The Remarkable Art of Shari Urquhart

A monumental exhibition presented by two galleries of a little known Racine artist is a must-see event.

Rarely have two galleries in Milwaukee jointly presented one show, but given the number and size and quality of the works involved, the smallish Portrait Society Gallery and The Warehouse, with its 4,500-square-foot gallery, decided to collaborate on a remarkable exhibition of the largely unknown and never-shown textiles and watercolors of Shari Urquhart. Entitled “Mustn’t Touch,” it presents the best of a lifetime of work by a Racine-born artist who lived for decades in New York and created an unusual body of work: big, colorful, dramatic, often funny woven works. While her work was shown at a number of shows over the years, and several museums purchased her watercolors, she created no ripples in the art world. This show will surely change that.

Urquhart, who was born in 1940 in Racine and grew up in Kenosha, knew from a young age that she wanted to be an artist. She attended UW-Madison for her undergraduate and graduate studies, which she completed in 1967. After getting her MFA in painting Urquhart stayed on in Madison for a few years where she and a friend opened a store where they made and sold hand-printed fabrics and she started doing rug hooking. She never distinguished fine art from craft, but just liked to make beautiful, meaningful things. At the time Art Forum magazine was based in California which was highlighting figurative work in contrast to the dominant New York Abstract Expressionists, which gave Urquhart some encouragement for her own work. (The magazine, however, later moved to New York and its aesthetic changed accordingly.)

She may have taken encouragement from Judy Chicago‘s “Dinner Party,” an iconic feminist art installation of 1974 celebrating traditional women’s craft as art. And Urquhart was influenced by her friend and painter Phyllis Bramson, a Chicago figurative painter and feminist. (You can see her work as the Portrait Society is now exhibiting a show of Bramson’s work as well.)

