State Superintendent Candidates Debate

Seven candidates include teachers, principals, superintendents and policy experts.

The seven candidates vying for the post of state superintendent are all hoping to put forth a vision for bringing Wisconsin’s schools out of the chaos of the pandemic and into a more equitable future. It’s a field crowded with teachers, principals, superintendents and policy experts with years of experience and perspective. They all hope to distinguish themselves before voters go to the polls in a Feb. 16 primary. An April 6 general election will determine which of the remaining two contenders will step into Wisconsin’s highest education post, overseeing the state’s more than 2,000 public schools.

In early 2020, State Superintendent Carolyn Stanford Taylor, appointed by Gov. Tony Evers to replace him, announced that she would not seek another term in the spring election.

At a Jan. 8 online candidate forum sponsored by the League of Women Voters and the Wisconsin Public Education Network (WPEN), the candidates shared visions for the future, including detailed plans for addressing some of Wisconsin’s most egregious educational inequities.

Heather DuBois Bourenane, executive director of WPEN, introduced the event, saying, “We’re here tonight because the Feb. 16 election matters deeply to every single one of us and to every single kid in this state. The person we elect to lead the Department of Public Instruction will not only write the next budget and drive policy for our schools, but will be our lead advocate and inspire others to join us in fighting for the schools we know our kids deserve.”

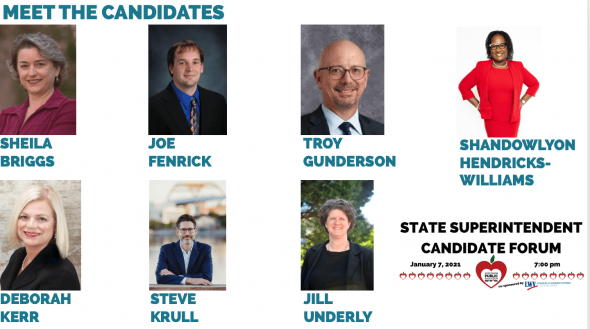

Debate moderator Tony Chambers, director of equity, inclusion and innovation at the Center for Healthy Minds at UW-Madison, introduced the candidates: Sheila Briggs, Joe Fenrick, Troy Gunderson, Shandowlyon Hendricks-Williams, Deborah Kerr, Steve Krull and Jill Underly.

Meet the candidates

Briggs, who currently serves as assistant state superintendent, said “public education is the best way to really improve the human condition,” adding that she has focused on equity in her roles as a teacher, principal and central office administrator. “Right now, we have unacceptable racial and economic achievement gaps in our state that we need to address,” Briggs said.

Fenwick, a Fond du Lac High School science teacher, geology lecturer and county board member, spoke of the importance of education to his family; he has four children, including a toddler and a high school student.

Gunderson, a retired superintendent from the school district of West Salem, near La Crosse, said he joined to race to “give back both to the state of Wisconsin and to public education.” His wife, mother and father-in-law were all teachers, and he said he is running on a platform of “leaders ready to lead, students ready to learn, teachers ready to teach.”

Kerr spoke of her experience as a charter school founder, teacher, athletic director and, for the past 13 years, superintendent of the Brown Deer school district, which she said is “one of the most diverse school districts in the state, serving over 80% students of color and 50% economically disadvantaged.”

Krull, an Air Force veteran and principal of Garland Elementary in Milwaukee, said “our schools are falling apart, and I am running because I believe we can rebuild our education system in Wisconsin.”

Underly, the superintendent of the Pecatonica Area School District called herself “a lifetime public education advocate” and “the only candidate is from a rural Wisconsin community currently leading a school district in a pandemic.”

After the debate was over, DuBois Bourenane said she was encouraged by the focus on equity. “COVID-19 has exposed all of these inequities that we’ve been trying to advocate around for years,” she told the Examiner. “When you’re running to be the head of schools in the state that has the biggest gaps for black and white children in all the states, you better be prepared to answer questions about it.”

