Why State’s Voting By Mail Was Chaotic

And how Wisconsin could prepare for fall election by mail only.

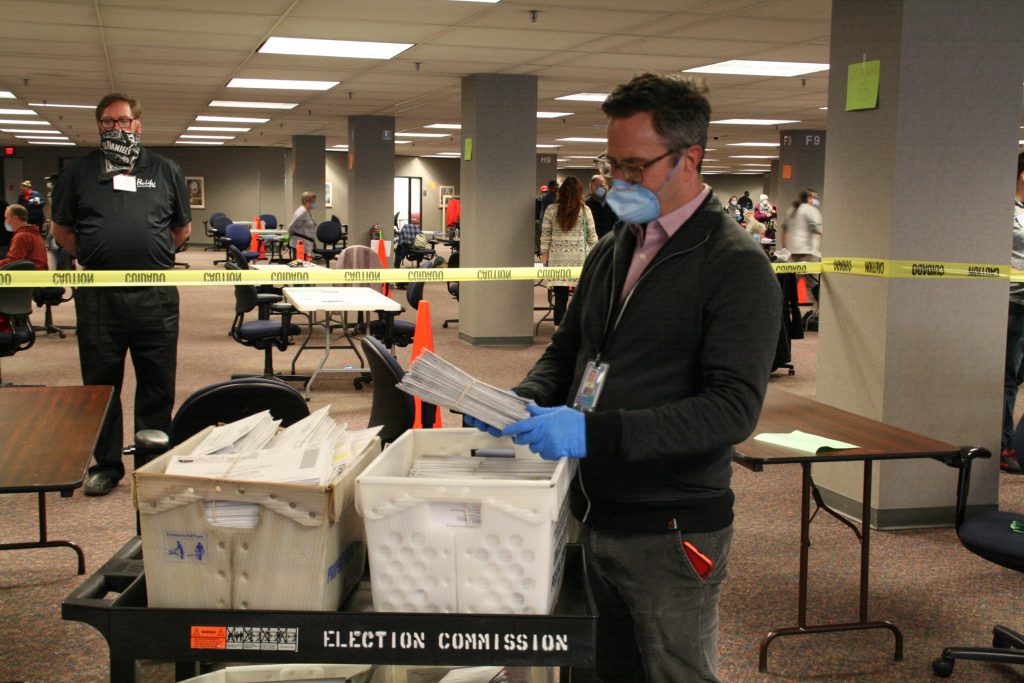

Milwaukee Election Commission Executive Director Neil Albrecht looks through absentee ballots. Photo by Jeramey Jannene.

Wisconsin’s primary election has become a cautionary tale for election administrators and public officials all over the country.

Nobody wants to see long lines of masked voters like Milwaukee saw on April 7 due to a lack of poll workers and polling places.

But the Wisconsin election also offered another lesson: moving voters to mail-in ballots isn’t easy, either.

More than 80% of Wisconsin voters cast ballots remotely in the April election, compared to less than 10% for most elections. In all, municipal clerks sent out 1.27 million absentee ballots. The sudden surge led to a host of problems, from a big spike in mailing costs for local authorities to ballots that never got to the voters they were sent to.

“But Wisconsin is not a state that is thought of having a poor election administration during normal times.”

In fact, Wisconsin had many policies in place that should have helped it cope with the challenges of holding an election during a pandemic, Berger said. For example, it allows voters to request absentee ballots without providing an excuse. It allows for early voting. It lets voters register online or in-person on Election Day. “There’s a lot of states in the same boat as Wisconsin, and there are about 40 states and D.C. that are in at least as bad shape,” he said.

One thing Wisconsin did not have, though, was experience dealing with huge volumes of mail-in voting. The local authorities didn’t have the infrastructure to handle the shift so quickly, Berger said.

Of course, several other factors complicated the process as well. The coronavirus public health emergency didn’t really emerge until after the initial stages of the election – printing ballots and allowing voters to request absentee ballots – were already underway. The rules governing the election changed several times in the final weeks, as Republican legislative leaders and Democratic Gov. Tony Evers clashed over how the election should be carried out, and various courts put new rules in place.

But if administrators in Wisconsin or around the country want to avoid a repeat of the problems with the state’s April elections, they need to start making changes right away, warned Amber McReynolds, the CEO for the National Vote at Home Institute and Coalition and a former elections director for the city of Denver.

“It’s not too late,” she says. “The clock is ticking, but the time to act is now.”

Voting by mail is complicated

Wisconsin election officials note that they have the “most decentralized state for election administration” in the country, with 1,850 municipal election officials and 72 county election officials.

“There are people who want to say, ‘Let’s just vote by mail,’” said Reid Magney, a spokesperson for the Wisconsin Elections Commission. “But no matter how complicated you think it may be, it’s actually more complicated than that.”

At the most basic level, there’s the matter of having enough ballots to meet voters’ demands. In Wisconsin, voters have to specifically request that their local clerks send them an absentee ballot for an upcoming election, although they don’t have to provide a reason. All they have to do is send in their information and a copy of a photo ID to the clerk. The clerk would look up their record, upload a copy of the photo ID to a statewide database and mail out the appropriate ballot.

The whole system was built to handle a relatively small percentage of voters, like those who planned to be traveling on Election Day. Local authorities expected that about 10% of voters would request the mail-in ballot. They budgeted for postage and bought the special envelopes for ballots based on those assumptions. Often, someone in the clerk’s office would stuff the envelopes themselves before sending them out.

But the flood of requests this year strained that system.

For one thing, clerks didn’t have enough envelopes to mail out their ballots and couldn’t find printers who could produce more of the paper stock they needed for the ballots. The Elections Commission had to help local authorities find vendors who could produce the ballots and envelopes.

