The Lady Murderer of Milwaukee

Anna Louise Sullivan poisoned her husband, stepson and others and was very jolly about it. Excerpt from ‘Historic Milwaukee Crimes.’

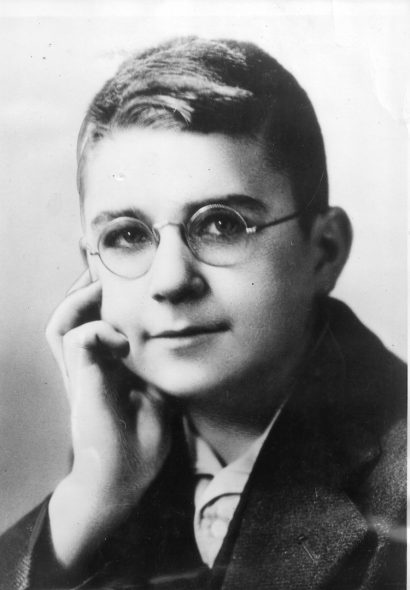

Anna Louise Sullivan was unremarkable. She was thin and small, and her short brown hair was streaked with gray. Her brown eyes peered through steel-rimmed glasses. Dressed in worn, dull-colored clothing with her shoulders sagging and her face aged by a lifetime of hard work and hard times, Anna was a person you would pass in the street and immediately forget.

“Everybody makes mistakes,” she said. “There’s no angels. I’m not perfect; I’m good when I’m good, and when I’m mad I’m mean.”

She was mean enough to have murdered her second husband and her eighteen-year-old stepson. Anna was mean enough to have attempted to kill her third husband and eleven-year-old stepdaughter, both of whom ended up in the hospital suffering agonizing pain and partial paralysis.

They displeased her in various ways, so she prepared meals for them containing a generous pinch of Paris green, a then-common commercial product used to rid homes of rodents and insects, which, given that it contained more than 50 percent arsenic, it did very effectively. (It was also used as a fabric dye, giving cloth the striking emerald green hue for which the product was named.)

Anna was not shy about discussing her crimes with reporters, and she described the product in detail. “It’s the funniest stuff. Real green, and so fine—like face powder,” she said. “You just take a pinch, like you would a pinch of salt, and drop it in the soup and it disappears. It don’t taste either.…I wouldn’t know. But Jimmy didn’t say nothing.”

Born in Oklahoma, Anna had a hardscrabble upbringing. She went to work picking cotton when she was just twelve. She met Ed Murphy, and the couple moved to Wisconsin, where Anna gave birth to five children, all girls. After Murphy’s death in 1927, Anna quickly remarried. Her new husband, Fred Ricklefs, was, in Anna’s description, unstable and abusive. But she felt she had little choice.

“It was too hard with five kids,” Anna said of her second marriage. “I had to get a man. But he was crazy from the war. He’d grab me by the hair and whoosh me all over the floor.”

Fred Ricklefs died in 1931 after Anna spiked his moonshine with poison. She told District Attorney Herbert J. Steffes, “It was funny when he went to the hospital. They thought he had appendicitis, because he had a pain in his belly.”

It was not a match marked by great passion. Anna told authorities she married only reluctantly. For his part, Mike said, “I needed somebody to take care of the children and the house.”

Anna moved into Mike’s little frame house on North Aster Street. Mike told investigators the couple had minor quarrels that were soon patched up.

Anna explained, “I tried to get along with him at first. I’d shake him up to make him mind, but after a while he was always mean. I never went any place. I had all I could do getting the kids off to school and cleaning the house. I never had no time even to see the neighbors.”

That fall, Anna urged him to take out life insurance and even arranged for a salesman’s visit. She also asked Mike to make out a will and told him she supposed he would make her the beneficiary.

Then the poisonings began.

Mike Sullivan arrived at the county’s general hospital on December 17, 1938, suffering from arm and leg paralysis. His symptoms suggested poison ingestion, but medical tests were inconclusive. After 12 days, his condition improved enough for him to be released. Mike returned on January 10 and was still in the hospital when his daughter Theresa was brought in with identical paralysis and a kidney condition. On April 27, son James, eighteen, joined his father and sister in the hospital. Suffering from abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea and sores in his mouth, he died the next day.

When an autopsy revealed arsenic, doctors notified authorities, and Anna was brought in for questioning. She denied any wrongdoing at first, but as the interrogation continued late into the night, she broke down and confessed to the district attorney, “I didn’t like them, so I put Paris green in their soup.”

Neighbors of the family were not entirely surprised. Mike Sullivan, a county parks employee assigned to Juneau Park, and his children had always been in perfect health until he remarried a year previously, after which they seemed to be constantly ill.

One neighbor said, “James came back from a CCC [Civilian Conservation Corps] camp last summer in fine physical condition. A little while after he came home, he got sick. Now he’s dead.”

Having confessed, Anna was taken to court for arraignment. She was quite calm, answering questions politely. During a recess, she joked with reporters and police, saying to Detective John Zilavy: “You got me pretty mad last night. You know what I do when I get mad.”

An onlooker suggested, “Why not invite him up to the house for a bowl

of Paris green soup?”

“That’s a good idea,” she chuckled. “I’ll do that some time.”

When court resumed, Anna was advised of her rights and entered a guilty plea. Taking the stand, Anna said she poisoned James Sullivan because “he wouldn’t do anything for me, and when I get mad I can do anything.”

From start to finish, investigators and newspapermen alike found Anna’s behavior puzzling. She appeared to be sane but completely lacking in remorse for having murdered her second husband and her stepson and attempting on two occasions to kill her stepdaughter and third husband.

“Those were pretty good pictures of me in the papers. I look good on the front page. When my mother saw that I bet she said, ‘My, there’s Annie,’” she smilingly told a Milwaukee Journal reporter just before walking into the courtroom to receive a life sentence.

The article the reporter filed was headlined, “Is Her Heart of Stone?”

Historic Milwaukee Crimes, a new book by Carl Swanson, published by Arcadia Publishing and can be purchased here.