Laughter In the Face of Terror

Jewish Museum’s show of Erich Lichtblau’s art is a daunting yet somehow delightful documentation of a Nazi slave camp.

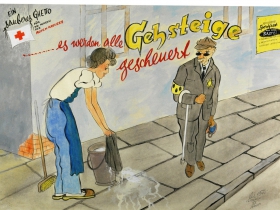

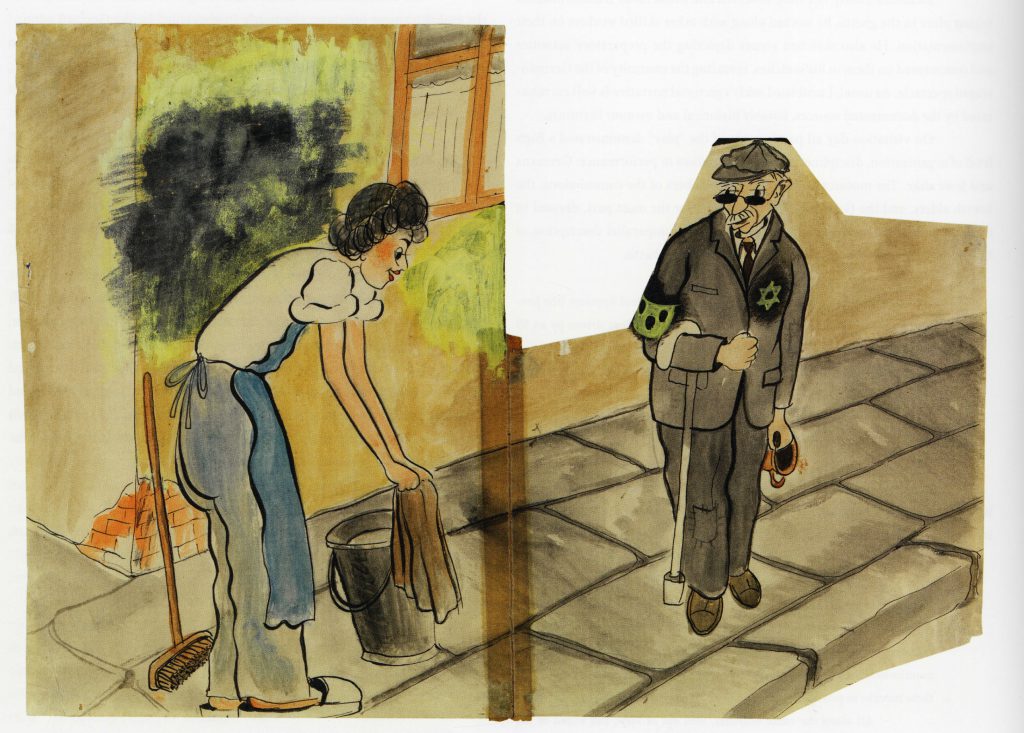

All Sidewalks Will Be Scrubbed. Ghetto period, Terezin, 1943. By Erich Lichtblau Leskly. This is exhibit is on loan from Holocaust Museum LA.

The Jewish Museum Milwaukee has reopened and features a remarkable exhibition: “To Paint is to Live: The Artwork of Erich Lichtblau.” These 65 drawings and paintings are a rich trove of art, a unique documentation of an artist who survived a Nazi slave camp and may have been saved by his art.

Erich Lichtblau Leskly was born in 1911 and was a graphic artist and designer from Ostrava in the Czech Republic who signed his art works as “Eli”. During World War II Lesky and his wife Else were deported and enslaved by the German Nazi army at the Theresienstadt (Terezin) interment camp about 40 miles north of Prague.

Terezin was unique in that it also served as a “model” camp to fool the outside world as to the reality of the Nazi concentration camps. When visitors came to inspect it, the town was staged to appear as a pleasant and well appointed relocation camp. To create a less crowded environment hundreds were sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp. The Nazis even went so far as to call the camp a “spa”!

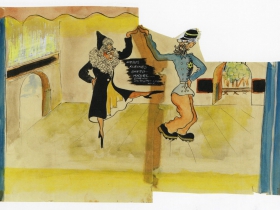

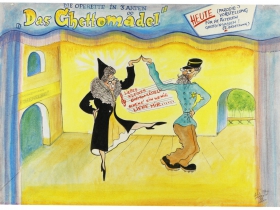

Erich was assigned to various jobs including doing propaganda artwork for the Nazis, thus allowing him access to art materials. The art he created secretly, his sketches and cartoons, gave him a purpose and helped him to endure four horrendous years in Terezin. He was old enough to be patient and not take chances, but still young enough to have a sense of the absurd and sardonic, which can be seen in his art. Other painters who were making art related to camp experience were found out and all sent “East” which meant to concentration camps in Poland, but Leskly’s work was never discovered.

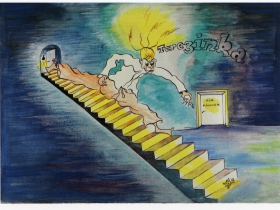

It was Else who suggested they cut up the “cartoons” and hide them under the floorboards. The text was cut out out before hiding the colored pencil drawings. After liberation by the Soviet Red Army in 1945 Else went back and rescued the hidden colored pencil drawings. The original drawings were like pieces of a puzzle, but were later taped together and displayed with the large watercolors Erich recreated from the fragments in 1970. This exhibit comes from the archive of Los Angeles Holocaust Museum.

Erich’s paintings show not only the extreme suffering of the inmates due to malnutrition, brutal labor and weather conditions, but also the methods used by the Nazis to control and dehumanize the prisoners as evidenced by his portrayal of a man in the cage being shown as an example to other prisoners.

Some of the paintings refer to the diseases which plagued the camp: encephalitis, Scarlet fever and one nicknamed Terezinka — a type of typhoid fever caused by contaminated water and food.

No, this doesn’t sound very humorous. But Eli’s style is loose and gestural with exaggerated facial contortions and the cartoon-like imagery can bring a smile to your face even when the subject is grim. His memory did not fail him when he recalled these scenes in the later watercolors he created, and they capture the sense of the spaces and the environment in which the inmates lived.

Small acts of kindness are treasured and celebrated in the works — like giving someone a cigarette or women gathered around a little stove to share a meager meal and warm themselves. And the work is often ironic about the Nazi attempt to destroy the wills of the inmates. Yes, the stories of this time have been previously documented, but this work is primary and very moving because of the authenticity and unique personal vision of the artist.

The show also includes a short animation created using the paintings from the exhibit. The last scene is particularly poignant. A prisoner sits against a wall smoking a precious cigarette and looking towards a town near the camp where life is going on as normal. It’s so close and yet so far away.

I was so relieved to learn that Eli and Else survived Terezin and were able to move to Israel and have a family. They both lived to old age. So a happy ending, although the memories never went away and it was still painful for them to talk about the experience. Which adds more power to the show.

“To Paint Is To Live” Gallery

“To Paint Is To Live,” through May 30, Jewish Museum of Milwaukee, 1360 N. Prospect Ave.

Art

-

Winning Artists Works on Display

May 30th, 2024 by Annie Raab

May 30th, 2024 by Annie Raab

-

5 Huge Rainbow Arcs Coming To Downtown

Apr 29th, 2024 by Jeramey Jannene

Apr 29th, 2024 by Jeramey Jannene

-

Exhibit Tells Story of Vietnam War Resistors in the Military

Mar 29th, 2024 by Bill Christofferson

Mar 29th, 2024 by Bill Christofferson