Student Poverty Data Flawed

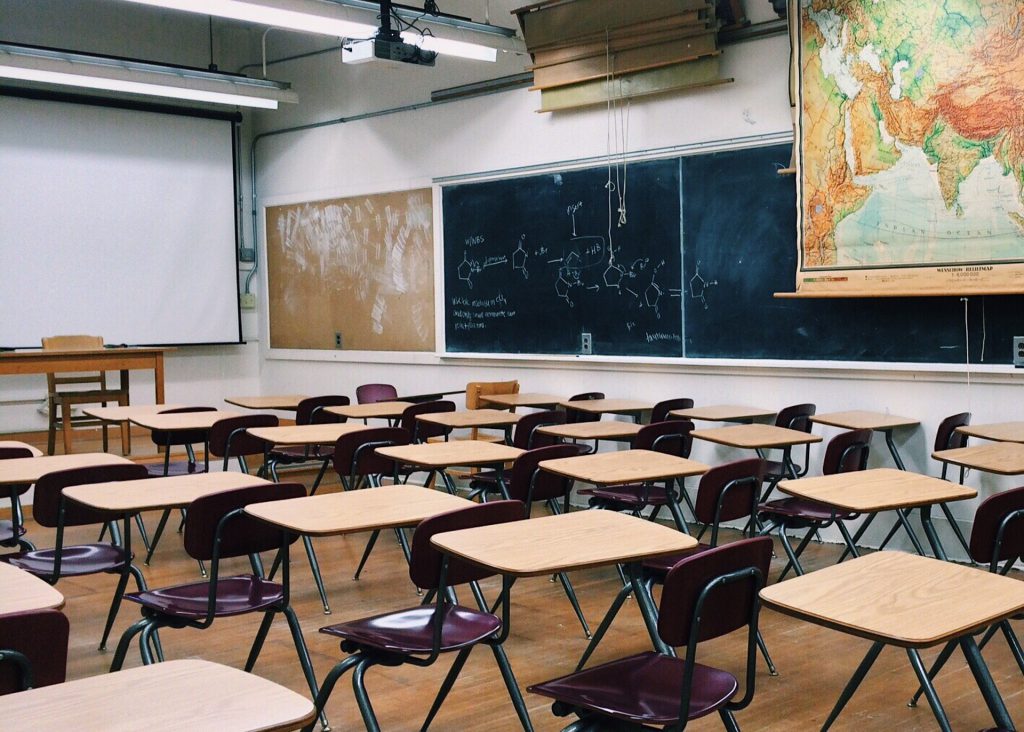

Poor measures of student poverty complicate charter school debate.

On July 29, the Milwaukee school board will formally receive a letter from Milwaukee College Prep charter schools announcing that it is ending its relationship with Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS). College Prep’s plan is to transfer its charters to UW-Milwaukee, taking with them some 2000 students. The dispute between the schools concerned additional payments College Prep believed it was entitled to; MPS felt differently.

This is the latest chapter in a series of conflicts MPS has had chartering independent schools. Some claim the school system is pushing away these charters because the district wants total control of the education of its students, others say it is bowing to the wishes of the teachers’ union to ensure that as many teachers as possible are unionized.

Key to answering this question is how the classification of economically disadvantaged students is judged. And here the data is not very good.

When College Prep made its announcement that it was leaving the district, MPS was quickly criticized by charter school advocates for not supporting a highly successful chartering organization. They pointed to the fact that both MPS and College Prep had very similar percentages of economically disadvantaged students, around 80%. Yet College Prep’s state report cards showed that its schools exceeded the state achievement standards while most MPS schools and the district fell far below those same standards.

Northwestern Mutual CEO John Schlifske followed up by stating that his company would now shift much of its support away from MPS to supporting private and charter schools.

Larry Miller, the recently retired Milwaukee school board president, blasted both moves. He contended that College Prep was not teaching the same group of students — that the economically disadvantaged backgrounds of College Prep students were strikingly different from MPS students. While charter schools are prevented from screening students, College Prep was screening parents. He contends that the school was looking for only students with parents that would support their children academically.

College Prep provides no bus transportation, Miller pointed out. Parents are pressured into signing school involvement agreements. These charters have a much lower percentage of special education students.

“Many MPS parents would love to be more deeply involved in their child’s school,” wrote Miller in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. “But working more than one job and taking more than one bus, having no affordable child care, no flexibility on the job, the threat of firing or lost pay if a child is sick – these are all real barriers parents face.”

Robert Rauth of College Prep sought to counter many of these claims stating his schools have been “providing an uncompromising education to Milwaukee children for nearly 25 years.”

Left on the table was a fundamental question of whether the 80% of economically disadvantaged students at College Prep had a similar income status when compared to the 80% of economically disadvantaged students in MPS.

Economically disadvantaged data flaws

Economically disadvantaged data has severe limitations, and experts who study student poverty question the use of this data as a measurement of student poverty. Yet advocates supporting charter/private schools continue to use this measurement, drawing questionable conclusions that charter/private schools do a superior job compared to public schools of educating economically poor students.

Economically disadvantaged has been historically used for measuring counting the students who qualify for free and reduced-priced lunch (FRPL). Free lunch eligibility for a family of four in Wisconsin is pegged at an income below $34,450 per year or 130% poverty level. Reduced-priced lunch for a family of four is available for families making up to $49,025, or 180% poverty level. Nationally about 60% of all children qualify for FRPL.