The relatively simple-sounding task of mailing ballots back in turns out to be tricky, too.

While Wisconsin elections officials tried to encourage voters to request absentee ballots weeks before the election, state law says they can request one up until the Thursday before the election. That only allows for five days for the clerk to process the request and put it in the mail, the Postal Service to deliver the ballot, the voter to fill out the ballot in the presence of a witness and put it back in the mail, a mail carrier to return the ballot to the clerk’s office and the clerk’s office to receive it. (In the April election, a judge cut the time even closer, by making the deadline Friday instead of Thursday.)

“That’s insane,” said Tammy Patrick, a senior advisor for the Democracy Fund who serves as a liaison between elections officials and the Postal Service. “When the states allow that to happen, it sets the voter up to fail.”

The deadlines were set, said Magney of the Elections Commission, at a time when the ballots would go from a person’s house to the post office in town and then directly to the clerk’s office. Now, those ballots are likely to travel to Milwaukee or St. Paul to a sorting center before they’re sent back to the local clerk’s office.

One way that election authorities can avoid the problem of the tight turnaround is by relying on postmarks on the ballots, to make sure they’ve been sent by Election Day rather than received on Election Day. There’s just one problem with that: a lot of ballots don’t get postmarked.

Traditionally, the Post Office used postmarks to cancel the stamps on envelopes, so people couldn’t reuse stamps over and over. But a lot of business mail never gets postmarked, because the sender uses postage that’s printed directly on the envelope instead. A lot of ballots are sent in envelopes with prepaid postage.

Election officials have worked with the Postal Service to come up with a policy that says post offices are supposed to affix postmarks on envelopes that show they’re being used for ballots. Postal officials in Wisconsin even reminded local offices about that ahead of the April election. But the policy “didn’t happen uniformly,” Magney said.

States that rely heavily or exclusively on mail-in ballots print barcodes on the ballot envelopes that indicate that they are ballots. The post office can better track those envelopes and prioritize them, and the tracking lets voters check on where their ballots are en route to their clerk’s office. The Wisconsin Elections Commission has unanimously approved a plan to use a portion of the $7.3 million in federal elections money it is getting from a recent congressional rescue package to start using the bar codes on its ballot envelopes.

State elections officials are also considering whether to redesign ballot envelopes altogether, by using three envelopes. That would allow the outer ballot envelope to get to the clerk’s office more efficiently while still adhering to the law requiring the form on the outside of an inner envelope.

McReynolds, the former Denver election director, said Wisconsin jurisdictions could simplify the process of sending out absentee ballots by using outside vendors. The state could even coordinate the procurement process for local jurisdictions, as state agencies did in Maryland and Georgia recently, she suggested. McReynolds also said that larger jurisdictions in Wisconsin could acquire higher-capacity vote-counting machines that would be more efficient than using the tabulation equipment typically used in precinct polling places.

One option that isn’t available in Wisconsin that other states are using is to simply send out absentee ballots to all voters. State law makes clear that voters have to request the ballots in writing, and they have to include a copy of their photo ID.

Cash from Congress?

A major outstanding question, of course, is how states and localities would pay for all the costs associated with the shift to mail-in voting. Many election advocacy groups are pushing for Congress to step in. The Brennan Center for Justice, for example, is calling on Congress to spend $4 billion to help administer this year’s elections.

That money would cover everything from building up online voter registration capabilities to supplying poll workers and voters with hand sanitizer and protective gear.

But Norden said it’s up to the federal government to step in. States and localities can’t significantly reduce their election expenses, he said, because most still have to offer in-person voting options. (Some 70% to 80% of the new expenses will fall to local, rather than state, entities, according to the Brennan Center). That means they’re facing the prospect of running a “second election.”

“States and local governments don’t have money for second elections,” Norden argues. “The only entity that will have enough money to provide for safe and fair elections right now is Congress. I do think Congress has a responsibility to provide safe and fair elections.”

In Congress, he added, a lot of the political debate is about whether to allow mail-in voting, but that argument is moot, because most states now allow no-excuse mail-in voting. The pandemic changed voters’ behavior, not legal requirements. Wisconsin election officials, Norden said, “were forced to run an entirely new system on the fly without resources.”

“The question,” he said, “is whether we’re going to put the infrastructure in place … so we can do that safely and well, or are we going to be another Wisconsin?”

Reprinted with permission of Wisconsin Examiner.

More about the 2020 Spring Primary

- Why Don Natzke Couldn’t Vote - Enjoyiana Nururdin - Aug 9th, 2020

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report highlights public health measures taken by the Milwaukee Health and Fire Departments, Department of Administration, Election Commission, and the Wisconsin Department of Health Services - City of Milwaukee Health Department - Aug 4th, 2020

- CDC Says Election Did Not Cause COVID-19 Spike - Erik Gunn - Aug 4th, 2020

- Pandemic Reduced Black Vote, Study Finds - Dee J. Hall - Jun 25th, 2020

- Did April Election Hike COVID-19 Cases? - Alana Watson - May 20th, 2020

- Elections Commission Notes ‘Lessons Learned’ - Henry Redman - May 19th, 2020

- Wisconsin Elections News: WEC Releases Analysis of Absentee Voting in April 7 Spring Election - Wisconsin Elections Commission - May 18th, 2020

- Election’s Impact on County’s COVID-19 Cases Unclear - Jeramey Jannene - May 6th, 2020

- Why State’s Voting By Mail Was Chaotic - Daniel C. Vock - May 4th, 2020

- At Least 40 COVID-19 Cases Tied to Election in Milwaukee - Graham Kilmer - Apr 24th, 2020

Read more about 2020 Spring Primary here