Rethinking State Economic Policies

What do state policies on Foxconn and dairy industry have in common?

With a new administration in Madison—and the recent announcement of new leadership on the state development commission—this is a good time to rethink the role of economic development in Wisconsin. As a new report from the Upjohn Foundation‘s Tim Bartik suggests, “… governors and mayors … find it difficult to resist handing out large tax incentives to major corporations, ideally paid for by their political successors.”

Certainly, that fits the Wisconsin experience. The Foxconn subsidy is an extreme example of where the conventional process leads. Bartik notes that “The Foxconn offer, as a percentage of the facility’s value-added, is more than 10 times the national average, and 10 times Wisconsin’s typical incentives.”

Bartik lists two possible ways of helping people stuck in distressed places, place that suffer from a persistent lack of jobs. One is to help people move to more prosperous places. He argues that this strategy has several drawbacks ranging from people’s reluctance to leave their family and friends to the fact that loss of residents worsens a region’s economic distress.

In Southeastern Wisconsin, parts of Racine and Kenosha, in addition to Milwaukee, are economically distressed, left high and dry when their factories closed. An effective economic development strategy would target those areas and restrict subsidies to companies willing to bring manufacturing jobs to places like Century City on Milwaukee’s North Side. It would also identify existing small businesses that could be helped to grow.

Naming Organic Valley executive Melissa Hughes as head of the Wisconsin Economic Development Corp. is evidence that the new Wisconsin administration wants to break the bonds of the traditional economic development model. Several past Data Wonk columns looked at the crisis in dairy farming. The problem results from shrinking milk demand versus increasing milk production. The Walker administration made the problem worse, both by its misguided campaign to encourage more production and by bending over backwards to overlook the environmental effects of very large dairies.

A look at its website shows Organic Valley as a superb marketer. Here is how the coop introduces itself:

We started almost 30 years ago with a radical idea: A food company owned by the farmers who raise the food, instead of corporate executives only interested in the bottom line. A lot of people call us crazy. And we’re OK with that—because it’s totally working.

Founded in 1988, Organic Valley’s annual sales grew to $1.157 billion In 2018, according Wikipedia. It is also an innovator. Consider this July post from its Facebook page:

Parents, we’ve finally done it. Meet Ultra, the world’s first organic, ultra-filtered milk! Your little ones will give a thumbs up for taste, and you’ll love the 50% more protein, half the sugar, and no toxic pesticides.

Some years ago, a survey asked successful and unsuccessful entrepreneurs to give the most important factor for business success. The unsuccessful entrepreneurs gave a variety of answers–ranging from adequate capital to a good business plan to an enticing web site. The successful ones mostly gave a single answer: customers.

If customer focus is the most important thing for business success, much of the agricultural establishment indulges in anti-marketing. They argue that customers should accept bovine growth (BGH) hormones, antibiotics used to increase output, and genetically modified organisms (GMO’s). None of these make the product better from the customer viewpoint. Rather, they allow increased output, worsening the gap between supply and demand.

The original Foxconn contract suffered because it was driven by political motivations rather than well-thought-out business reasoning. From Foxconn’s viewpoint, the prime motivation appears to be heading off efforts by the Trump administration to restrict imports of Foxconn products. It also strengthened political ties to the then-Wisconsin governor (Scott Walker) and US House speaker (Paul Ryan). From the viewpoint of Donald Trump, Walker, and Ryan, it represented a job-creating win.

From the viewpoint of targeting distressed areas, however, the Foxconn project seemed to be in the wrong place, well away from the distressed areas in Southeast Wisconsin. This glaring defect might have been ameliorated with a well-designed plan for public transportation. But as plans have kept changing and shrinking, there is a growing mismatch between the jobs created and those needed.

