Lessons of the 1969 MATC Strike

How public employees beat the odds to create a union.

On the tenth anniversary of one of the darkest days in Wisconsin history — the introduction and subsequent passage of Act 10 — it’s important to recognize that unions in the past have grown and even triumphed under similar conditions that former-Gov. Scott Walker, Speaker Robin Vos and now-Congressman Scott Fitzgerald and their co-conspirators imposed on unions.

As bad as things are now, 1969 presented different but daunting challenges to union organizers: no dues checkoff, news media hostile to unions, no precedents for public-employees improving bare-bones contracts.

The time is ripe for review as tides are changing under the new administration. One of the first things President Joe Biden did upon taking office was to fire the Trump-appointed National Labor Relations Board general consul, infamous for union busting.

It’s clear, though, that public employees and private sector workers can’t rely on politicians alone to rebuild their unions. Union advocates today, however, can look to the past for lessons in constructing union power that are never too old to relearn.

Faculty as hall monitors

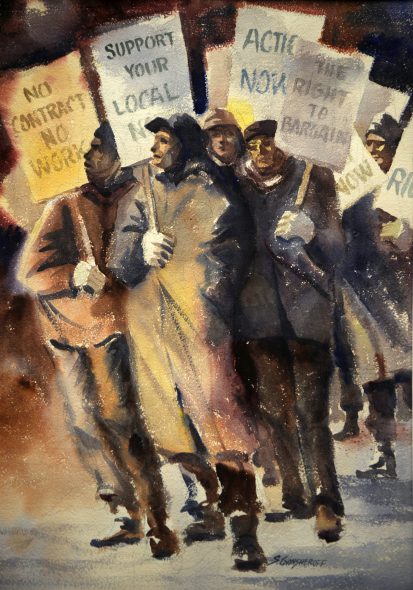

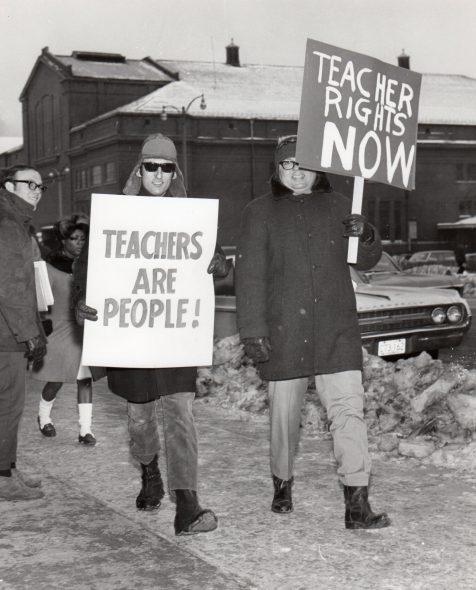

Fifty-two years ago, during a Wisconsin winter much colder than this one, the faculty union at Milwaukee Area Technical College (MATC) went on strike for forty days. Given that public employees couldn’t legally strike, these members of the American Federation of Teachers Local 212 risked their careers, not only to benefit themselves and their families, but so subsequent generations of faculty would be treated and compensated like the professionals they were.

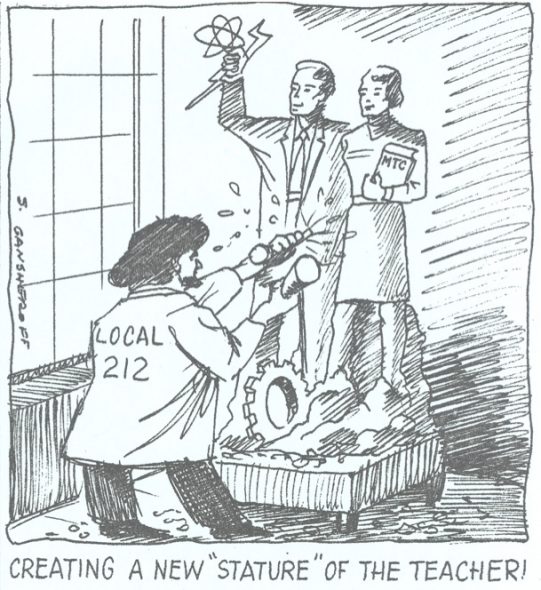

Their eventual victory resulted in much more than a vastly improved contract. This strike transformed MATC into a world class institution because for the first time it gave classroom professionals a decisive role in the direction of the college, it inspired public employees across the state and nation and it reinforced the bedrock strategic principle that labor historian David Brody summarized as “First power, maybe cooperation.”

Local 212 was no stranger to victories. The faculty union at Milwaukee Technical College, as it was called then, played a key role in persuading the Wisconsin Legislature and Gov. Gaylord Nelson to pass a law in 1959 making Wisconsin the first state in the nation to grant public employees collective bargaining rights. But negotiations were slow against a recalcitrant administration. While Local 212 achieved the first higher-education union contract for faculty in the country, it took four years to do it, and the result was a spare, 12-page document.

The college administration, resentful of having given up even a smidgeon of its previously absolute power, continued to treat the faculty like hired hands who should do as they were told and keep their mouths shut. Administrators gave faculty no say in curriculum or even textbook choices, and they required these professional educators to punch time clocks and serve “monitor duties” in hallways, the cafeteria and building entrances.

The decision to strike was not an easy one. Many of the teachers like Jack Misorski and Paul Jagielski, who had just been hired by MTC in response to the post-WWII baby boom enrollment in higher education, had young families and little savings. In addition, Local 212 did not have dues check-off, so new teachers were being asked simultaneously to risk their jobs and voluntarily pay dues.