Addressing COVID, inequities among rural, urban, and suburban districts

The candidates each had two minutes to put forth a “new normal” vision for education in a pandemic. “We have children who have lost their parents,” said Hendricks-Williams. “They’ve lost their grandparents, who might’ve been their primary caretaker. Young adults have now taken over raising their siblings because they’ve lost their parents and they don’t want to be separated from their brothers and sisters.” She praised parents and teachers for “stepping up to the plate.” The teachers are frontline workers, she added, proposing a COVID-19 checklist and safe protocols for distributing PPE in schools. “We need to acknowledge their hard work, thank them and elevate the field of teaching.”

Krull proposed a radical restructuring of school financing to eliminate inequities tied to property taxes. “This is a really good opportunity for us right now to look at the structures of what is failing inside of our system and not just do little things that cut across the edges,” Krull said. “Some districts get twice as much money as others per child. We can’t provide the same educational experiences when you have that much inequity.”

Underly outlined a host of specific reforms, including early childhood programs, mental health services and academic recovery opportunities, saying, “All kids, regardless of zip code, need 21st century classrooms.” She described technological inequities, including urban and rural districts that do not have access to broadband. “Most of all, we need to make sure that the most vulnerable kids are served and their programs are fully funded, and we need to appreciate and pay our teachers more,” she added.

Race and inclusion

A question submitted in advance by a Dane County student asked each candidate how they planned to make students feel safe in schools, including students with disabilities, BIPOC and LGBTQ students. Hendricks-Williams, the only Black candidate, recalled many times as a student and parent when she did not feel safe. She said she has written a 20-point student bill of rights outlining policies that will address “a feeling of belongingness in the classroom.” She said she wants to diversify the teaching pool, work with parents to create inclusive curriculum, and “infuse their educational experience with art music, gym, physical education and health, where they have an opportunity to show how smart they are in many different ways.”

Kerr recounted a racially charged incident in her district, after which she took action to create an anti-harassment and discrimination policy. Underly reiterated the need to recruit more teachers of color, and said she would create a cabinet-level equity office and invest in early childhood education, while Briggs advocated for anti-bias training.

All the candidates expressed concern about the overuse of standardized assessments and lack of funding for special education. Krull said he believes the testing that was part of the No Child Left Behind era shifted the focus onto tested subjects, reading and math, to the exclusion of creating well-rounded students. “We need social studies, civics and science and art and music, physical education. Kids don’t come to school excited just to learn math and reading,” said Krull. “You’re going to lose them.”

Fenrick concurred, adding that he and his daughter counted 26 days of testing out of a 180-day school year. “Now that’s an entire month where they could be reading or they could be learning hands-on activities,” Fenrick said. “All the tests have narrowed our curriculum. They’ve cut art. We have cut music, and our science programs.”

Hendricks-Williams said she worked at two schools in Milwaukee’s 53206 zip code that were able to bring students’ reading test scores up significantly by creating customized interim assessments. “One of the main reasons that we were able to increase our student achievement from 30% of our students reading on grade level to 70% was implementing quarterly interim assessments. This is what I mean by creating new trajectories, coming up with school-wide plans that meet students where they are.”

Public funding for private school vouchers and charters

In a lightning round, all the candidates were asked to give a “yes” or “no” answer to two questions. The first was whether they support vouchers for private schools. All the candidates answered “no,” except for Hendricks-Williams and Kerr, whose answers were unclear. Krull’s answer was the most forceful: “No, I think they’re destroying our whole public education system.” The candidates provided similar answers to the question: “Do you support non-district independent charter schools in the state of Wisconsin?” Hendricks-Williams replied, “I support parents’ options for enrolling their child in a high-performance school.”

Many Wisconsinites remain unaware of the severity of the school funding crisis in the state, or the decade-long moratorium on funding for English language learners, DuBois Bourenane adds. “Who’s going to fight to close the funding gaps? With effective and passionate leadership we could do better at educating the public and our lawmakers so that they could see what the impacts of these continued under-investments really are doing to kids and start taking steps to fix it. This race matters deeply to all of us, and to every kid and to every community in the state, whether your kids are in a public or a private school.”

Reprinted with permission of Wisconsin Examiner.

The answer that Hendrick-Williams gave on charter schools about allowing parents to enroll their children in “high performing schools”, is a position that politicians always say who support the School Choice Program. I think she needs to give a definitive answer on the School Choice program. Unless she does come out in opposition to the Choice program, she just might be the candidate supported by the conservatives who are tying to undermine public education.