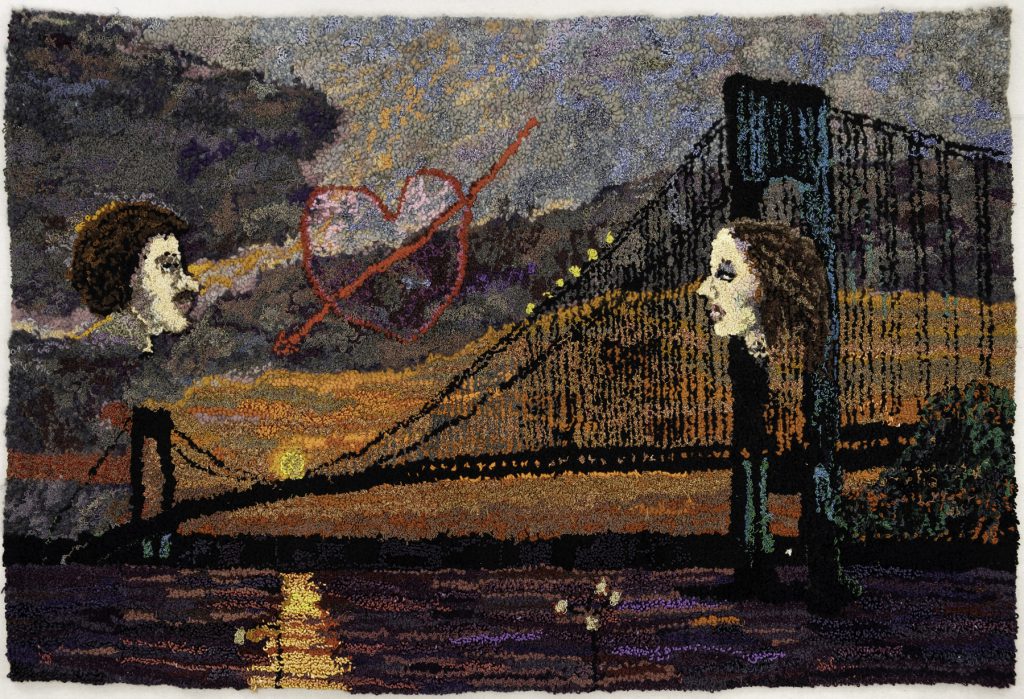

Urquhart started making textiles because she liked the ability to combine and use colors in a different way from painting, but her approach is still painterly. She juxtaposes and uses the yarn more like an Impressionist or Pointillist allowing the colors to mix optically in the eye of the viewer. She also liked the illusion the thickness of the yarn created, with other details embedded in the threads adding depth and an impasto-like character to the pieces. They work as a trompe l’oeil painting might, appearing sharp from a distance but densely rich and almost abstract as one gets closer and can see all the incredible variations, shadows, colors and textures.

Urquhart was constantly experimenting with various materials in the textiles, with yarn, metallic threads, dog hair, plastic — whatever could create the effect she wanted. They were based on watercolors which she first created and are paintings in their own right. There are only a few of these left, but from those exhibited one can see how carefully she composed the textiles. Making one of these pieces must’ve been similar to painting a fresco. The largest pieces are 10 feet by 12 feet and there are 10 of them. Each took a year to complete. Any correction would’ve been a lot of work on top of the amount of time needed to create the work in the first place.

By 1982 she had started working at the St. Francis Residence in New York, a non-profit which serves seniors and patients with mental illness. She established and ran an art program teaching painting and crafts which still continues. After retiring from St. Francis Center in 2007, Urquhart moved back to Kenosha, where she still had family and friends, and bought a house with a garden, which made her very happy. And she continued to create art, living there until her death at the age of 80 just a year ago.

The exhibit is divided into four chronological sections. The first is at the Portrait Society, and includes some of the artist’s earliest work, from the late 1970s and early 1980s. These are charming semi-autobiographical domestic scenes of couples, with touches of humor, and showing Urquhart already displaying her unique vision.

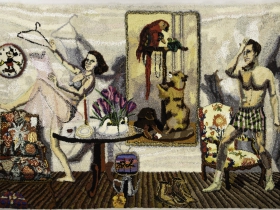

The rest of the work is at The Warehouse, in three sections. The first and and largest section is also semi-autobiographical work with genre scenes often set in apartments with a man and a woman engaged in various activities. But these are huge, with the figures almost life size. The men are often in boxer shorts and the women in a semi-sheer nightie or slip. The women are very much active and on equal footing with the men. The narratives feel feminist, but in a laid back, gentle way. The scenes are lively, good natured, intimate and cozy.

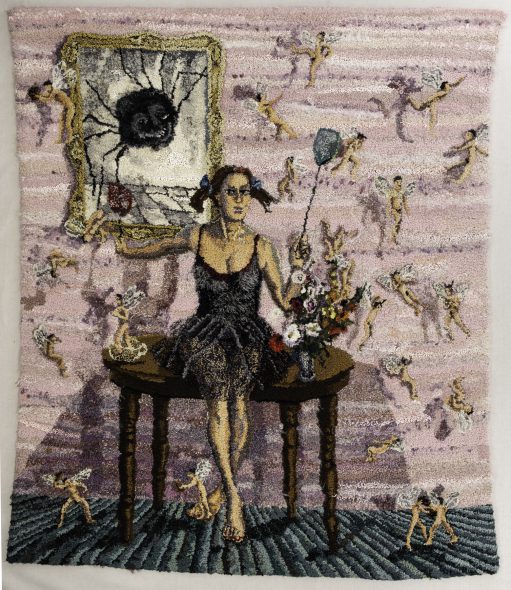

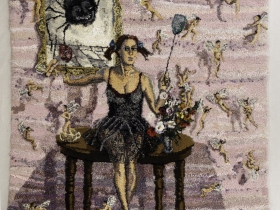

Urquhart plays with stereotypes. There are lots of ballerinas in pink tutus, usually the ultimate symbol of femininity, but here they suggest strength and discipline. One of my favorites is “Woman I, Stage III,” from 1995, where the ballerina dressed in a sheer black dress becomes part of the still life, but not as an object to be ogled. With a fly swatter she is swatting at pesky little flies that on closer inspection are little men doing manly things like tossing a football. A framed picture of a big ugly spider, a nod to an Odilon Redon painting stares menacingly over the woman’s shoulder. But this Miss Muffat is not frightened; she is clearly in charge.

