organizing around violence prevention strategies.

A graphic of the different kinds of sounds that can cause a ShotSpotter alert. (Photo courtesy of CancelShotSpotter and Campaign Zero.)

DeRay Mckesson, executive director for Campaign Zero, questions the reliability of some of the statistics. “Show me Milwaukee, show me Denver, show me all the city’s they’ve looked at,” said Mckesson. “When we ask the question of, ‘okay you had it [ShotSpotter]. Has crime decreased in the area, yes or no? And if it’s decreased, what’s the relationship between that decrease and ShotSpotter? You would think we were asking the world’s toughest question and we’re not.”

Mckesson and Wourms also question whether ShotSpotter has led to measurable impacts on the police department’s ability to solve shootings. According to data from MPD, the causes of a large portion of both fatal and non-fatal shootings from 2019-2021 were listed as “unknown.” During 2019, the city saw 79 firearm-related homicides: 24 were listed as arguments or fights, 21 as “unknown,” 10 due to domestic violence, nine due to drug-related activity, six for retaliation, with other categories getting lower numbers. The cause or context was listed as “unknown” for the majority of firearm-related homicides for 2020 and 2021. For non-fatal shootings, the numbers were similar.

In a statement to Wisconsin Examiner, the MPD said there wasn’t data available for it to determine whether the department’s clearance rate has improved since ShotSpotter was instituted 12 years ago. The department was also unable to determine whether the system has had a positive or negative effect on response time. “There is no data available to answer this question,” the department stated, “however, we are immediately alerted by the system and officers may respond faster to an incident where a firearm was discharged.”

In addition to questioning the system’s effectiveness, critics also warn of privacy concerns. In some parts of the country, ShotSpotter alerts that contain voice audio shortly after shootings have been admitted in court as evidence.

A 2019 study published in the Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery concluded that, “the activation of the ShotSpotter technology increased the likelihood of police transport of gunshot victims. Furthermore, the use of this technology resulted in shorter response times as well as transport times for both police and EMS. This technology may be beneficial in enhancing the care of victims of penetrating trauma.” MPD has also used the system to distill the collected data into larger analysis’ within the Fusion center.

Mike Katz-Lacabe, director of research at the Center for Human Rights and Privacy, highlighted this concern. “Once ShotSpotter has these microphones deployed, does anything prevent them from using the sounds picked up by the microphones for other purposes?” Katz-Lacabe asked in an interview with Wisconsin Examiner. “For example, if the microphone picked up the sound of someone screaming, an argument, glass breaking, etc. Why couldn’t they create alerts for those sounds as well?”

Teachman said that ShotSpotter takes such concerns seriously. “ShotSpotter takes privacy very seriously and has structured its technology, processes, and policies in such a way to minimize risk of privacy infringements while still delivering important public safety benefits,” he said. “ShotSpotter sensors are designed to activate only when loud, impulsive sounds—pops, booms, and bangs—are heard.”

Teachman added: “The risk of human voice surveillance is extremely low as determined by an independent audit conducted by the New York University Policing Project. There is no direct access to extended audio pre-and post-incident. Audio of the incident is limited to short ‘snippets’ that are transmitted to reviewers at ShotSpotter’s Incident Review Centers. These snippets include only a few seconds of gunfire and one second before and after to establish an ambient noise level. Any sounds picked up by ShotSpotter sensors are stored for only 30 hours and then overwritten.”

Milwaukee Police echoed that perspective. “My understanding is we don’t gather voice audio,” Sergeant Efrain Cornejo of MPD’s press office told Wisconsin Examiner. “However, when there’s an activation, for example, when there’s shots being fired and it gets recorded, occasionally you will be able to hear, maybe, someone screaming or something during that short period that it records. But we just don’t do anything with that audio. But it is a possibility that the microphones can catch someone speaking.”

Katz-Lacabe, who’s a veteran watchdog of the Oakland commission, offered a different interpretation of the city’s decision to keep ShotSpotter. “Oakland PD a few years back wanted to get rid of ShotSpotter because it wasn’t an effective way of allocating scarce resources,” said Katz-Lacabe. “They were overruled by the City Council, who wanted to keep it because it made them look like they were doing something to improve public safety.”

In 2019, the Privacy Advisory Commission of the City of Oakland unanimously approved the Oakland Police Department’s continued use of ShotSpotter, Teachman said, despite the commission boasting strong ordinances geared specifically towards local police surveillance.

Katz-Lacabe attributes the appeal of ShotSpotter to the appearance of being proactive. “Police departments like ShotSpotter because it results in lots of alerts and if the police can’t respond to all of them in a timely fashion, they have a good argument for hiring more officers or paying overtime to existing officers,” he argued. “City council members like ShotSpotter because it makes them look like they’re doing something to improve public safety and they almost never go back to review data to see if it had any beneficial impact on public safety.”

For Teachman, the continuation of ShotSpotter programs in 125 cities is a sign of its success. “Like any business, we turn to our customers to ultimately determine the value and sanctification with our products,” said the ShotSpotter executive . “We are trusted by police departments in over 125 cities nationwide and have a 98% customer retention rate, indicating that our system works well.”

Katz-Lacabe said that the effect the sensors have on community interactions with police can’t be ignored. “It does seem to encourage police arriving at a ShotSpotter alert location amped up and with guns drawn, ready for someone with a gun,” he said. “This can be quite dangerous for those in the community, which is typically populated by lower-income and minority populations. And that’s because that is where ShotSpotter microphones are situated.”

The CancelShotSpotter campaign highlights many of those concerns, and has grown since launching a month ago. “In terms of the product as a whole, we just started with a hunch,” said Wourms. “We were like, this doesn’t sit very good.”

Beyond questions about the reliability of the data and its effects on community interactions, the campaign’s organizers are concerned about transparency. “Cities are under the impression that they own the data once they sign a contract with ShotSpotter, that’s not true,” said Wourms. “ShotSpotter takes ownership of the data and only provides it to the city as long as the contract stays active. So ShotSpotter itself has an enormous amount of power to assist in blocking public records requests, which we have a serious issue with because it’s paid for with public tax dollars.”

Wourms highlighted a 2015 ShotSpotter document which outlined for police departments how to either deny an open records request for ShotSpotter information, or provide a limited data set. Such confidentiality is commonplace among surveillance technologies utilized by law enforcement.

Katz-Lacabe says ShotSpotter shares the flaws of other similar technologies. “The idea behind ShotSpotter, license plate readers, and surveillance cameras is that if police can monitor enough things, they will be able to arrest all the people responsible for committing crimes,” he told Wisconsin Examiner. “It’s also a great way to control people, if they can be led to believe that all of their actions are being monitored when they’re in public.”

National campaign puts its sights on popular police gunfire detection tool was originally published by the Wisconsin Examiner.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.