Nor have things changed much in recent years. Writes Satya Marar in a June 23, 2020 article for Reason, Best Practices For Identifying Student Poverty – Reason Foundation, “While eligibility for the federal government’s National School Lunch (NSL) program remains the most widely-used measure [of student poverty], it suffers from a number of issues that reduce its effectiveness in identifying the concentration of poverty.”

New measurement systems are developing as some school districts move away from national lunch statistics to “community eligibility.” School districts (like Milwaukee) can qualify for community eligibility if 40% of their students can be shown to meet the economically disadvantaged standard. Here every child receives a free lunch and often breakfast. The school system no longer requires individual families to fill out applications nor is eligibility checked when students go through the lunch lines. The administration of FRPL costs as much as simply giving everyone a free meal.

Community eligibility may use data from Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program, Title-I, Medicare (called BadgerCare in Wisconsin) and a host of other anti-poverty programs used to support lower-income families. Milwaukee Public Schools and other school districts use these alternative data collection systems to reach that 40% metric.

Clouded data

Community eligibility actually makes it much harder for researchers to analyze school poverty data. The data is often imperfect and adjustments must be made to the data in order to match the 180% rate used to calculate free and reduced price lunch. An additional problem is that both the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction and Milwaukee Public Schools, along with other school districts, do not disaggregate the levels of poverty for those students being classified as economically disadvantaged.

At one end of the scale, we have students who live in deep poverty, 50% below the poverty minimum. At the other end, a family of four’s income may be approaching $50,000 a year. Yet they all are considered economically disadvantaged.

The Learning Policy Institute’s Peter W. Cookson, Jr. outlines how school systems can measure economically disadvantaged students in the group’s May 2020 publication, “Measuring Student Socioeconomic Status.”

“There is a tremendous difference between levels of poverty, and we know levels of poverty have a lot to do with what happens in school and kids, what they bring to school and how they survive,” Cookson told the Examiner. “The current measure of free and reduced lunch masks these differences, and they are dramatic and documented.”

Cookson sees similar problems with many measurement systems. “Studies have shown that simply classifying people as ‘in poverty’ or ‘not in poverty’ is not sufficient,” writes Cookson in an article on deep poverty for LPI. “…families living in deep poverty face profound material, social, and emotional hardships. Households in deep poverty suffer from food shortages, unemployment, unstable housing, inadequate medical care, electrical shut offs and isolation.” The status of deep poverty has huge implications for the education of these children.

Cookson quotes Stanford researcher Sean Reardon on a national study of racial segregation and achievement gaps: “The experiences of children living in families with incomes just below the poverty line are likely different from those living in extreme poverty.”

Says Cookson in his 2020 publication, “Because FRPL is a dichotomous measure, it does not capture meaningful differences between students in extreme poverty and students from families that have some stable income. In the lived experience of students, levels of family income matter, as they directly impact access to material and nonmaterial resources.”

Nevertheless, in Wisconsin, the first determiner listed on the DPI website for economically disadvantaged is still Free and Reduced Price Lunch. However, other systems can be used. Knowing how many districts may be using alternative systems may be difficult to determine at this time given the pandemic and the degree to which students were using school food services this past year. Going forward, there could be an increase in the use of alternative data collection systems.

Measuring student poverty

The clouded and wide-ranging statistics leave an incomplete picture of the level of poverty of students. Without breaking apart the broad income data, we do not know what percentage of students live in deep poverty, marginal poverty or somewhere in between. Nor, at the other end of the scale, is it clear what percentage of our students come from the working, middle or upper classes.

Other data points that can be used to provide clarity between economic status include such measurements as student mobility, levels of parent education, age of the parents and a host of other variables can be analyzed using a robust statistical measurement system where we can pinpoint exactly which variables are the most important and which ones are not.

Questions that remain unanswered include whether alternative schools are being used by the marginally poor to flee schools that are housing the deeply poor. Whether stratification into different levels of poverty is taking place or not, the goal which has not been met is discovering which schools are doing the best job educating the poorest children.

Experts who may not agree on many other issues surrounding education, agree on this: To continue to compare schools’ achievement levels by using a simplistic measure of economically disadvantaged is unlikely to enlighten how our poorest children are being educated.

The limits of student poverty data was originally published by the Wisconsin Examiner.

K-12 Education

-

MPS Training in Science of Reading Going Poorly

Nov 23rd, 2025 by Terry Falk

Nov 23rd, 2025 by Terry Falk

-

The Fear Factor at MPS

Nov 11th, 2025 by Terry Falk

Nov 11th, 2025 by Terry Falk

-

MPS Reaching Out to Community

Nov 2nd, 2025 by Terry Falk

Nov 2nd, 2025 by Terry Falk

Students and parents are voting with their feet on where they can get the best education. And yes, this will leave behind in MPS those young children without caring and capable adults in their lives. All the analysis in this article is simply describing the problem.

Regarding how to address the problem, I will say this: Virtual schools, technology solutions and large class sizes will not work.

Germany has the best school system in the world. Milwaukee had one of the best German school systems in America. Why not use the German system, once again? I’m sure that Germany and the Germans won’t mind.

Do this and Milwaukee will be the #1 school system in America.