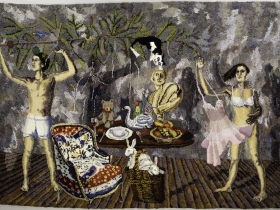

The very large domestic interior scenes follow the dictates of one-point perspective creating a depth into the frame like a stage scene. “Indecorous Deconstruction with Tree and Bunny,” 1985-86, celebrates the end of the holiday season and taking down the Christmas tree. Could it mean the end of the relationship too? A basket on the floor in the center holds two white rabbits, like those used in magic shows. A large table in the center has various objects including a Classical bust of a man, a lighted candle (used in most of the compositions), a teddy bear, a bowl of fruit, a place setting for dinner and in front of the table is an intricately patterned chair. Ornaments and tinsel and a cat seem to be falling from the sparse tree the man holds up over his head while his partner is on the opposite side in her underwear holding the pink ballerina dress.

These works show a vocabulary she developed of recurring themes and images, like a table with a still life which might include a toy castle, ballerinas, the lighted candle, food, stuffed and real animals, and more.

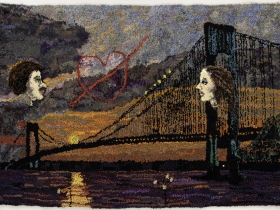

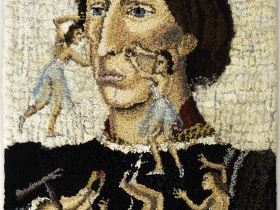

The second section at The Warehouse references art history directly and often cheekily, with textiles based on portraits and other works from the Renaissance and Baroque periods. “Woman with Big Squirrel” is an almost exact rendition of a painting by Hans Holbein the Younger entitled “Lady with Squirrel and Starlings” from 1526. The starlings are there, too, but very dark above her shoulders.

“Accessorized III-Cecelia” is based on Leonardo Da Vinci’s alluring portrait of the mistress of a Milanese nobleman whose nickname was “the ermine.” (The painting actually visited the Milwaukee Art Museum some years ago.)

The irony of these works is that Urquhart was apparently terrible at art history and repeated the class three times in college to achieve a good grade. Yet there is a love of these works that is palpable. And these, too, often include her own version of putti, the little angels found in those old religious paintings: hers are ballerinas and little men, the latter often with with wings.

The third section at The Warehouse are some of her smaller works, including watercolors of flowers and her garden and gorgeous rugs of colorful flowers.

After Urquhart’s death, her family reached out to Portrait Society curator Debra Brehmer to handle the work. She contacted John Shannon and Jan Serr at The Warehouse, who agreed to collaborate on a show. This is the biggest solo show of Urquhart’s art ever presented, and most of these works have never been shown before. Brehmer hopes to eventually tour the show, and is convinced the art world will be stunned by her artistry. It certainly stunned me.

“Mustn’t Touch” Gallery

The show runs through June 25 at the Portrait Society, 207 E. Buffalo St., #526, and The Warehouse, 1635 W. St Paul Ave.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

Art

-

It’s Not Just About the Holidays

Dec 3rd, 2024 by Annie Raab

Dec 3rd, 2024 by Annie Raab

-

After The Election Is Over

Nov 6th, 2024 by Annie Raab

Nov 6th, 2024 by Annie Raab

-

The Spirit of Milwaukee

Aug 30th, 2024 by Annie Raab

Aug 30th, 2024 by Annie Raab