But 212 leaders had a plan to build power.

Mobilizing to win

First, they focused on growing membership and militancy based on the day-to-day indignities instructors faced. They surveyed the faculty about problems created by deans in various departments and how these affected their capacity to effectively teach students. Then they formed a “212 Action Committee” to publicize to all departments the ridiculous and unprofessional actions of deans throughout the campus.

When it became clear from mass meetings how disgusted the faculty was with unreasonable administrators, 212 organized for the strike by forming committees for internal publicity, media contacts, poster and picket sign creation, strategy, finances and research. The latter uncovered and publicized that the administration’s claim of a budget crisis was a canard. A phone squad enabled rapid communication, using the tools available at the time, with the membership.

This preparation occurred during a period ripe for activism. The numbers of public employees had spiked in the fifties and sixties, but because they were excluded from the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, they were underpaid compared to the private sector, and dissatisfaction was rampant.

A cohort of veteran teacher-activists built power and support among their peers in a systematic way, preparing to demand wholesale changes in how MATC functioned.

High on Local 212’s list of demands was the idea of shared governance. The administration typically allowed little input from faculty on key educational issues. Several department deans were absolute dictators who allowed no instructor input to modify or adapt curriculum. In response, the union demanded that all college committees include faculty representation to ensure that those who worked directly with students would have a voice in college decision making. Another demand was ending mandatory non-teaching duties like lunchroom monitoring.

The 212 leadership was very aware that they also had to build power throughout the community. Student government at MATC fully supported the striking teachers, and very few students crossed the picket lines to attend classes despite threats from the college administration. A group calling itself The Student Liberation Union (SLU) organized support for the strike and wrote in the MATC Times, “If these demands are not met, this institution will continue to provide overworked instructors, fail to attract adequate new teachers, inhibit classroom functions, and destroy what effectiveness the facilities still retain. Don’t let yourself be fooled into accepting a second-class education.”

The SLU was joined by other student groups including the Young Democrats and Young Republicans. During the second week of the strike, 200 students picketed with their teachers. Local 212 added to its demands a non-reprisal clause for students and instructors honoring the picket line.

AFT Locals from across the state and nation sent letters of support as did other labor unions. The United Auto Workers helped on the picket lines. The NAACP offered its support. While the union was diligent about issuing media releases and offering interviews, both daily newspapers and TV stations remained hostile to the strikers.

Part of building power was to come up with innovative tactics. For example, the business manager of the Carpenters Union was on the college board of directors, but he failed to advocate for the teachers, so Local 212 picketed the Carpenters’ Union, demanding he side with labor and urged other union leaders to put pressure on the Carpenters.

Victory

After 40 days on frigid picket lines without paychecks, Local 212 won the strike.

Having built power and then applying it, many of 212’s new contract provisions were about compelling the administration to cooperate with the faculty to improve the quality of education students received:

- Significant voice on curriculum

- Paid leave for professional improvement

- Department deans mandated to meet with faculty

- College president required to meet with 212 president

In addition, faculty made huge gains with bread-and-butter issues:

- Salary hike of 7%

- Grievance procedure

- College pays employee pension contribution

- Sabbatical Leave compensation

The most significant direct benefit of the strike was that the administration was put on notice that a failure to respect and cooperate with the faculty would result in serious repercussions.

In 2021, it’s clear that Wisconsin unions have been pummeled by the Republicans’ Act 10 attack on public employee unions followed by the so-called “right to work” attack on private sector workers. Rebuilding the middle class will be easier if the Biden administration lives up to its labor agenda. It will also take union leaders wise enough to learn lessons from earlier generations.

During a frigid winter 52 years ago, Local 212 demonstrated that through systematic organizing and creativity unions can build power, exercise it, and create the basis for cooperation that benefits workers and the community.

Michael Rosen and Charlie Dee are retired MATC instructors, Rosen in Economics and Dee in American Studies. Both were long-time leaders of AFT Local 212, Rosen as president for 17 years, Dee as Executive VP for 14 years. Dee co-authored a history of the ’69 strike, “Forty Days That Forged a Union.”

Reprinted with permission of Wisconsin Examiner.

Op-Ed

-

Wisconsin Candidates Decry Money in Politics, Plan to Raise Tons of It

Dec 15th, 2025 by Ruth Conniff

Dec 15th, 2025 by Ruth Conniff

-

Trump Left Contraceptives to Rot; Women Pay the Price

Dec 8th, 2025 by Dr. Shefaali Sharma

Dec 8th, 2025 by Dr. Shefaali Sharma

-

Why the Common Council’s Amended Budget is Good Policy for Milwaukee

Nov 20th, 2025 by Alds. Marina Dimitrijevic and Russell W. Stamper, II

Nov 20th, 2025 by Alds. Marina Dimitrijevic and Russell W. Stamper, II

I remember the strike of 1969 very well. I was one of those students who refused to cross the picket line and began walking the line with the activists instead. I remember that my teachers didn’t penalize me and my mother, a union activist of the 1930’s, was proud of me!

Chris Christie

The strength of the union at MATC contributed to the quality of instruction at that institution. AFT local 212 helped me immensely in learning how to teach MATC students. I have been retired for over seven years, yet I still encounter former students at grocery stores, or on the street, who remind me of a special bond between teachers and students at MATC.

.