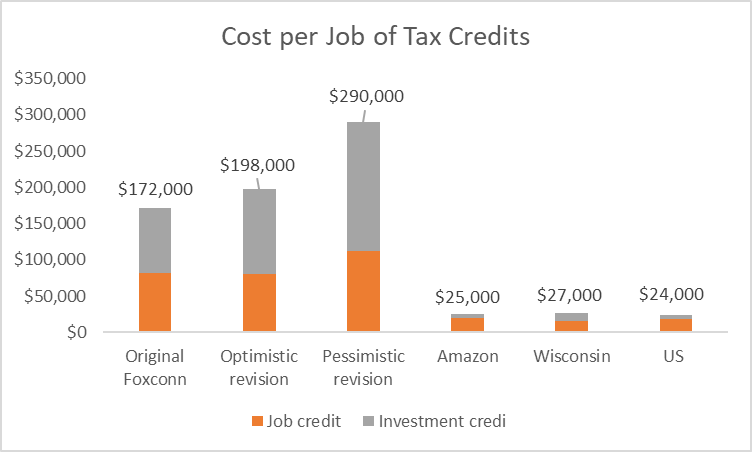

In a second recent report, Upjohn’s Bartik applied a variety of assumptions about what would happen at the Foxconn facility. The next graph shows his estimated cost per job under the original scenario and optimistic and pessimistic scenarios for the likely revisions of original proposal. The cost per job increases radically under the revisions, largely because the estimated number of jobs is radically reduced from the original 13,000 to 1,500 or 1,800. Also included for comparison is the average of the estimated cost per job of the Amazon proposals in New York and Virginia, as well as estimated “usual” Wisconsin and US tax credits.

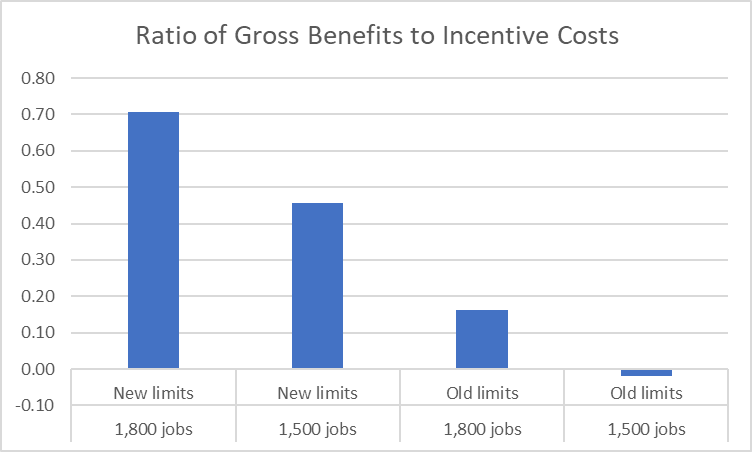

Bartik uses these values to calculate the ratio of the gross benefits to the cost of the tax incentives under four different outcomes: 1,500 versus 1,800 new jobs and whether the incentives have new lower annual and lifetime incentive limits. As can been seen in the next graph, the ratio is below one in all four scenarios, meaning that none of the scenarios offer net benefits to taxpayers.

His conclusion was not optimistic:

The most important conclusion of this analysis is that it is difficult to come up with plausible assumptions under which a revised Foxconn incentive contract, which offers similar credit rates to the original contract, has benefits exceeding costs. The incentives are so costly per job that it is hard to see how likely benefits will offset these costs.

In Wisconsin agriculture means dairy. Milk and other dairy products represent almost half of the value of Wisconsin agriculture compared to 10 percent nationally. Thus, Hughes’ experience with Organic Valley appears relevant to the crisis in Wisconsin family dairy farms and the rural county crisis. But does it prepare her to deal with the inner-city crisis in places like Milwaukee?

At first glance, the crisis in Wisconsin’s dairy farms would appear to have little in common with the crisis of urban neighborhoods left behind by the disappearance of manufacturing jobs. However, in both cases a willingness to reject past policies is the first step in developing an effective strategy.

More about the Foxconn Facility

- Foxconn Acquires 20 More Acres in Mount Pleasant, But For What? - Joe Schulz - Jan 7th, 2025

- Murphy’s Law: What Are Foxconn’s Employees Doing? - Bruce Murphy - Dec 17th, 2024

- With 1,114 Employees, Foxconn Earns $9 Million in Tax Credits - Joe Schulz - Dec 13th, 2024

- Mount Pleasant, Racine in Legal Battle Over Water After Foxconn Failure - Evan Casey - Sep 18th, 2024

- Biden Hails ‘Transformative’ Microsoft Project in Mount Pleasant - Sophie Bolich - May 8th, 2024

- Microsoft’s Wisconsin Data Center Now A $3.3 Billion Project - Jeramey Jannene - May 8th, 2024

- We Energies Will Spend $335 Million on Microsoft Development - Evan Casey - Mar 6th, 2024

- Foxconn Will Get State Subsidy For 2022 - Joe Schulz - Dec 11th, 2023

- Mount Pleasant Approves Microsoft Deal on Foxconn Land - Evan Casey - Nov 28th, 2023

- Mount Pleasant Deal With Microsoft Has No Public Subsidies - Evan Casey - Nov 14th, 2023

Read more about Foxconn Facility here

Data Wonk

-

The Imperial Legislature Is Shot Down

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

Counting the Lies By Trump

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Did Politics Affect Covid Deaths?

Jun 26th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jun 26th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson